Overcoming addiction

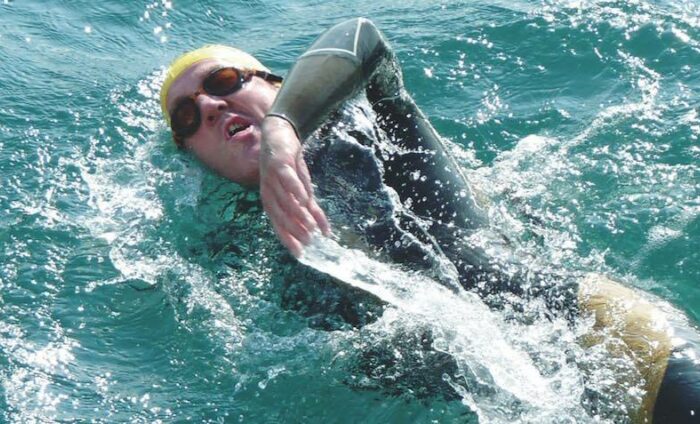

In September 2014 recovering alcoholic Paul Parrish attempted to become the oldest person to complete the Arch to Arc triathlon, running 87 miles from Marble Arch to Dover, swimming the English Channel and cycling 182 miles to the Arc de Triomphe, Paris

“This will never end. It will never end. I have been swimming for 17 hours. I only know this fact afterwards and I actually think I have been swimming for much longer. No one is allowed to tell me anything. My crew are under strict instruction to say nothing about time, place or distance left. It has been dark since 7pm the previous evening. That was the last time I had any visual reference other than my pilot boat, Gallivant, bobbing next to me. I know it must be morning soon and the fact that I can’t see light in the sky is confusing me. All is darkness. All is sea. All is hopeless.

“Stroke, one, two, three, head out, stroke, one, two, three. This same action, this same mantra repeated for many hours. At first it had been comforting. I had felt strong and the adventure had seemed possible – probable, even. But now – many, many hours later – it is over. I have failed. I know from all the things that I have read and from all that I know about my own ability that I should have finished this swim hours ago. I have spent the summer swimming with other Channel swimmers and I know from those that have already been successful where, in the pecking order of swim times, I should be. I should be warm, back on board Galivant and heading to Calais. The fact that I haven’t finished swimming by now means something has gone horribly wrong. Something going horribly wrong on a Channel swim preceded by an 87-mile run will mean a compounded disaster that the human body won’t have the resource to deal with. The blood supply transferring oxygen around the body needs organs that are well fed to keep pumping life around me. But every store of energy in my body must be used up now. There can’t possibly be any more left. Any chance of success has gone.”

When people ask me how I managed to swim for the 17 and a half hours that I spent in the English Channel that September night in 2014, I answer by saying: “I could keep going because I am an alcoholic”. It’s the answer that I think is the most honest. It is not the answer people want and it frustrates swimmers who want tips on nutrition and training plans.

Extensive and expert advice on those topics is available on the internet, but very few places help with the mental discipline and psychological steps needed to prepare for a big swim. For 20 years I drank alcoholically and lived in a place of darkness. In the 17 subsequent years that I have spent in recovery, I have come to apply the simple steps that have motivated me to stay sober each day to endurance swimming.

Simple steps can get us to our goals, be they swim goals or a life free from addiction. It is these steps that I want to share now. They are not difficult and they are simple concepts, not just for sports training, but for life itself. After all, is life not the greatest endurance event that we undertake?

We start out on a big swim feeling positive and full of expectation. Then reality bites and we have to maintain our forward progress through all the challenges that are thrown at us. Sometimes we wish the pain would just stop and sometimes we are in awe at the wonder of it all. And at some point it will end and I hope that we look back on our lives in the same way that we look back on a tough swim: “That was one hard event, but god, was it worth it!”

So let’s take a closer look at the steps we can use to succeed when it may feel easier to give up.

Paul aboard Gallivant

Enhance your life

This is a simple way to get started. As you read this magazine I hope that you are entertaining ideas of challenges that you would like to attempt. Are there iconic swims that you dream of doing? Do you fantasise about those big swims but tell yourself you couldn’t possibly attempt them? Well, here’s lesson one: it’s time to get real. You have just as much right to do these things as anyone else. Having a burning goal or ambition is crucial to extending yourself. If you are swimming for fitness with no specific aim in mind then this article may not be for you. But if you have an ambition that seems too far out of your reach, then read on.

I have been in a position of unlucky privilege. As an active alcoholic everything apart from alcohol consumption was an untouchable dream. My every waking thought was a fantasy about what I wished I could achieve if I didn’t drink. Like anyone recovering from a serious illness, I have come to value life’s possibilities. In recovery I worked at a cancer hospice where I saw people receive a diagnosis. Just like that, their life was altered. Often those close to death would express regret for things that they wished that they had done. It has made me acutely aware that we have just one life. Life is an adventure and, as far as we know, this life is the only one we have so go and attempt that challenge that you currently feel unworthy of. Make your dream a reality. Don’t end up regretting swims that you wished you’d done.

