Surfacing an Aquatic Diaspora

Contrary to the enduring myth, Africans have always been expert swimmers. By Elaine K Howley

Kevin Dawson grew up a surfer in San Diego. While there’s nothing terribly unusual about a young man from Southern California taking full advantage of the waves in one of the sport’s North American meccas, for Dawson, he was always aware that he was different from most of the other surfers he saw perched atop their boards, waiting patiently for the

next swell.

He’s Black. And, of course, there’s a long-standing stereotype that Black people don’t swim or surf. This false notion grew out of the legacy of slavery and was exacerbated during the Jim Crow era – a time of apartheid in America, which officially lasted until the middle of the 20th century but casts long shadows today. The belief that Blacks couldn’t swim became a pervasive, self-fulfilling belief for many, and the idea lingers still like the stench of low tide.

A Personal History

For many Black people, the water seems a foreign, daunting place. Denied access because of racist laws and the relentless, systemic disadvantaging of people of colour in the Western World, over time, many Black people lost their easy connection with the water.

For Dawson, though, the water is a soothing place. “It’s connecting back to nature in this really surreal, blissful environment that lets you defy gravity, and it’s so unlike being on land.”

Dawson has always been in tune with the water. “I learned to swim at a mommy-and-me class at the YMCA when I was about three months old, and I grew up swimming,” he says. He started surfing at about age 11 and was competitive. “I was sponsored as a teenager,” he recalls. He also free-dives, and so has spent a substantial portion of his life in the water. “I was just always in the water,” he says.

But in his teenage years, he came to realise that there weren’t a lot of other swimmers that looked like him. “As a kid back in the ’70s, there weren’t very many Black swimmers. When I was swimming competitively, I rarely saw a Black swimmer. And when I was surfing, I rarely saw Black people. There were about five other Black surfers that I knew of.”

He was something of an anomaly. “I knew there were these perceptions of Black people not swimming and not being involved in the water – these stereotypes and myths.” But his personal connection to the water was undeniable.

As he came to discover later, his affinity for riding the waves is far less unusual than many people believe.

Deconstructing a False Narrative

Dawson started his career in academia studying marine biology in college, “but the problem was, I was really bad at math, and that became a hang-up,” he says. But he soon found that reading about the past captured his attention and he gravitated towards the field of history.

In studying the Civil War as an undergraduate, he “came across more and more accounts of enslaved people using dugout canoes or other boats or just swimming to freedom, and it made me realise that there was this whole other field of scholarship that hadn’t been studied.”

So, he began digging into it. “I increasingly became drawn into finding the sources that documented African-descended people both in Africa and the Americas who were engaged in aquatics.” The results were eye-opening. Africans had once ruled the waves in ways it may be difficult to fully appreciate today.

Despite the storyline that has been perpetuated for so long, Blacks do swim, and it used to be that their skills far exceeded those of the average white European – after the fall of the Roman Empire, western Europe effectively forgot how to swim.

But Africans carried on plying the water for survival, commerce and, indeed, fun. Writing in 1455, Venetian merchant-adventurer Alvise da Cadamosto noted that swimmers he observed in the Senegal River “are the most expert swimmers in the world.”

To prove the point, he asked several swimmers to carry a letter back to his ship anchored a reported three miles off shore in stormy conditions. Two accepted the challenge, which Cadamosto felt was impossible. But about an hour later, one of the swimmers returned with a reply from someone aboard the ship. “This to me was a marvelous action, and I concluded that these coast negroes are indeed the finest swimmers in the world,” he wrote.

