Save our pools

Rowan Clarke investigates why it’s more important than ever to fight for your local swimming pool

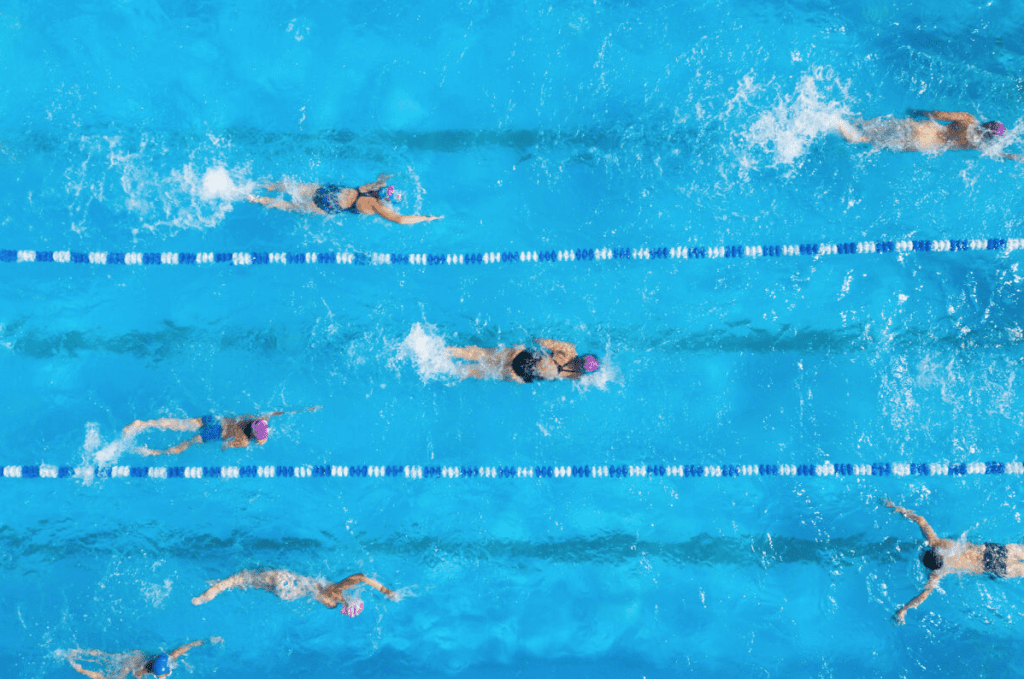

Once the outdoor swimming bug has bitten, it’s hard to imagine ever doing lengths in a chlorinated tank again. No matter how much you prefer swimming outdoors though, it’s harder to overlook how crucial swimming pools are to public health, wellbeing and safety, to communities and to the future of swimming – indoors and out.

You might also like:

Over the past 18 months, the UK’s swimming pools have faced a crisis. Rising energy costs, shortages in staff and facilities and inadequate investment have led to a lack of swimming opportunities for us and many permanent pool closures. It sometimes feels like our local pools are crumbling into extinction. But all is not lost. As Swim England publishes its Value of Swimming report, smart new pools like Brighton’s Sea Lanes are opening and community groups are finding innovative ways raise funds. There’s also an increasing recognition of how valuable swimming is to everyone on all levels. So how do we save our pools?

From cradle to grave

We’re preaching to the choir here, but swimming really is uniquely brilliant for our health. As outdoor swimmers, we know that a big element of the physical, mental and wellbeing benefits we enjoy come from simply being in water. The weightlessness, the freedom of movement, the cardio and muscular workout, the sensation of water on our skin.

Being in water also levels out our differences as individuals and communities. From learn-to-swim classes and hydrotherapy for people with disabilities to masters swimming, lifesaving clubs and aquafit, the ways in which we can enjoy the water are varied and all-encompassing. And it’s joyful, healthy, fun, bonding, bringing untold benefits for our mental health and sense of wellbeing.

