Farallon Islands to California: the world’s toughest ocean swim

Only five people have managed to swim from the storied Farallon Islands to mainland California. By Elaine K Howley

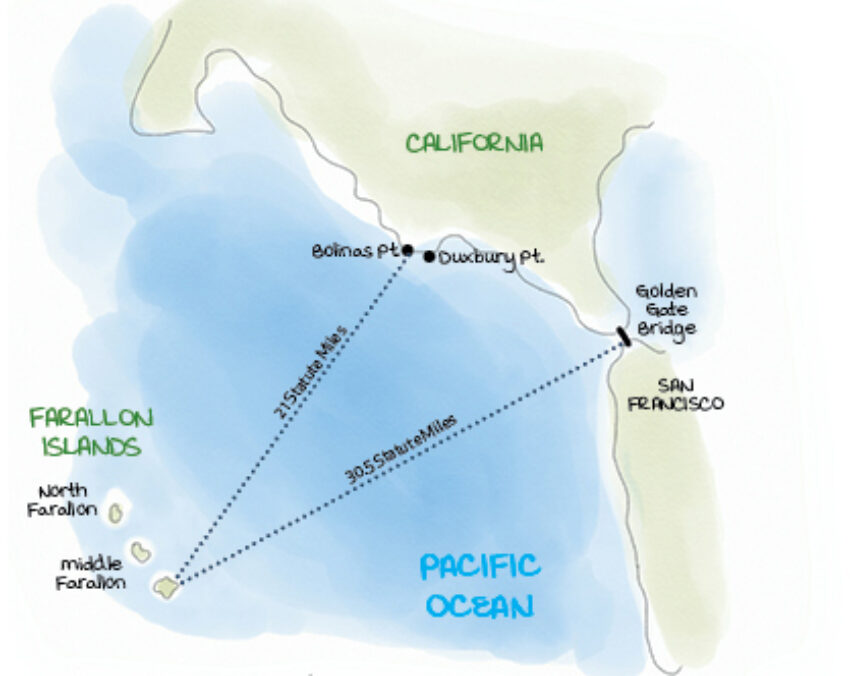

Shortly after finishing his 2014 swim from the Farallon Islands to Muir Beach in Marin County, California, north of San Francisco, Craig Lenning, now 38, of Denver, Colorado, gave an interview to a local news station. The 41.3-kilometre (25.6-mile) swim was big news in the San Francisco Bay area, as Lenning was the first swimmer in 47 years to complete it. In the interview, Lenning said: “This was a tough one. This was the biggest one I’ve ever done, just ‘cause the mystique of it, the cold, the magical islands off the coast…”

In his 1974 tome, Wind Waves and Sunburn: A Brief History of Marathon Swimming, historian Conrad Wennerberg also listed the Farallon Islands to Mainland swim as one of “the toughest swims in the world,” on par with a double English Channel swim and a crossing of the frigid Strait of Juan de Fuca. What makes it so tough is a combination of very cold water (typically 10 to 15 degrees Celsius), potentially dangerous sea life and strong tidal flows and currents.

Although they lie a mere 30 miles southwest of the bustling metropolis of San Francisco, the Farallon Islands are a remote, desolate smattering of jagged rock islands moored in a foggy expanse of the Pacific Ocean teeming with life. The islands are now a protected marine sanctuary with strict regulations prohibiting humans from accessing, but sailors in the 1850s dubbed them the Devil’s Teeth because of their proclivity for snaring and wrecking passing ships. The Farallons also mark the westernmost point of the so-called Red Triangle, a loosely-defined area from Monterey Bay about 70 miles south of San Francisco to Bodega Bay 120 miles to the north that’s home to significant great white shark activity.

According to a 1987 article in Surfer magazine, shark encounters occur at a rate of one per “1.9 hours [at] the Farallon Islands, where conventional wisdom dictates entering the water is suicide.” While this might be a case of writerly hyperbole, the fact remains, roughly 11% of unprovoked shark attacks worldwide have transpired in the Red Triangle, according to the International Shark Attack File at the University of Florida. This is largely the result of people being in the wrong place at the wrong time; unprovoked shark attacks are nearly always a case of mistaken identity. The shark thinks a person is a seal-like snack and takes a test bite. Depending on where the person has been bitten, that exploratory taste could be deadly.

The good news is, the Pacific population of great white sharks follow a fairly predictable migration cycle, which sees them spending the winter out near the Hawaiian Islands. Between April and July, they head toward the Southern California coast to breed. Then, between August and September, they congregate around the Farallon Islands, drawn by the robust population of seals that also call these rocks home. The Farallons are a rich feeding ground where the sharks can top up their reserves before heading back to Hawaii for the winter. The odd surfer or triathlete venturing into the water looking a bit too much like lunch can find him or herself at the business end of a great white, and the myth of sharks being voracious man-eaters is perpetuated.

