Risk, benefit and perception in cold water swimming

And what is the optimum length of time to swim?

Let’s be clear from the outset: science has not given us an equation to work out the optimum amount of time to swim in cold water. Nor, I suspect, will it ever. There are too many variables, and too much individual variation. Plus, you have to factor in your subjective experience.

This doesn’t mean we can’t think about cold water exposure in a sensible and reasoned way, using what science and experience tell us.

The key factors to consider are the risks, the benefits and how it feels. The latter comes with a caveat, as we will see later. A fourth factor is the question about what you want to get out of cold water swimming. Are you doing it for pleasure and your general health and wellbeing or are you exploring and testing your physical limits?

Starting with risk, we know the biggest challenge in the first couple of minutes is cold water shock. With prolonged exposure, our risk of swim failure and hypothermia increases. The exact timescales and magnitude of the risk depend on a range of factors including our habituation, the conditions, our fitness and body type.

The current thinking is that the benefits from cold water swimming mostly accrue within the first few minutes. As we stay in longer, it’s likely that the increased stress caused by the body cooling diminishes the benefits, especially in extremely cold water where it’s not possible to stay in long enough for a training fitness effect.

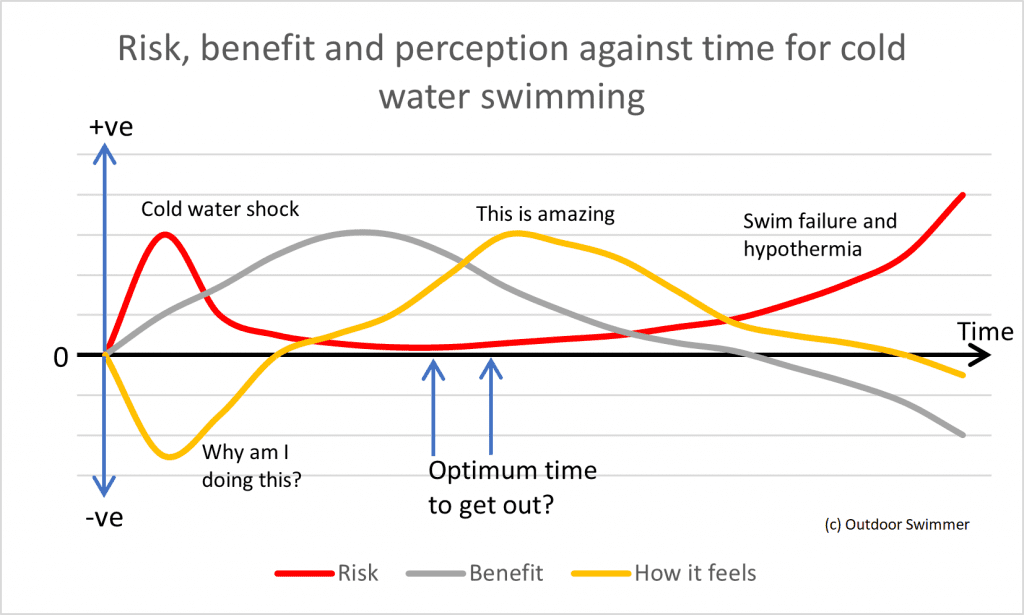

Next, consider how it feels, and surely everyone is different here. For me, at the beginning of every cold swim, I have a brief period of extreme unpleasantness, tipping into pain as it gets very cold. This is followed by a longer spell of feeling amazing, which tails off as the cold seeps in. The length of this cycle is dependent mostly on the water temperature but is also influenced by what I’ve eaten, how tired I am and other random factors. As a bit of fun, and a thinking tool, I’ve plotted these factors onto a chart. It makes it look scientific but it’s not. I’ve deliberately not put in any numbers or time scale. The horizontal axis represents time, while the vertical axis is an arbitrary scale. The red line shows risk, the grey line is the benefit while the yellow line represents how it feels.

Too much of a good thing

While everyone’s lines will be different, risk will always increase with prolonged exposure. Nobody can escape hypothermia forever. And while a little bit of stress from cold water exposure seems to be good for us, too much isn’t. In general, your optimum time for swimming should therefore be the amount of time that minimises the risks, maximises the benefits and puts you into the feel-good zone.

However, in some circumstances, you may want to extend your time in the water. The main reason for doing so would be during or in preparation for a cold water swimming challenge. This type of swimming is an extreme sport and should be approached as such with proper planning and preparation, and with the full agreement and support of the people around you. Your fellow swimmers and/or venue lifeguards are the ones who will have help if you get into difficulties, so make sure they are prepared for this and comfortable with it. You should be aware that you may reduce the benefits and you certainly increase the risks if you start pushing the limits of how long you stay in cold water. I expect you’ll be pushing yourself into territory where it doesn’t feel so good too. You’ll have to decide for yourself if that’s where you want to take your cold water swimming.

Finally, for those of you who aren’t pushing your limits, remember that the feel-good phase could well extend past the time of peak benefits and into the period when risks are increasing rapidly. Please keep this in mind when swimming outdoors this winter and control your time in the water accordingly. Keep it fun and safe.