The River Thames: a wet, winding history

The River Thames has long lured swimmers to her banks.

For millennia, people have built settlements along the sinuous curves of the River Thames, which runs across the chalky landscape of southern England from Gloucestershire eastward past Oxford (where it’s called the River Isis) through the Chiltern Hills and on to London. After a 215-mile journey across the country, it drains into the North Sea.

Known to the ancient Romans as the Tamesis, it’s believed the name may mean dark, referring perhaps to the water’s murky colour. Spelled Tamisiam on the Magna Carta, some Victorian-era cartographers posited that the river was more accurately called the Isis from its source to Dorchester-on-Thames where it connects with the Thame (a tributary) and becomes the Thame-Isis, which contracts neatly to the word we know today: Thames. No matter what you call it, this vital river cuts through so many aspects of British history, not least of which is its rich record of long-distance swimming.

Luring the Literati

The cooling waters of the River Thames have long beckoned swimmers from all walks of life. From overheated East Enders looking for relief on a steamy summer day to heads of state and a vast number of ambitious swimmers hoping to make a name for themselves, the winding waters have long offered a blank page for oodles of swimming stories down the ages. Certainly, the intellectual set – poets, authors, philosophers and statesmen – haven’t been immune to the lure of the Thames.

In her book “Downstream: A History and Celebration of Swimming the River Thames,” Caitlin Davies reports that author Jonathan Swift enjoyed swimming in the Thames near Chelsea regularly as a way to cool off in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Just like us, he apparently didn’t enjoy the boats that would occasionally interfere with his skinny-dipping, writing to his friend Esther Johnson that at least one swim resulted in “much vexation… for I was every moment disturbed by boats, rot them.”

In 1726, one of America’s founding fathers – Benjamin Franklin – reportedly relished a three-and-a-half-mile swim from Chelsea to Blackfriars. Renowned not just for helping establish a new nation, Franklin is also credited with inventing an early form of swimming fin (that looked more like hand paddles than flippers) at just 11 years of age – an early expression of his lifelong love for the aquatic arts.

Monet, Faraday, and Dickens captured the lure of the Thames

In 1773, he described his invention as “two oval pallets, each about ten inches long, and six broad, with a hole for the thumb, in order to retain it fast in the palm of my hand. They much resembled a painter’s pallets. In swimming, I pushed the edges of these forward, and I struck the water with their flat surfaces as I drew them back. I remember I swam faster by means of these pallets, but they fatigued my wrists. I also fitted to the soles of my feet a kind of sandals, but I was not satisfied with them, because I observed that the stroke is partly given by the inside of the feet and the ankles, and not entirely with the soles of the feet.”

In 1807, English Romantic poet George Gordon, better known as Lord Byron, also swam a distance of some three miles from Lambeth to Blackfriars. Three years later, the influential writer would go on to swim across the storied Hellespont, now called the Dardanelles, in Turkey to prove whether the ancient Greek tale of Hero and Leander’s tragic love affair (in which Leander swam the strait nightly to visit his love, Hero, on the other side) could possibly have been true. Byron proved the story might well have been founded in fact.

Celebrated Victorian novelist Charles Dickens also took to the Thames for recreation on occasion and the river featured prominently in many of his serial stories. In fact, in his final finished novel, “Our Mutual Friend,” the River Thames serves as a primary character. Following in his father’s wet footsteps, his son, Charles Dickens Jr, wrote an “unconventional handbook” called “Dickens’s Dictionary of the Thames from its Source to the Nore.” Much like Davies’ more modern take on the subject, Dickens’ book described in detail the villages and peoples who populated the river in his day.