Therefore, plunging into the water off the Farallons and endeavouring to swim more than two dozen miles back to the mainland is not a risk-free activity, and in an effort to reduce his exposure to the “man in the gray suit,” as he calls great whites, Lenning opted to swim in April, while the water was still cold but before most of the population had returned for the summer. A burly, experienced cold-water swimmer fresh off a relay across the Bering Strait, Lenning felt more confident facing 10-degree C water than a 15-foot fish with 300 teeth.

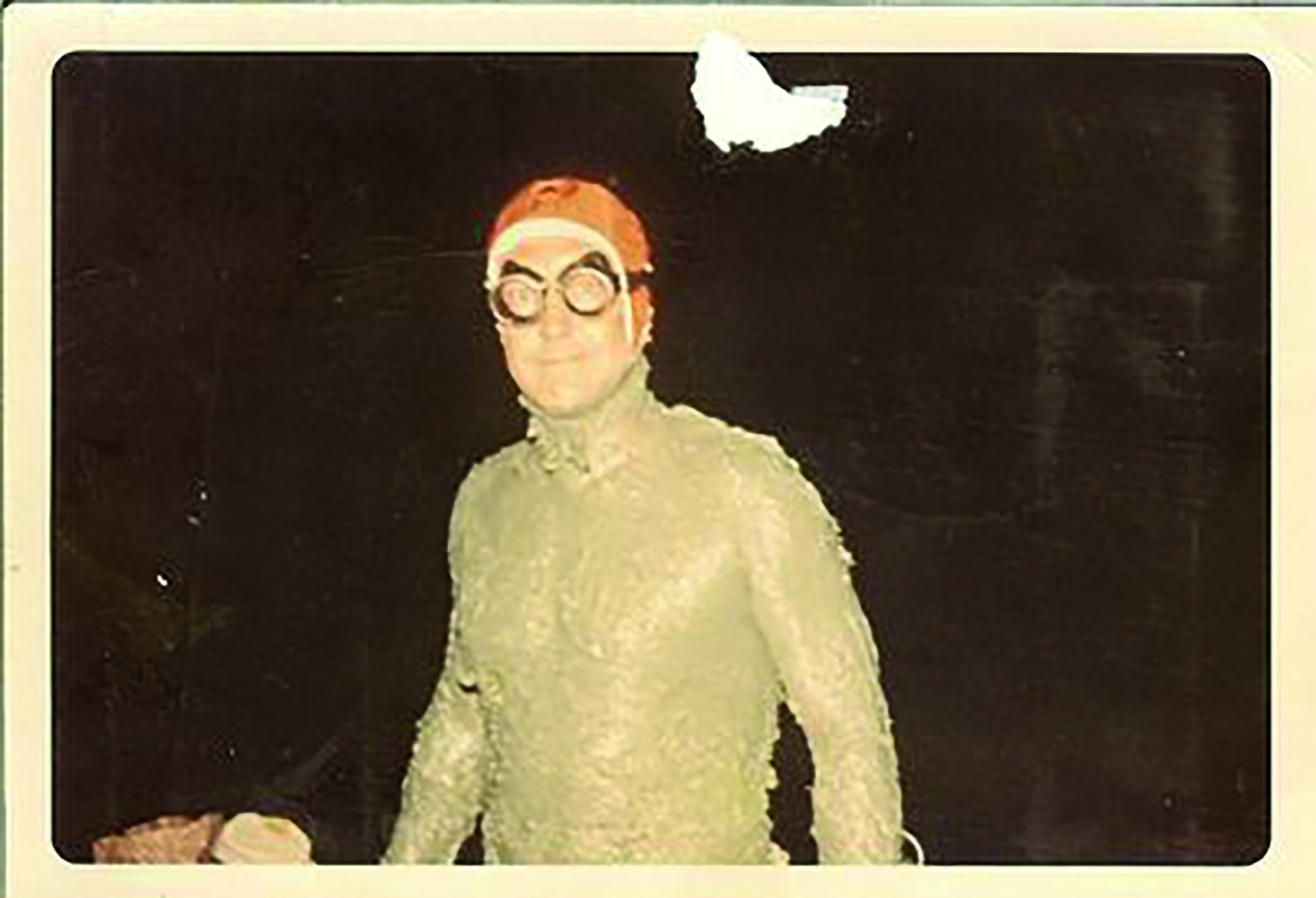

Stewart Evans tells the press about his swim

On the Shoulders of Giants

Though Lenning’s swim was impressive, he was merely following in the footsteps of two towering figures in the history of marathon swimming.

On 28 August 1967, one of marathon swimming’s greatest prizes was claimed. That’s the day Lieutenant Colonel Stewart Evans, a 43-year-old army signal officer, became the first person to swim from the Farallon Islands to mainland California. He landed near Bolinas, California, about 25 miles north of San Francisco.

Reel-to-reel footage of the swim shows that as he neared the beach, Evans stood shakily, steadied himself, then lightly jogged ashore in broad daylight cheered on by three swimmers who’d joined him in the water for the last little bit. He was greeted at water’s edge by a crowd 100-strong, complete with a handful of local reporters. One thrust a microphone in his face and asked if he ever doubted he’d make it. Evans explained that severe pain in his left shoulder was the only thing that threatened the swim. “We heard there was a shark out there a while ago. Did you see one?” another reporter asks. “No, I didn’t see much of anything except the boat I was following,” Evans replied with a tone of water-weariness.