One day at a time, one hour at a time, one minute at a time (part 1)

So you have picked an event that now makes you feel nervous about the scope of the challenge. Maybe it requires a huge leap from the distances that you are currently swimming, or is a move from the safety of your local pool to the

vastness of the sea. How do you get to where you want to be?

This is one of the most common reasons why people don’t attempt their dreams. We look to the far horizon, when we should be looking much closer to home. If you had told me 17 years ago that to live a constructive life I could never take a drink again, I would have run to the nearest pub and never come out again. Instead, I was told that for just one day I didn’t need to take a drink. My confused brain could just about handle that concept. Once I had done that day, I would wake up again and say to myself, “Just today, not any other day, just this day, I will not take a drink.” I have done this for the past 5,965 days. When I do look beyond the day I can see how my horizons have broadened and brightened. So with your event think on a day to day basis. What training do you need to do today? Keep it all in the day and don’t worry about anything else. Each little day will build the foundations of a dazzling horizon.

Say you have never swum more than a mile and your dream is a 21-mile swim. Don’t assume that 21 miles is impossible so why even bother? Instead ask yourself if a mile and a half is possible. Of course it is. If you can swim a mile and a half, what then about swimming two miles? And so on, until 21 miles no longer appears impossible and instead becomes achievable (the same applies to time in the water, or increasing speed). I know that this seems so simple that it doesn’t need to be said, but I am amazed that this basic formula to endurance success isn’t applied more often. I learnt it from a member of the GB women’s rowing team who applied knocking off a 1/100th of a second once a week to her training to win a medal. So simple and effective.

Paul on his way to France

The fear

So you have picked that “you only live once” event and are training hard, adding increments of distance, cold or speed to take you to your end goal. The event gets closer and the week before the event you feel terrified. There will be times when you wake up at night and lie there, pulse racing, brain whirring, wondering what on earth you have done. I could say relax, but you won’t. Instead, embrace that feeling of terror. The more frightened you are the more satisfied you will feel when you have completed the challenge. You have to trust this. Not everyone does and, as event organisers will tell you, a good 15% of paid up competitors will just not turn up on the day. Sure, some no-shows will be because of injury or lack of training (which is probably a subconscious reaction to fear), but many absences will be a result of some form of anxiety.

There is no easy way around this. You have to accept that fear is natural and uncomfortable, but it should not stop you. It serves a purpose to protect you, but the brain cannot always differentiate between real and perceived danger. As I stood at the jumping-off point 17 years ago I was terrified. I could never imagine a life without alcohol. It was what bound me to this world; it was what defined me. Yet neither could I imagine a life with alcohol because I knew I was headed towards increasing insanity and ultimately a premature and miserable death. So I jumped towards life without booze and expected that fear would smash me in the face. But fear is a chimera and the punch never came. Instead a strange beauty and acceptance made it possible for me to move forward. If you confront your fear and move towards it, you will find it is not the snarling beast you imagine.

Think about your big swim in another way. The event is on a Sunday, for instance, and you know that you will move through Sunday as a living, breathing entity, come what may. And after Sunday you will still exist and you will wake up on Monday as normal (bear with me on this, reader). You can choose to move through that day any way you wish. You may choose to not swim, sit on the sofa and eat pies, watching re-runs of Downton Abbey. But you may choose to challenge yourself. You choose, but how you feel on Monday morning will be very different depending on your choice. In scenario one, after a weekend on the sofa you will feel disappointed that you didn’t attempt the event and that disappointment and shame will stay with you for a while. In scenario two you will wake up on Monday tired but jubilant with great memories that will be replayed for years to come. It is your choice. Any time that I have been tempted to drink, I have applied that same principle. I can choose to do one thing or the other at the weekend but how I would feel on that Monday morning would be radically different.

Paul enters the water at the start of his Channel swim

One day at a time, one hour at a time, one minute at a time (part 2)

You are finally off on the challenge. You have faced up to your fear, confronted your self-doubt and you have put in the hard training in the weeks and months leading up to this day. Getting into the water was terrifying, but a strange thing has happened: you are now underway and the fear has dissipated. Fear has been replaced by determination and you are beginning to make progress with your challenge.

My experience is that the first part of any big event is rather joyful. You have put in the training and so you are feeling really good. Your body should now be in good physical condition and will respond well to the initial pressures you are about to put it through. But a big challenge is a big challenge for a reason – it will begin to test you. Gradually, the swim will begin to bite. It will start with a discomfort, maybe real or imagined. Then there will be those tell-tale signs of tiredness: irritation with yourself, irritation with your crew, a sense that progress is slowing. Doubts will begin to rear up in your mind. Small things will become big things and the brain will do its utmost to tell you that you should call off your attempt.