“It is no exaggeration that learning how to swim, and having the water safety knowledge to be safe in, on and around the water, is a life-saving skill,” writes Jane M Nickerson, CEO of Swim England, in the new Value of Swimming report. “The magic of swimming and where it is unique is that there is some form of aquatic activity to support people at every stage of the life cycle, from parent and baby sessions through to dementia friendly sessions and everything in between.”

The new report goes so far as to put a monetary value on swimming. In 2022, it generated more than £2.4 billion of social value through improved physical and mental health, increased life satisfaction and individual, social and community development.

Learning to swim

Yet, a staggering 14.2 million adults in the UK can’t swim the length of a 25-metre swimming pool. And it’s only going to get worse: All Parliamentary Group for Swimming predicts that by 2025/26, 57% of children leaving primary school will be unable to swim this distance.

The problem is that 72% of school swimming lessons take place in public pools – the very pools that are most under threat of closure. In fact, Swim England predicts that by 2030, almost three-quarters of local authorities could have a shortage of swimming pools. But it’s not just swimming lessons in public pools that are struggling.

Private swim schools don’t just play a critical role in teaching people to swim, they also fill in the gaps that the national swimming pathways don’t cover such as adult learn-to-swim classes, open water, triathlon and baby swim schools.

“Pools have been particularly difficult for us since the pandemic – many didn’t reopen and a lot have since closed or put their prices up massively because of the energy crisis,” says Hannah Smith, Director of Aquatics, Pools and Facilities and Training at Water Babies. “We’ve had some franchisees lose 50% of their business overnight because they’ve lost a pool. We rely on third party water space – it’s outside our control, so it’s really difficult for us to come back from that.”

Clubs and competitions

From recreational swimmers to elite athletes, county to Olympic level, swim clubs, para swimming, diving, water polo and artistic swimming are also competing for diminishing pool space. As are open water swimming groups, triathlon clubs and a whole raft of other water sports – from novice kayakers and scuba divers to triathletes and underwater rugby teams.

“The confidence boost that a child gets from completing their first ever triathlon is beyond belief and for many of those children, it was the start of a life of regular exercise and vastly improved self-esteem,” says Ruth Pitchers who ran a triathlon club for children aged 8 upwards – until her local pool was decommissioned.

“It was an ideal venue for swimming progression as well as many swimming related activities such as octopus, canoe polo, diving, lifeguard and teacher-training as well as triathlon,” she says. “Swimming and related activities are therapeutic for every participant at every level and our club changed the lives of many – continued athletes who I still bump into today. Just this summer some ex-pupils entered the Bristol triathlon, Dart 10k, and various sea swims and have become teachers and coaches themselves.”

Lifeline for communities

The Value of Swimming report identifies the role that swimming clubs like Ruth’s bring to a community. It says: ‘They support community identity and development, fostering local civic pride, offering opportunities that help tackle social isolation and loneliness as well as improving physical and mental health.’

The value of beloved swimming pools to communities is clear every time a pool’s threatened with closure. Powerful campaigns such as Bucksburn Swimming Pool’s in Aberdeen may just save them, while community trusts have shown that they can successfully operate pools.

“I think our long history and year-round offer in a beautiful outdoor setting on the edge of Bushy Park, combined with our friendly, responsive team are important factors in developing the special sense of community at Hampton Pool,” says Jane Savidge, Chair of the Hampton Pool Trust. “Hampton Pool is run by a charity – we’re not a local authority pool and we have little by way of public subsidy. Despite this, we’re an embedded part of local authority swimming provision, which means that when we’ve struggled due to the energy price increases and cost of living crisis, Hampton Pool Trust and the pool team have had to be imaginative in finding new and varied sources of funding.”

This model of pools being run by the community for the community has lots of benefits, although more lidos like Hampton Pool need to become embedded in local authority provision. And yet, despite the effort of community groups, many pools are still being shut down.

“Covid felt like an opportunity for the council to close the pool and sadly, they never re-opened it despite numerous campaigns. In my opinion, the benefits to so many far outweigh the cost of providing a facility with tax payers’ money,” says Ruth, who campaigned to save her local pool. “Outsourcing the management of a community facility to a profit-orientated organisation seems to be the wrong approach. Compare this to a community-run pool like Portishead Open Air Pool where the number of swims per year rose significantly when the community took over.”

