Three Gifts: a contract between two sea swimmers

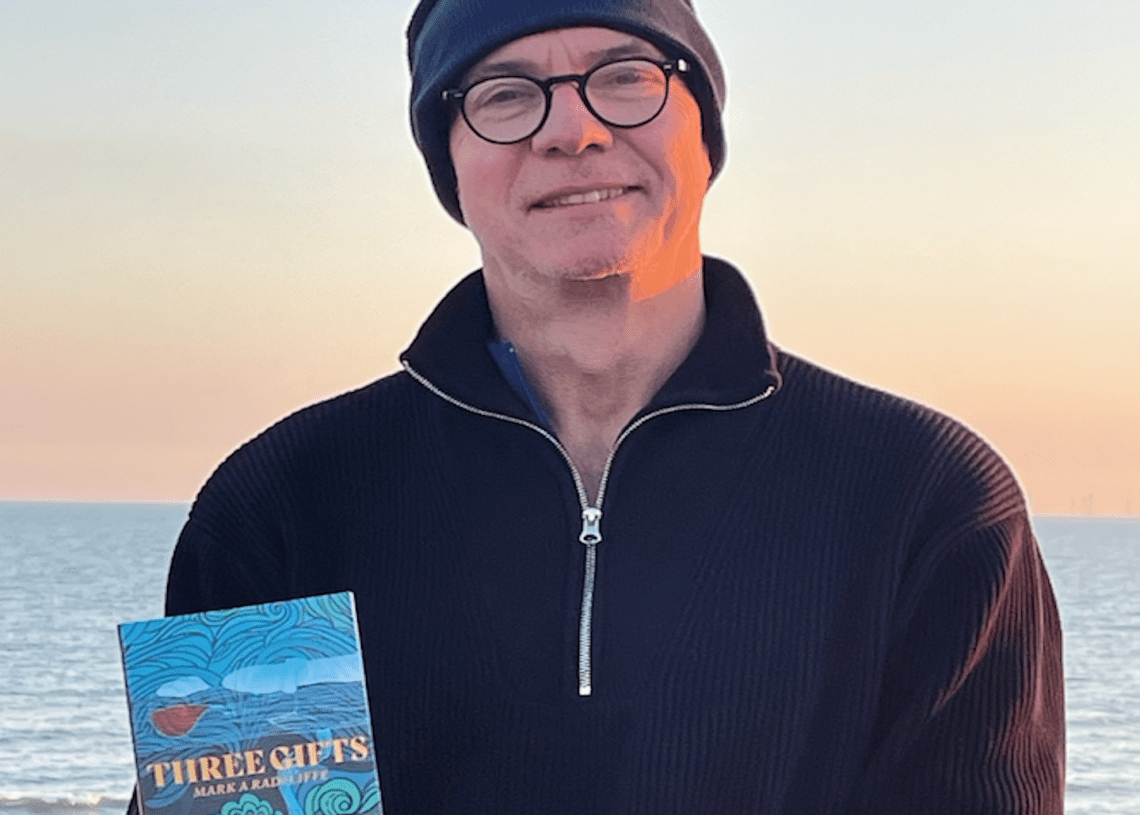

Mark A. Radcliffe’s new book Three Gifts tells the story of an unusual contract between two sea swimmers, and explores one man’s attempt to life a good life, and what it means to love.

If you could have the life of a loved one by trading in years of your own life, how many years would you give? How many lives would you save? Would you know when to stop?

Francis Broad has done just that and has negotiated the day of his death. Now he must come to terms with the decisions he has made.

Mark A. Radcliffe’s new book Three Gifts explores one man’s attempt to live a good life, his sense of responsibility, gratitude and what it means to love.

We spoke to Mark about how his passion for sea swimming informed the tone of his third novel, and what open water swimming brings to his writing and his life.

Mark is based in Brighton and is Programme Leader for Creative Writing at West Dean College.

Mark, tell us about your book. What is it about?

Three Gifts tells the story of Francis Broad. Only child to a single parent living in a council estate in a seaside town in Kent and developing a growing fascination with the sea. When his mother is diagnosed with cancer, the 12-year-old Francis is offered an exchange by a sea swimmer – swap 20 years from his life expectancy to cure his mum. At the time he lives in poverty and watches his grandfather descending into dementia and incontinence. Being old doesn’t look very attractive, and what sort of person would not make sacrifices for their mother?