I love my brain a lot, but it can at times be responsible for some huge acts of sabotage. Remember, it’s just doing its duty and telling you that you are becoming depleted of crucial energy stores. When humans were hunter-gatherers it could take nine hours running an animal to exhaustion in order to kill it – our brains are hardwired to conserve energy and keep ourselves alive during lean times. The best way to do that was to stop moving and save calories. That ancient brain is still as active as ever and is forever telling us to stop and sit back as soon as it thinks the body is in danger of depleting itself. That is the main reason why most forms of exercise seem like a bad idea when we are sitting in our warm, comfortable homes. No matter how experienced we are and how much we understand the benefits of exercising, packing our swimming costume and towel and walking to the pool seems like a bad idea thanks to our risk averse, comfort-loving ancient brain.

Sometimes the ancient brain is in danger of winning and these discomforts become too big for you. It’s at these times that you have to fall back on the most important thing that any addict knows: this feeling will pass. The key part of staying clean as an addict is

understanding that life is always going to throw problems at us. These problems will build in our heads, if we let them, and give us feelings that can cause us to react in the most damaging of ways. Long ago I learnt that these horrible feelings were as insubstantial as bubbles and that if I didn’t react to them they would magically disappear and I would stay safe… until the next situation came along to test me.

So, like a recovering addict, just keep swimming and the discomfort will soon pass. Sure, there will be other irritations, but that fatigue, hunger, anger or hurt that could have made you give up on your once in a lifetime event will have passed. (Having said that, make sure that your crew are vigilant and talking to you. If you push too hard, you could genuinely be putting yourself in danger and you will be exhibiting warning signs that your crew need to interpret. Chances are that if you have pushed that hard you will be in a state of hypoxic bliss and will long since have stopped feeling irritated.)

When the event begins to bite, remember all that you taught yourself in training. If you can swim one mile, you can swim another half a mile. If you can swim half a mile, you can swim another quarter. Don’t think about the entirety of the event; break it up into segments that are mentally manageable. Over the distance of 21 miles a single mile strikes me as something that is mentally acceptable. Apply similar ratios to your event. The end can be too much to contemplate, so you must try and live in the moment. If you keep plodding on, you will get there.

Progress not perfection

You are now well into the event and not only is it tough but you can feel your form beginning to disappear. That beautiful stroke that you have spent hours perfecting in the pool has been reduced to thrashing in the water. Not only are you hurting but you can recognise how fatigue is making you even more inefficient. This is another of those danger times when your brain will tell you that your swimming is not good enough to get you there.

Ignore this. It’s just another example of the brain sabotaging you. In recovery I have done so many things that are wrong and do not fit with the lifestyle I have adopted. I am human and, as such, am irrevocably flawed. I am not perfect, but I want to be. Again, it can be easy to self-sabotage and ask myself what is the point of all this striving because I will never be any good. I know it’s nonsense thinking, but even while recognising it for its destructive nature it is incredibly powerful and can undermine all the hard work I have put into staying sober. The brain may tell me that a drink can solve the problem and I don’t need to worry any more. This is why addicts have a lovely mantra: “progress not perfection”. When in the throes of a tough swim repeat it and repeat it. Forget how you look, how you feel, just keep moving forward. Endurance events are never pretty. Their nature means that the longer they are, the more the chances of things going wrong. Accept that this will happen and keep going forward and fight dirty. At some point you may have to sacrifice technique for expediency to get the job done.

The end

I can’t tell you how your event will end, but if you can keep some of those tips in your head, it will end well. I can’t say you will complete it, but just by attempting your challenge you will enhance your life. So on finishing I ask you to consider my experience of attempting my impossible dream:

Paul touches land in France

“All is lost. I am done. I am distraught. The left side of my body is in agony and I am swimming with only one side in working order. I will never finish now. I know one thing, though; one crucial, lifesaving piece of information. This will pass. At some point my ordeal will end and I have chosen not to end it myself. I have accepted failure but not defeat. I have made a decision that I will wait for my crew and Mike Oram, the pilot, to end the swim. I will not give up until they tell me to do so. I can keep going another minute, another hour, even if it is futile.

“In the depths of resigned despair things begin to happen quickly. I am aware that Dan, my designated support swimmer, has jumped in. To my addled, depressed brain, that can only mean one miserable thing: he wants me to push hard so that we can beat another tide, otherwise it’s another six hours in here. I am close to despair. I can’t do this anymore and I can’t speed up. I hurt and I ache and salt water has taken over my body. Not another tide, please god, no.

“Then Gallivant is gone. It is not on my left hand side where it has bobbed for 17 hours. As I realise that I am alone the miracle happens. The most remarkable thing that has ever happened to me. My right hand touches sand. Then my left. I stop swimming wondering what I have hit in the pitch black. I put my feet down. There is sand beneath my feet. The sand of France. I carry on swimming, but now my strokes are uneven because I am sobbing. Sobbing with relief, sobbing with joy, sobbing with jubilation. I have swum the English Channel. And contained in that simple sentence are the images of a lifetime. The images of 5.24am on 12 September 2014. I replay those moments every single day of my life. Nothing can take them away from me. Writing this final paragraph my eyes become tearful as I remember those moments. I hope that for those of you who are reading this with a goal in mind or a goal already embarked upon, that you have a moment like my 5.24 am. Go well.”