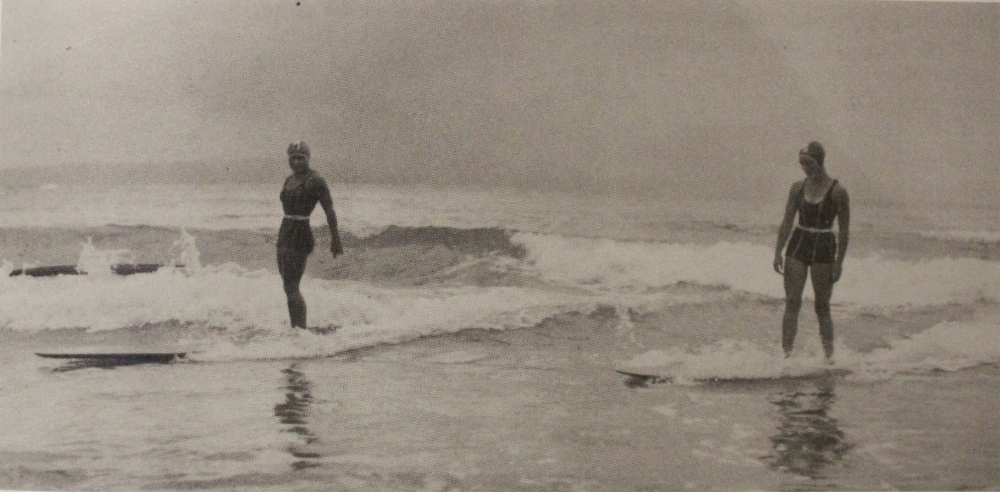

Stories such as these abound in the annals of history if you know where to look, and as Dawson turned over scholarly stones, he learned that swimming, surfing, and the construction and use of boats “are things Africans have been doing for thousands of years, both in Africa and what becomes the United States. And to be able to make those connections was really rewarding, and in a way, kind of spiritual.”

No longer was he the rare Black man in a sea of white surfers. Now, he could take his place in a lengthy aquatic heritage. Though the story of Black people swimming, surfing and plying the water for sport and survival had been hidden for generations because of fear and bias, there was perhaps an innate reason Dawson felt so at home in the water himself. The water, it seemed, is in his blood.”

Swimming While Black

Throughout his research, Dawson has learned of dozens of startling incidents of Africans leveraging their aquatic skills in various ways, both in Africa and as enslaved persons in the New World. Two in particular have stood out for him, though he recounts dozens more such incidents in his acclaimed 2018 book Undercurrents of Power: Aquatic Culture in the African Diaspora.

The book won the 2019 Harriet Tubman Prize from the Lapidus Center for the Historical Analysis of Transatlantic Slavery at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, part of the New York Public Library. The prize is bestowed on the best US-published non-fiction book on the slave trade, slavery, and anti-slavery in the Atlantic World.

In his work, which the award’s jury called “generative” because it “opens up new ways of studying Atlantic History and the African diaspora,” Dawson has uncovered some extraordinary incidents of Black swimmers, divers, surfers, and boat handlers.

The first such story involves a cohort of about 20 Black women swimming, doing laundry, and socialising in the Turtle Crawl River in Jamaica in 1823. The nude women were alone until a group of white men happened upon them.

Dawson writes in Undercurrents of Power that the women knew exactly how to respond to the potential threat that these men posed in that moment, as reported by one of the men, Cynric Williams.

“When the men were discovered, the women ‘on shore dashed into the water…. When they were, according to their own notions, far enough from our masculine gaze, they emerged one by one, popping their heads and shewing their ivory mouths as they laughed and made fun of me.’ On land, they had reason to fear white sexual assault. Swimming abilities afforded protection unparalleled ashore.”

The water – or more precisely the women’s facility and comfort in that medium where the white men who couldn’t swim wouldn’t follow – provided protection from these would-be predators.

“Water was a sanctuary from unwanted sexual advances,” Dawson writes, and even afforded the women the physical barrier they needed to not only take back control of their bodies in that interaction, but to also torment the men, à la the Sirens of Greek mythology. If the men dared enter the water to gratify their sexual urges, they would likely drown.

“The women understood that the water provided them with this safe space where they could actually be nude and also mock men who wanted to rape them. I think that’s a really telling example of the power of water,” he says.