Channel Prep School

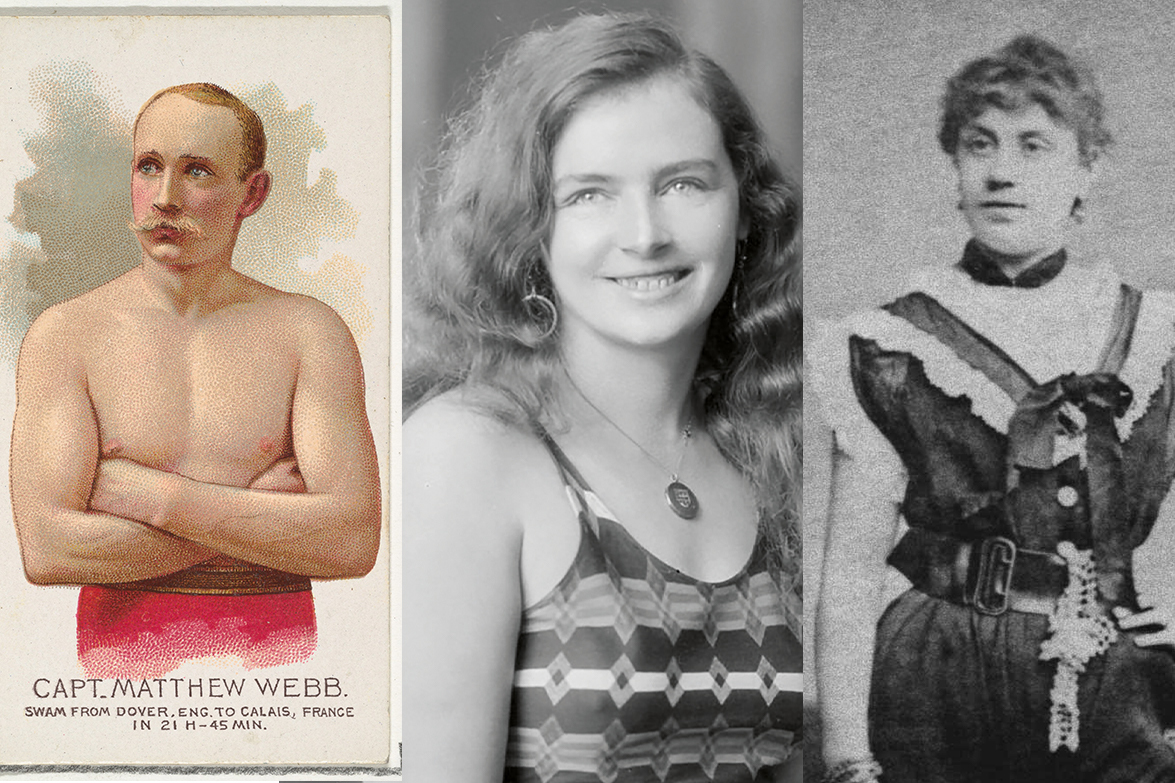

Among the most robust users of the River Thames are the many marathon swimmers who have leveraged its waters as training grounds and self-promotional stages. Captain Matthew Webb used a swim in the Thames to drum up support for his forthcoming attempt at the English Channel. Writing in his 1974 tome, “Wind, Waves, and Sunburn: A Brief History of Marathon Swimming,” Conrad Wennerberg noted that a big swim in the Thames could open the floodgates of sponsorship for Webb’s swim in August 1875.

“Realising that an attempt on the Channel took money – money that he didn’t have – he proceeded on a well-formulated series of actions that were to lead to eventual success. With the acumen that would do justice to our present day public relations men, he announced that he would undertake an 18-mile swim in the Thames River.” The swim launched from Blackwall Pier and finished at Gravesend, and turned out to be a sound investment. “Betting 10 pounds on himself at 10-to-one odds, he entered the water and calmly proceeded by breaststroke down the Thames.” After five hours, he collected his winnings. “Webb’s accomplishment would be considered nothing today,” Wennerberg notes, “but in his time, it was.” A couple months later, he made history in the English Channel.

The following year, London-born Frederick Cavill – who would later emigrate to Australia and propagate a whole family of marvellous swimmers – swam more than 20 miles from London Bridge to Greenhithe, which at the time was believed to be the longest distance ever swum in the Thames. Cavill would make his first attempt to cross the Channel the following month, but “was taken from the water three miles from his destination,” the Australian Dictionary of Biography reports. Nevertheless, the gutsy attempt earned the self-anointed “Professor of Swimming” much fame and adulation, and with that he launched a fantastic and truly global swimming career.

Annette Kellerman – who would go on to become the most famous swimmer of her day – similarly used a Thames river swim to raise her profile and garner support for bigger events to come. In 1904, at the tender age of 17, Kellerman set sail from her native Australia and landed in England, taking centre stage in the biggest market for swimming entertainment. Once there, she completed a 27-kilometre swim down the Thames from Putney Bridge to Blackwall to the delight of thousands who’d flocked to the river’s edge to see the starlet, who would later become a Hollywood box-office power and a staunch advocate of women’s rights. The swim garnered the attention of Lord Northchilffe, a newspaper mogul who owned the Daily Mail and the Daily Mirror. He offered to fund Kellerman’s upcoming English Channel attempt.