The footage is the stuff of swimming mythology, and Evans’s daughter, Michelle Evans-Chase, says the swim was a special aspect of her family’s life when she was a kid. She remembers watching that footage and frequently seeing photos from the swim. And it wasn’t just about the swim itself; she says her father’s accomplishments and love of swimming was an inspiration in other parts of her life, too. For example, hearing how he answered that reporter’s question “shaped my understanding of men,” she says. “I thought that was really cool,” that he admitted that there was a time when he wasn’t sure he could finish the swim. “That it was OK to say, ‘yeah. I was scared,’ or that, ‘it was hard and I thought about quitting.’ To admit those things was not weak.”

In addition to being the first to cross from the Farallons to mainland California, Evans also swam the Catalina Channel and the Salton Sea. “He swam lots of large bodies of water. It’s just what he did,” Evans-Chase says. And he did lots more long-distance swimming “for the love of it,” she says, rather than for any kind of kudos. In fact, he turned down an invitation to be inducted into the International Marathon Swimming Hall of Fame after becoming the first Farallons finisher, Evans-Chase says. He just wasn’t into the fanfare.

Evans entered the Army at the tail end of World War II and also served in the Korean War and the Vietnam War. “When he was stationed in Korea, he did long swims there and long swims out of the Dolphin Club [a long-standing swimming and rowing club based in Aquatic Park, San Francisco]. I don’t know what got his attention at the Farallons,” Evans-Chase says, but his interest was likely piqued by the several years of big-name swimmers unsuccessfully making attempts. These would-be challengers included Danish-born American open water legend Greta Andersen and fellow World Professional Marathon Swimming Federation competitor Myra Thompson. Wennerberg notes that by spring 1966, 17 unsuccessful attempts had been made from the Farallons by various well-known swimmers, with a handful more to come before Evans stepped into the water the following summer.

To become the first successful swimmer, Evans – who was planning the swim long before the internet and its precise tide charts and modelling software could help – reached out to local coastguard officers for assistance and studied paper charts. His nutritional plan was equally low-tech: at the finish he told reporters he’d subsisted on lemon Jell-O and 7-Up.

In becoming the first to swim from the Farallons, Evans set a precedent and proved it could be done. He was quickly followed in success by the legendary Ted Erikson, a larger-than-life figure from the heyday of marathon swimming who’d already logged two unsuccessful attempts to swim from the Farallons to the Golden Gate Bridge. In the first attempt, he was pulled out of the water after some 17 hours, and members of his crew reportedly thought he’d died. He had not, but was so hypothermic, he might have been on the verge.

Undeterred and focused on the original goal at the Golden Gate Bridge, on 16 September 1967, Erikson made his way from the Farallons to the bridge in what would be his final long-distance swim. In an account of the swim published in 2013 on the Daily News of Open Water Swimming, Erikson writes there was much ballyhoo upon his arrival at the bridge. “Rocket pyrotechnics were set off as we went under the Golden Gate in a wonderful firework display (compliments of Brigadier General MF Casey, USAF Commander of the 80th Military Airlift Wing). An enthusiastic crowd at the bridge railing dropped flares from the bridge. The coastguard thought ill of the jubilation and issued a radio alert for mariners to disregard the flares.”

Stewart Evans

“A Lark”

After completing the swim, during which water temperatures registered a balmy-for-the-Farallons 55 to 60 degrees F, (12.7 to 15.5 degrees C) Erikson told a San Francisco Examiner reporter that his “time was respectable… water conditions unbelievable.” He thought his record might “stand forever,” and described the swim as “a lark.”

His record nearly did stand forever, in sporting terms: 47 years. It was only eclipsed in 2014 by Joe Locke of Mill Valley, California, by 40 minutes. The then-45-year-old swimmer became the fourth person to make the swim and the first since Erikson to land at the Golden Gate Bridge. The fifth and so-far final solo swimmer to make the arduous trek was also the first woman to add her name to this rather exclusive list. Oceans Seven finisher Kim Chambers, a New Zealander living in San Francisco, completed her Farallons to Golden Gate Bridge swim on 8 August 2015 in 17 hours, 12 minutes.

Although this spate of three modern solo swimmers might be a small resurgence, it’s an uptick that likely owes its existence to the efforts of Vito Bialla and Farallon Islands Swimming Federation co-founder Phil Cutti. The pair established the organising body as an off-shoot of their activities with the Night Train Swimmers in 2011, and Bialla has escorted all the solo swimmers and relays in the modern era.

Bialla says his phone is not exactly ringing off the hook with new inquiries, but the swim remains a substantial challenge for worthy contenders. “It’s dangerous not just because of sharks. It’s a long swim. It’s like the Badwater ultra-marathon run – not everyone wants to do it. The people who have done it are legends in swimming history. It’s a monumental achievement,” he says.

Information on solo and relay swims is available on the Farallon Islands Swimming Federation’s website.