Tarn Baggers

In the 1950s, Colin Dodgson and Timothy Tyson swam in every tarn in the Lake District. Richard Nelsson recounts the feats of two naked adventurers

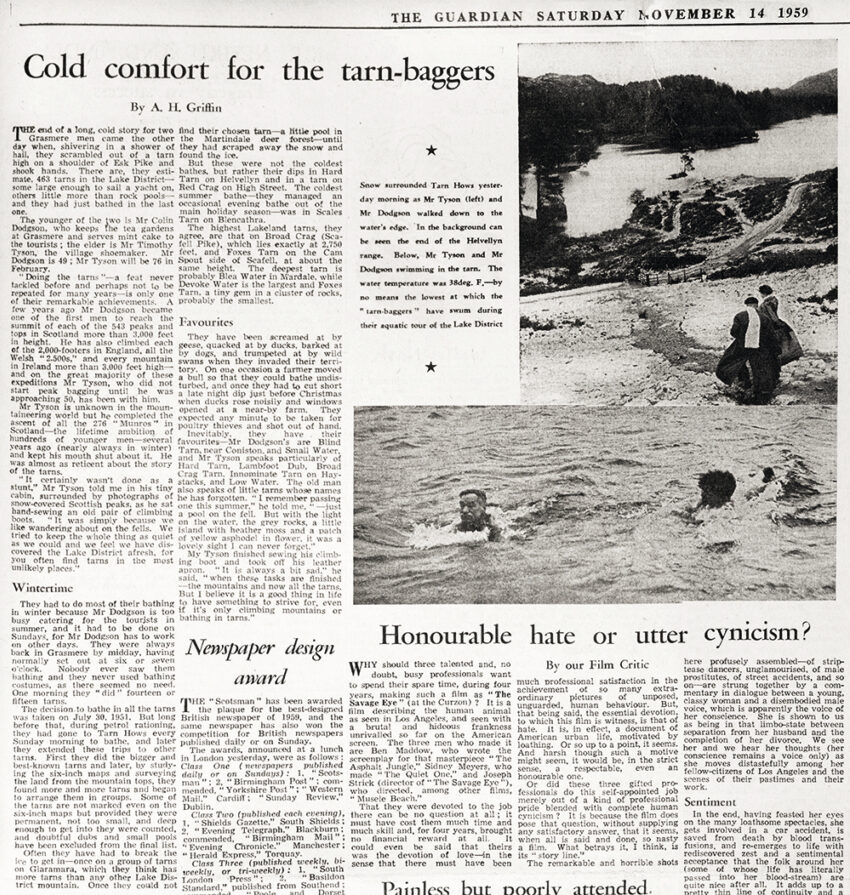

On a bleak October day in 1959, two swimmers shivering in a biting shower of hail scrambled out of a high mountain tarn and shook hands: they had just completed one of the most remarkable outdoor swimming feats of recent times.

Over an eight-year period, Colin Dodgson, 49, and Timothy Tyson, 75, had succeeded in bathing in every tarn – 463 by their reckoning – scattered across the English Lakeland fells. Everything from the largest sheets of water to reed-choked ponds had been visited, often in the winter months and at times requiring them to dig through deep snow or break the ice to reach the water. All swims were done stark naked.

The sport of tarn bagging had been born. That is, visiting, and ideally swimming in, every one of the hundreds of mountain lakes to be found in the Lake District National Park.

No doubt if the challenge was being done for the first time today, each swim would be photographed and Instagrammed before even getting changed. Back in the 1950s, apart from a couple of newspaper reports and local television appearances – one reportedly with a young Michael Parkinson – little has been written about these outdoor swimming pioneers.