Time for serious investment

So, if there’s so much value in swimming and so much impetus from communities to keep our swimming pools open, why does it feel like they’re disappearing at an alarming rate?

Since 2010, more than a thousand publicly accessible pools, including around 450 local authority owned pools, have been closed, mainly because of how much they cost to run.

Aging pool stock is a huge problem here. With poor energy efficiency, old pools can be unreliable, environmentally unsustainable and costly – especially as energy costs have tripled in the last year.

“Around 40% of our pool are over 40 years old, which means that they need investment. There is technology available that can enable us to upgrade our facilities in order to help a pool run more efficiently,” says Swim England’s Head of Facilities, Richard Lamburn. “These facilities should have been upgraded before now to ensure financial and environmental sustainability. However unfortunately there hasn’t been the investment, and that’s probably the biggest difficulty that we have.”

This has a huge knock-on effect for operators like Charitable Social Enterprise GLL that runs pools and open water venues across the UK under the name Better.

“Facilities owned by local authorities are steadily declining; this has been this case for the past decade,” says Andrew Clark, Head of Sports and Aquatics at GLL. “Swimming provision is not a statutory service that local authorities have to provide. Therefore, if they can’t afford to provide it, they won’t. Without publicly accessible and affordable swimming pools there is no school swimming, there are no affordable learn to swim programmes; there’s a whole community that exists and evolve around a local swimming pool.”

A new vision

What if we change how we see swimming pools? At the moment, they’re leisure facilities – not as important as health and social care facilities. But, if swimming is so good for our health and wellbeing, surely pools ought to be an integral part of health and social care infrastructure?

In its report, Swim England explains how that would work. Using community groups Mental Health Swims and Open Minds Active as case studies, it demonstrates how successfully swimming can be prescribed for mental health, physical health and social issues such as isolation and lack of confidence and argues for better integration between health, leisure and local authority partners.

Geographically location is also significant here. Beautiful, historic lidos in wealthy towns are one thing, but subsidised inner-city public pools have the potential to bridge racial, social and financial inequalities. It’s particularly shocking that since 2010, areas of greatest social deprivation have lost three times as many publicly accessible pools compared with the wealthiest areas.

“In new design, we try to ensure that facilities are located within those communities that should be benefiting, but also that the design enables access,” says Richard Lamburn. “A prime example is the Sandwell Aquatic Centre that you saw host the Commonwealth Games. What you didn’t see, was that there’s a studio pool that’s completely shut off from any view for user groups who need that privacy.”

Hope for the future

It’s clear that swimming and waterbased based activities have immeasurable benefits for our physical and mental health, social wellbeing, quality of life and communities and safety. Individuals, communities and organisations have the impetus and drive to bring us those benefits.

So, all we need are great places to swim. But how do we get there?

Investment in swimming pools and leisure centres is key: The government has awarded a £60 million one-off support fund in England, there’s a National Lottery Heritage Funding award for Future Lidos, but it’s still not enough.

Plus, it’s about more than money for bricks and mortar. By reimagining the purpose of our leisure facilities and sharing a vision for integrating leisure, health and wellbeing across all levels of government, there’s the potential to elevate the case for better pools.

Reports like Swim England’s Value in Swimming, initiatives like their Water Wellbeing Programme, organisations like Mental Health Swims, Open Minds Active, Water Babies and Everyone Active give us so much information, statistics and examples of why swimming is so uniquely brilliant for everyone. And that’s a great position from which to make the case for greener pools, cleaner outdoor blue spaces and better social prescribing.

From where we’re sitting, we can help too. Supporting your local pool, writing to your MP, volunteering to help at your children’s swimming club or with school swimming – any way in which you can get involved. We all started swimming in pools and so it’s time to show our appreciation.

Support Swim England by signing up as a Supporter, Campaigner or Champion and you can help fight for our pools and sports and for better access to cleaner water to swim in.