Another significant entry Dawson uncovered dates back to July 1545 with the sinking of King Henry the VIII’s flagship the Mary Rose in the Solent by a French invasion fleet. Despite having the latest tools, such as diving bells, “the English were unable to refloat or salvage the Mary Rose,” Dawson explains.

So they cast about for help in retrieving the goods that sunk along with the ship. They hired a Venetian, named Petri Paulo Corsi, but he couldn’t salvage it either. Giving up on the modern tech and turning to skilled divers for help instead, Corsi hired eight Africans to salvage the wreck of the Mary Rose.

These men were very successful in short order. “Not only do they salvage the Mary Rose, but they end up going on to salvage other English ships,” Dawson says, which led to a degree of esteem in the maritime community at Portsmouth.

“They’re not treated like African men. They weren’t enslaved – they’d been hired from Africa,” likely from Senegal, Dawson says. After salvaging several ships off the coast of England, they were hired to retrieve goods from sunken vessels in the Mediterranean as well.

“So they end up going all around the Atlantic working as skilled laborers. And their race is not at all subjecting them.” That afforded them certain professional courtesies not extended to enslaved people, who made up the majority of people of colour in England at the time. They stayed at the Dolphin Inn in Southampton (which still operates as a pub today) where “they were given meat, which was a luxury,” Dawson says. This is a clear sign that they held social power during a lean time when those deemed as lower class weren’t afforded extravagances such as fresh meat.

“The important thing is to understand the social dynamics,” Dawson says. Noblemen would come to the tavern where these men from Africa were staying, and some of them came specifically to hire these men to salvage their sunken ships.

In addition, inns of that era often operated as brothels, and while “the sources don’t speak to it, these African men would have also, presumably, been having sex with English prostitutes,” Dawson says.

All of these interactions “would have gone against these notions of race and racial subjugation. These men are interacting with noblemen, and having sex with white prostitutes. It’s really kind of eye-opening how these men’s skills enable them to defy all these ideas of social status and class at a time when race and slavery were being used to subjugate Africans.”

Reclaiming an Aquatic Heritage

History, it’s often said, is written by the victors, and the real story is sometimes obscured by the writer’s own biases.

White slave holders who dreaded the water and couldn’t swim projected their own fears onto Black people they owned. Constructing a narrative that Blacks don’t or can’t swim caught on over time as a means of negating a power African-descended people held over their captors.

In addition, because many African-descended people in the New World did possess swimming skills – which they sometimes were able to deploy in escaping or resisting their captors – squelching enslaved people’s access to the water was an effective means of controlling them and preventing ‘property’ loss.

But there’s nothing about the water itself that wants to exclude Black bodies. Indeed, they once were the best swimmers, surfers, and sailors to be found on the planet.

Through his research uncovering the aquatic roots of his ancestors, Dawson hopes that other Black swimmers will realise that they belong in the water, too, just as much as anyone else. “I had taken solace in swimming and surfing,” and to have the knowledge now that “I’m able to make connections with ancestors,” has been powerful.

“I think that my research is showing that [the ideas around Blacks not swimming] are myths and stereotypes. Black people can excel in the water.”

Getting this message out – particularly to parents who may be fearful of encouraging their children to swim because they themselves cannot – is important work that not only can result in reduced fatalities, but increased joy and overall health and wellbeing for a substantial group of people who have been denied access to the joys of water for far too long.

Slowly, access to aquatics and representation of people of colour in waterscapes is improving. “I do see more and more Black people swimming and surfing,” Dawson says, a rewarding outcome that he’s helped bring about through his scholarship and his volunteer work with organisations that encourage Black kids to swim, surf and otherwise connect with their aquatic heritage.

With his research and his own ongoing love affair with open water, Dawson is helping to reinstate an erased history and dispel the myths surrounding Black swimmers. He’s returning a right to people who’ve been denied access to a place of power, comfort and healing for generations.