Colin Dodgson and Timothy Tyson – a shopkeeper and a cobbler from the Lakeland village of Grasmere

Outdoor swimming pioneers

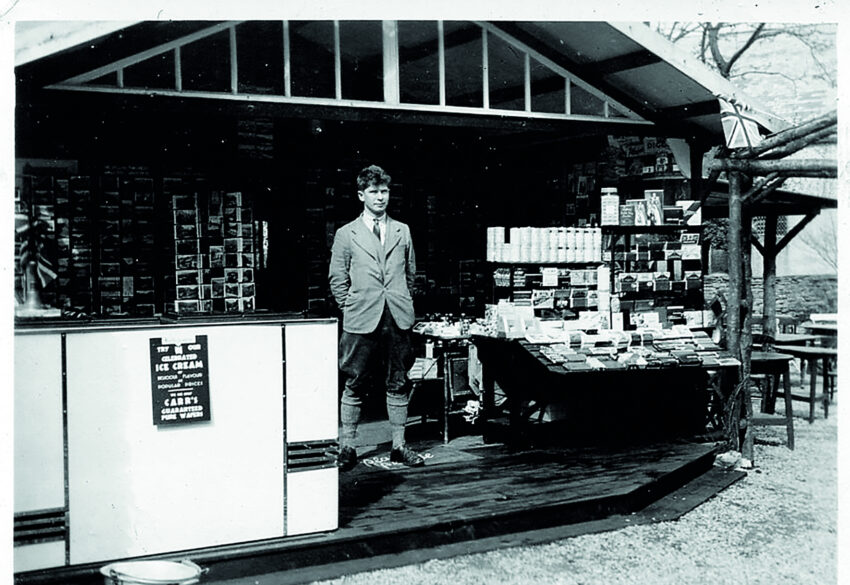

Colin Dodgson and Timothy Tyson both lived and worked in the Lakeland village of Grasmere. Colin, a stocky man with a thick mop of tousled hair, ran a couple of shops and the local Tea Garden – a riverside cafe serving tourists and walkers. Tim, a short, bespectacled grandfather, was the village cobbler.

The idea behind ‘collecting the tarns,’ came after many years of serious ‘peak-bagging’. By 1951, Colin, a man of incredible stamina, had climbed all the Scottish Munros – mountains over 3000 feet – as well as all the major tops in England and Wales. Tim, who joined him on many of these adventures, was equally remarkable. Surviving two years in the first world war trenches and ‘going over the top’ three times, he only began doing the Munros at the sprightly age of 50.

A new challenge

After spending every bit of spare time motoring across the country in an old car, laden with primus stoves and ice axes, Colin in particular was looking for a more manageable challenge. As his granddaughter Rebecca Dodgson put it, “he needed a new purpose for hikes and seeking out tarns seemed as good a one as any.”

Swimming in the open air wasn’t a totally new venture for the pair. During petrol rationing (pre-1950) they often rode by tandem on a Sunday morning to nearby Tarn Hows for a dip. But on 30 July 1951, a firm decision was made with Colin recording in his diary, “Fine swim in Bowscale Tarn. Weather fine & warm. It was here we definitely [decided] to bathe in all the Lakeland Tarns.”

To begin with they picked off the bigger and well-known tarns. More obscure ones were spotted from mountain tops, while they would pore over Ordnance Survey maps looking for specks of tell-tale blue. Walks would then be carefully planned to take in as many bathes as possible – once as many as 14 in a single day.

Jill Dodgson, Colin’s daughter, recalls all were meticulously recorded, including measurements and grid references. While there is some debate as to what exactly constitutes a tarn, the pair’s definition was simply a patch of water in which you could submerge yourself and then swim – even if only a stroke or two.

Love for the outdoors

However, this urge to ‘bag’ the tarns sprang from much more than just list ticking. Both men loved the outdoors and sought out mountains and corners of the hills for their beauty and remoteness, as Tim told the writer Harry Griffin in 1959:

“It certainly wasn’t done as a stunt, but simply because of our great love for wandering about on the fells. We feel that in our search for tarns we have discovered the Lake District afresh for you often find them in the most unlikely places.”

Nearly all were visited early on Sunday mornings. They’d be away by 6am, pick off a few and be back in Grasmere around midday. A few swims were done on spring evenings and with the re-introduction of petrol rationing following the 1956 Suez crisis, the old tandem was wheeled out once again.

