5 strategies for swimming in rough water

In June 2002, I swam my first 28.5-mile Manhattan Island Marathon. The first half was a relative breeze, propelled up the East River by a flood tide and a tailwind, and enjoying relatively placid conditions in the narrow Harlem River. Conditions changed dramatically after we swam through Spuyten Duyvil and entered the broad Hudson River. A strong ebb tide butting heads with a 20-knot north wind plus wakes from heavy river traffic made it feel like swimming in a washing machine. For 30 minutes every stroke was a struggle – not only battered by waves, but pawing helplessly for a grip in the churning water.

But during the calm of a feeding stop, it occurred to me that while I might not be able to change external conditions, I might be able to reframe them. “It’s only water,” I told myself. “If I make myself long and ‘slippery,’ it should just wash over me, rather than knock me around.” Within minutes, I felt a ‘cocoon of calm’ descend, which I was able to sustain for the remaining 13 miles. The water did indeed feel as if it was moving around me rather than moving me around. The intense focus required to maintain that feeling for three hours produced such a pleasurable ‘flow state’ that I was almost sorry to see it end as the finish came into view.

The conventional wisdom on swimming in rougher water is that you must stroke faster, swing your arms higher and ‘punch through’ chop and swells. Well, punching through may work for the first, or fifth, or tenth wave you encounter, but how sustainable is it as a strategy when they keep coming, by the scores or hundreds? The water, after all, never tires or loses strength. But each wave saps yours a little more.

And ‘stroke faster’ is too simplistic a response for waves and chop that come in many varieties and from all directions. For each variation, a different stroke adjustment may bring the sense of control you seek. The Two Bridges Swim follows a down-and-back 1250-metre course between the FDR Bridge and the Walkway over the Hudson, at Poughkeepsie NY. The last time I swam it, we had the current with us as we swam south (the Hudson, a tidal river, flows both ways south of Troy NY) but a stiff northerly breeze sent waves against us. Unlike the confused chop of the 2002 MIMS, these waves came at more regular intervals.

Going south, I needed to make each stroke count to make headway against in-my-face waves. A few minutes of experimentation revealed that an up-tempo stroke with minimal pressure on my catch and two-beat kick provided the best sense of purchase and propulsion. Upon turning north, I ‘surfed’ the now-following waves – maximising the distance I covered with each stroke by moderating my tempo and using a firmer catch, strong hip drive and drawing more power from a well-synchronised two-beat kick.

And just as swimming up- and down-river required two ways of stroking, swimming on a more complicated course may require even more adaptability. The Big Shoulders Race, a 5k on Lake Michigan in Chicago, features two loops on a triangular course. Both times I’ve swum it the Windy City lived up to its name. Waves which battered us from the side on the first leg, and smacked us from the front on the middle leg, made the third leg a pleasure. Each time we rounded a buoy, I used a slightly different stroke – a total of six technique tweaks in the course of 90 minutes. The takeaway? Thoughtful experimentation and adaptation are likely to be more effective – and more enjoyable – than heedless churning or brute force.

FIVE STRATEGIES FOR WHEN CONDITIONS GET TOUGH

These five strategies have greatly increased the control and satisfaction I experience when wind and waves kick up. Three are technique-oriented. One is training-oriented. The fifth targets your mental approach. You’ll need hours of pool practice to gain familiarity and consistency. Then, when the water turns ‘sporty,’ you’ll be able to continue making subtle adjustments until you find the approach that works best.

1. Create a sleek and stable ‘vessel’

Even in the calm of a pool, human swimmers typically waste more than 95 per cent of energy by moving around in water and moving the water around, rather than moving through water. Amidst waves and chop, we move around even more. Three focal points will help stabilise you in rougher water:

Wide tracks: Enter then extend beneath the surface on a ‘track’ directly forward of your shoulder. Press back on the same wide track. Avoid your body’s centre-line. Wide tracks act like outriggers, helping you resist being rocked or rolled by swells from the side.

Swim ‘flat’: Consciously control hip rotation; avoid ‘stacking’ hips or shoulders. This improves core stability, reducing the tendency of legs to splay and allowing a more stable hold on moving (or still) water, as you begin the stroke.

‘Rag doll’: During recovery, consciously turn off all muscles below the elbow, so your arm hangs like a rag doll as you approach entry. When waves hit a stiff arm, the shock is transmitted to your body. A relaxed arm absorbs the impact, preserving stability in your core.

2. Practise a ‘patient’ and feather-light catch

In challenging conditions, my mantra is: “The rougher the water; the calmer and quieter I must be.” A common frustration in chop is suddenly losing your grip as you begin to stroke, like a car spinning its wheels. To avoid this, take a nanosecond longer beginning each stroke, and press as lightly as possible. Practise in the pool to discover how much better you convert rearward pressure into forward motion when you press more gently – and more precisely.

