Poor pacing produces piss poor performance

How many times in a swimming event have you tried to “go out hard and hang on”?

It sounds like a compelling strategy. If you can get into a good position at the beginning of the race that should motivate you to keep trying. Seeing yourself swimming shoulder to shoulder with the race leaders will surely give you a confidence boost that will carry you through to the end, won’t it?

We’ve previously argued that it’s actually a very ineffective strategy (for example, see Don’t Smash It). It’s also something that Paul Newsome at Swim Smooth has highlighted many times in his blogs and in articles he’s written for H2Open.

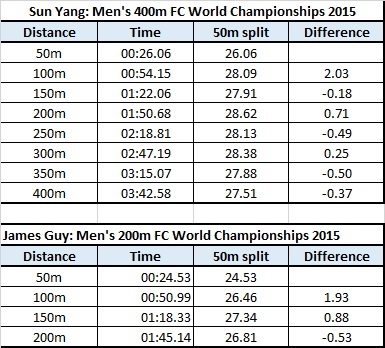

If “go out hard and hang on” was a good strategy, then why don’t world class swimmers do it? The table below shows the splits for Sun Yang and James Guy, winners of the men’s 400m and 200m freestyle at last year’s World Championships. In the 200m in particular, you can see how Guy’s pacing enabled him to swim a strong last 50m, overtake Sun Yang, and snatch victory by 0.06s. Notice how even (apart from the first 50m which is faster due to the dive start) these swimmers’ splits are for each 50m of the race. In the 400m, Sun Yang is faster in the final 100m than at any other point of the swim (except again for the first 50m).

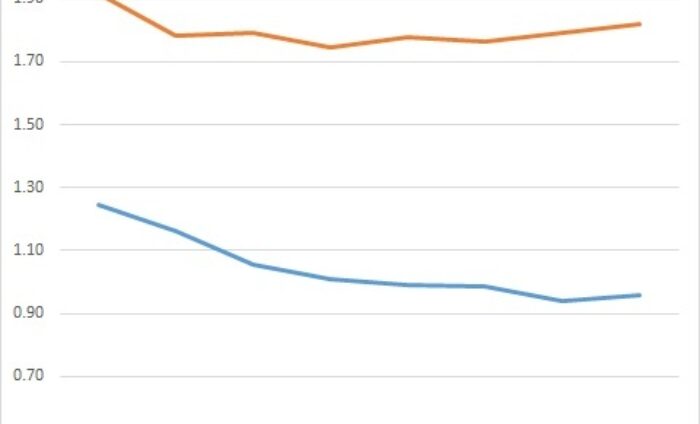

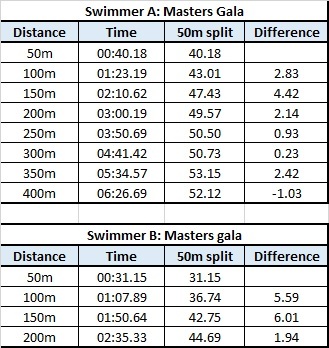

In contrast, take a look at these splits from a recent masters swimming gala. These are real times from real swimmers although we’re hiding their identity under the labels Swimmer A (400m) and Swimmer B (200m). Notice how much these swimmers slow down through the swim (see also the chart above comparing Swimmer A’s speed with Sun Yang’s). Swimmer B was in fact leading his age-group by around half a second at the half-way mark but ended up more than 15 seconds behind the eventual winner. For both of these swimmers, the final part of the race was significantly slower than the first part.

The evidence that even-pacing is the best strategy for the fastest overall time is compelling. A lot of swimmers say they agree, but judging by their swim splits, they don’t do it. The examples we’ve chosen are at the extreme end but if you look through the results of almost any masters gala you’ll see the majority start fast and finish slow. The situation is possibly even worse in open water events, although we don’t have the pacing data to prove it. It’s not a race to the first turn buoy, although many people seem to think it is!

So why is this? One reason is that swimmers think it’s not the best strategy for them personally. They say things like, “I need to start fast to get my heart rate up”, “I’m naturally a sprinter, so I need to make the most of my advantages and get out fast” or “I don’t have the fitness to sustain my pace.”

If that’s you, we suspect no amount of logic or examples will convince you otherwise.

However, the other reason however is that perfect pacing is actually really hard. You may want to do it, but you can’t. It requires your brain to be totally in tune with your body so that you feel exactly what the right pace is. And that ‘perfect pace’ is different for each distance. James Guy’s pace per 50m on the first 200m of his 400m race was an average of 1.37 seconds slower than on his 200m. How did he dial in to exactly the right pace for those two swims? If you race in open water you need to be able to sense what the optimum pace is to sustain you for a mile, for 5km, 10km or longer.

Telling you to start more slowly would help, but it’s not really about swimming slowly, it’s about swimming with control. You need to learn what it feels like to swim at your optimum 400m pace (or 1 mile or 5km pace) both when you’re fresh at the beginning of the swim, half way through when fatigue is beginning to set in and at the end when you’re busting a gut to swim the same speed you thought was easy just a few minutes previously.

How do you do that? Practice, obviously, but it needs to be very specific practice where you stay mindful of your pace throughout. A pace clock is your friend here but a watch will also do and a Tempo Trainer is a useful tool (see p.68 of our Feb/Mar 2016 issue for an article on this). Say you’re doing a set of 100s. Set yourself the objective of swimming every one at the same speed. Another time, try swimming each of those 100s two seconds slower than you did the previous time, or a second faster, or try starting slowly and swimming each one slightly faster than the previous. Play around with different times and distances to see what happens. Can you maintain the pace if you mix in some 200m swims with your 100s for example?

Every time you complete an interval, check how long it’s taken you. If you can, take a sneaky look at the pace clock while you’re swimming to see how you’re doing at half way. This isn’t about trying to swim faster, it’s about learning how it feels to swim at different speeds and this will be a massive help to you when you come to race. Set your own pace rather than trying to match that of other swimmers.

Elite swimmers are not just faster than us, they pace their efforts much better. It’s not just a question of fitness (if you’re unfit it makes even more sense to start slowly), it’s their ability to feel and control how fast they are going. Even if you can’t learn to swim as fast as Sun Yang and James Guy you should be able to get your pacing more like theirs. Slowing down by five seconds at the beginning of a race may initially feel wrong, but if it saves you 10 seconds at the end then it’s worth it.

Also, swimming a well-paced race feels so much better than blasting the first part and then battling through the rest.

So next time you line up for a swimming event (either in the pool or open water), remember the six ‘P’s: Poor Pacing Produces Piss Poor Performance.

Chart shows the average swim speed for each portion of the race for Sun Yang and Swimmer A