Fellow Channel aspirant Mercedes Gleitze launched another extraordinary Thames swim on 18 July 1927. Her effort spanned 120 miles over 12 days and transpired in the midst of her years-long effort to become the first woman to swim the English Channel. Although American swimmers Gertrude Ederle and Amelia Gade Corson beat her to the punch, Gleitze claimed the third spot on the women’s finishing list when, less than two months after her Thames adventure, the legendary London typist became the first British woman to swim the English Channel.

Marathon swimming pioneers Webb, Gleitze and Beckwith

While for some, the goal was to swim the channel, for others, a Thames swim served as a consolation prize. In 1912, plucky, pint-sized Rose Pitonof of Boston, Massachusetts, swam 16 miles down the River Thames from Richmond to the Tower Bridge in London after poor weather prevented her from making an attempt to swim the English Channel earlier that summer. She completed the Thames swim in 4 hours, 32 minutes using a strong breaststroke and got to meet “one of the [unnamed] big leading sportsmen in England,” who gave her “a lovely medal,” she recalled shortly before her death as part of an oral history of laudable Bostonians compiled in 1980.

Born in 1895, the tiny girl from the Dorchester neighbourhood first garnered attention at age 10 when she swam a mile and a half across part of Boston Harbor in just 33 minutes, a startling record in icy water for a child wearing a woollen bathing costume. She’s best remembered today for being the first woman to swim the then-12-mile Boston Light Swim course (which she did at age 15 in 1910), and for an eponymous annual event in New York that recreates her successful 1911 swim from Manhattan to Coney Island.

A Big Swim for Big Names

In the late 19th century, marathon swimming was a glamorous sport. Not because of the layers of grease swimmers would don before wading into cold water, but because the general public – which was largely incapable of swimming – was so enamoured by the abilities of the half-fish people who undertook long-distance swims. One of the most popular of these Victorian-era aquatic entertainers was Agnes Beckwith, the most famous of the Beckwith Frogs, a family of swimming demonstration artists based in London.

In addition to performing in the family shows, Beckwith was also a decorated competitive swimmer. When she was 14, she became the first woman to swim five miles down the Thames from London Bridge to Greenwich. The swim was apparently a means for her father, Professor Frederick Beckwith, to earn back a poor investment in a six-mile swim Webb had undertaken a few weeks earlier.

As Davies reports, Frederick Beckwith, “like most professors of swimming was a lover of spectacle and savvy promoter,” who had helped train Webb for his crossing of the English Channel and subsequently organised a nearly six-mile swim in the Thames for Webb to build on his notoriety. However, Frederick Beckwith lost money on the venture because there just wasn’t enough spectator interest. His staging of [Agnes] Beckwith’s five-mile Thames swim soon thereafter was “both a publicity stunt and a money-making scheme,” Davies writes, that kicked Beckwith’s endurance career into high gear. The following year, she swam 10 miles down the Thames from Battersea Bridge to Greenwich, and in 1878, she completed a 20-mile swim from Westminster to Richmond and back to Mortlake, Davies reports.

Another legendary female swimmer, the “Queen of the English Channel” herself, Alison Streeter, who has crossed the Channel 43 times and completed a triple-crossing, also made waves in the Thames in 1986 when she swam upstream an astonishing 68 kilometres from Gravesend to Richmond in just 16 hours.

In 2006, Lewis Pugh ran and swam the length of the River Thames, as part of a campaign to draw attention to a drought occurring in the UK at the time. Pugh writes in his blog that he expected the swim to take 10 days, but it dragged on for 21 because the water level had been so negatively impacted by the lack of rain. “When I arrived to begin my 350km swim of the River Thames from source to sea, there was no water whatsoever. I had to run 40kms in blistering heat before I found enough to swim in.”

Although many swimmers have used a swim down the Thames to prepare for an attempt to tackle the Channel, it can go both ways. In 2011, comedian David Walliams – who’d raised more than £1 million for Sport Relief when he swam the English Channel in 2006 – swam 140 miles down the Thames, raising an additional £2 million for Sport Relief. Unfortunately, Walliams needed relief of his own after the swim; he contracted giardiasis, a diarrheal disease caused by a waterborne parasite, and slipped a disc, which required spinal surgery in 2013 to correct.

For all these swimmers and the many millions more who will never be singled out or heralded for their achievements, swimming in the Thames is a special experience that Philip Hoare sums up quite neatly in a 2015 Guardian article thusly: “To swim the Thames is to swim between myth and history.”