Swimming in the nude

Perhaps surprisingly, family members remember Colin as a terrible swimmer. His dips were often just a few strokes, a wild thrash about with a lot of shouting. That said, he must have enjoyed it as he made sure there was a natural bathing pool next to the elegant bungalow he built on the fell-side above Grasmere. Here he would bathe every Christmas day.

As for the swimming in the nude, Rebecca recalls that this came about because “the first time they decided to swim in a tarn it was just a spontaneous spur-of-the-moment thing and they wouldn’t have had any bathing gear with them. And it then became a point of honour that they had to do all their swims nude.”

This could lead to complications. A few swims were in view of houses, thus requiring secretive night-time dips, while others were on private land and so they ran the risk of being taken for poultry thieves and shot.

They often got dirty scrambling around and had to bathe again, while the diaries record that all too familiar painful process of getting dressed out in the open in wet weather. Hence a drastic measure recorded in September 1951: “Weather very wet. From tarn ran without clothes for half mile to shelter in quarry buildings to get dry.”

Colin Dodgson ran the local Tea Garden

The eyes of the mountain

Tim’s favourite was Hard Tarn near Helvellyn, an elusive pool scooped out of a rock ledge, forming what is best described as a natural infinity pool. Colin found this the coldest swim, although Scales Tarn on Blencathra “nearly took our breath away…but we never caught a cold through bathing.”

In 1960, landscape artist William Heaton Cooper’s authoritative book, The Tarns of the Lakeland, was published. Comprising of 87 drawings and paintings of tarns, “the eyes of the mountain” as he described them, it also included informative commentary.

The painter had his studio in Grasmere so it seemed inevitable he would have compared notes with Colin and Tim. Joy Magenis, Tim’s niece, who grew up in a house next door to her uncle, thinks all three discussed the tarns in the cobbler’s shop. Colin’s son is sure Heaton Cooper gleaned as much information as possible from them, while his research provided a couple of ideas for them, such as an unnamed patch of water on Naddle Fell.

Follow in their footsteps

For budding tarn baggers, Heaton Cooper’s book is the natural place to seek inspiration. Then of course there are all the favourite Lakeland spots suggested in popular outdoor swimming guides.

But to really start following in the pair’s footsteps it’s worth turning to John and Anne Nuttall’s two-volume The Tarns of Lakeland (1995). Here they describe over 80 walks, ingenious circuits linking scores of both the familiar and more remote tarns, many away from the well-trodden paths. The feat doesn’t appear to have been repeated so there’s a challenge waiting for enterprising fell-walker/swimmers.

The Guardian reported their feat in 1959

Something to strive for

And so back to Sunday 25 October 1959 and the final swim, high on the shoulder of Esk Pike, when Colin recorded in his diary:

“Car to Cockley Beck. Bathed in 3 small tarns on way up and 3 pools … Weather very cold & showery with very strong winds on exposed ground. This walk (& bathe) concludes a delightful 8 year pastime i.e. bathing in all the tarns in Lakeland. We have to date bathed in 463 tarns & 144 small pools. We know of no others but there are doubtless more still to be found in odd corners.”

In fact the pair later revised their list, eventually plunging into 534 tarns and 195 ‘pools’. Colin found other walking quests and in 1985 became the first person to climb every hill above 2,000ft in Great Britain. Tim continued to enjoy long walks as well as tending his large kitchen garden. Dubbed a philosopher by Harry Griffin, his final summing up of the tarn bagging quest was:

‘I think it’s a good thing in life to have something to strive for, even if it’s only climbing mountains and bathing in tarns’.

Tim died in 1967, Colin in 1991.

Thanks to Jill Dodgson, Rebecca Dodgson and Joy Magenis for all their help.

Further reading

The Tarns of Lakeland by W Heaton Cooper, 1960.

The Tarns of Lakeland John and Anne Nuttall, Cicerone, 1995