However, as he grows up he finds out the world needs more from him than just this one exchange, and it can be hard to know what to give away and what to cling on to.

I think it is about gratitude, responsibility and what love looks like. Or it may be about swimming, magic and the residue of poverty.

What inspired the story?

At the beginning I was interested in writing about growing up poor and what that does to people. I found I was interested in parts that might not be considered common.

For one thing, I was interested in gratitude. Simply being grateful for food or the absence of worry or comfort or whatever and how that stays in the skin for a long, long time. And I was interested in responsibility. I think often when men write about responsibility it is treated as a burden to be escaped from or simply tolerated. John Updike’s Rabbit novels being an example, and dare I say Bruce Springsteen being another: ‘Got a wife and kids in Baltimore Jack, I went out for a ride and I never went back’ – (Hungry Heart anyone?). I was curious about the privilege of responsibility.

I have been sea swimming for a long time and I think, at least for me, the sea shows me how I am feeling. If I am preoccupied or irritable or sad or happy, that becomes clearer as I swim.

The second part was a bit more personal. I used to be a nurse, I did some work in a hospice and met a man who talked about how much pain he was in and wondered when he should stop the life extending but pain inducing treatment he was having. He also talked about how grateful he was that his wife, who had died five years earlier, did not feel pain. He said he had prayed that if there was pain to be felt, let it be given to him. And there he was remaining in pain. I imagined he felt that that was what loving her, still, looked like. I thought he was a noble man. And I found myself writing a sort of bargaining story.

What do you hope readers will come away with?

That is hard. It is, I believe, a funny book. It may sound a bit dark but if you write about dark stuff without being funny I think you run the risk of assaulting people with a great big lump of bleak and nobody needs that. So, I hope (and am told) readers come away having laughed in the company of people they like or find interesting or resonate in some way.

And I hope they are moved, stories are about connection, that seems to me to be a thing of the heart so I hope they are moved.

Do story ideas come to you while you’re swimming?

No, I wish they did. They do sometimes afterwards. I have been sea swimming for a long time and I think (and this comes up in the book) for me, the sea shows me how I am feeling. If I am preoccupied or irritable or sad or happy, that becomes clearer as I swim. So I don’t think swimming enables creative thinking, at least for me. Rather it reveals something about where I am at and what I am feeling.

While I would like to say that I clear my mind and something transcendental and profound happens when I swim, I actually tend toward quite a busy mind. If it’s winter I’m trying to judge how cold I am so I don’t over do it. If it’s summer (and bear in mind I live in Brighton), I’m trying not to bump into swimmers, paddle boarders, jet skis or jelly fish. If I’m not thinking about that, I’m trying to work out why my breathing is still rubbish, why my hips aren’t helping and what is wrong with my catch.

Tell us about your own relationship with the sea. How did you get into open water swimming, and what does it bring to your life?

The book is dedicated to a close friend who died of cancer. The conversations we had in the last months of his life around what constituted a life well lived leaked into the book quite a lot.

Many years ago we were working together, teaching nurses and we decided that a way of dealing with stress might be to get in the sea. We bought wet suits and bobbed around for a while, which suited him. He was a big, quite still man who loved boats (and being on the water) and also worked as a psychotherapist. I found the bobbing a little difficult, I wanted to swim. So I started swimming off and coming back like a child on an adventure.

Then I started trying to swim better so joined a group and did a few events, dressed in a wetsuit, a hood, two anoraks and a duvet. Then I did longer events in skins with other swimmers, and then we started chasing the cold to see what that was like. Before I knew it, the gateway drug that was bobbing around in neoprene became 0.3C in Iceland, a couple of ice kilometres and a dozen or more 10km events.

I’m part of a pod of like-minded swimmers. We are less driven by events or challenges now. Mainly we just swim, against the current first so we get a helping hand coming back. That community, gathering as it does around the sea and the physicality of swimming is wholly central to my life. I am told that comes out in the book, it’s not like I was trying to keep it a secret. I think the tone of the novel is established by my relationship with the sea swimming.

Mark’s new book Three Gifts (2023) is published by Epoque Press.