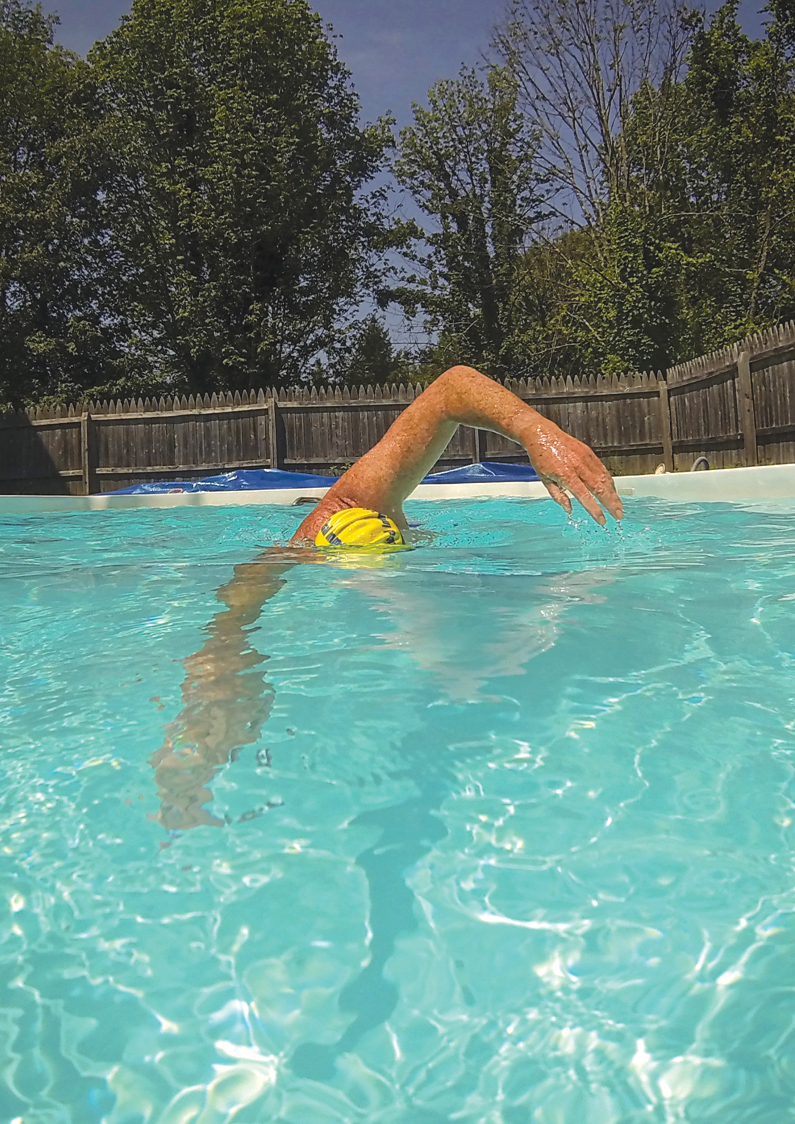

3. Breathe low

In the 2006 World Masters Open Water Championship in the churning waters of San Francisco Bay I moved smoothly through a pack of about 10 swimmers – all of whom lifted and whipped their heads around on each breath. This so thoroughly disturbed their ability to stroke effectively that they all seemed to be swimming in place. In contrast, I breathed with body roll and kept my head aligned with my spine. Remember this: in even the roughest water, there will always be air at the tip of your shoulder. In swells and chop, keep your head low (rest it on the water) and let your chin simply follow your shoulder to air. Well-controlled head movement greatly increases the control you feel in every other part of your stroke

4. Develop gears

Develop a more adaptable stroke – one in which you can vary stroke length, tempo and pressure – in pool practise by doing the following:

Use all four strokes per length (SPL) in your personal (height-indexed) Green Zone of efficient stroke count per 25m (see chart below). Strive to swim repeats with equal smoothness and control at all four counts.

Explore the full range of tempos you can swim at each of your counts.

Practise swimming each stroke count at pressure ranging from featherlight to moderate to firm. Can you increase stroke pressure slightly on each repeat yet still strike the wall in the same count?

Doing these exercises in pool practice will give you command over subtle adjustments to adapt to a wide range of conditions in ‘sporty’ water.

Practise a patient and feather-light catch

5. Be observant

Perhaps the most important skill of all is simply to keep your wits about you, so you can respond opportunistically, rather than reactively, to challenging conditions. If conditions get wilder, strive to be calmer. In the midst of a pack of churning swimmers, strive to be the ‘quiet centre.’ When you observe those around you lifting or whipping their heads, let that be a reminder to keep yours low and connected to body movement. Or try to keep your stroke a little slower – and freer of bubbles – than others swimming nearby.