A few lessons from 2Swim4Life

This year I took part in my first ever 2Swim4Life event. I wasn’t brave (or foolhardy) enough to take on the entire 24 mile swim, nor have I done enough training, but I entered as part of a three-person relay with Graeme Schlachter and Laura James, who I swim with at Teddington Masters. This reduced the swim to a more manageable eight miles and allowed more time to recover and warm up between swims and, importantly, observe other swimmers.

For those unfamiliar with the format, the aim is to swim a mile every hour for 24 hours. You have to stop after each mile and you can’t start your next mile until the next hour. The event takes place in the beautiful Guildford Lido, which is a 10-lane 50m pool. The heating is turned on just beforehand, warming the water to around 19 or 20 degrees Celsius. Wetsuits are optional and you can swim any stroke you like (and yes, one team did a medley relay). All swimmers (even those doing relays) are required to have a ‘buddy’, whose job it is to count lengths and ensure their swimmer is properly looked after.

To non-swimmers, this event sounds crazy. You don’t get anywhere and it’s not a recognised swim such as crossing the English Channel, although the distance is longer. Still, this year’s event sold out within a few days and many of the swimmers were repeat offenders who after previous experiences had sworn never to come back. As swimmers know, there is something compelling about plumbing the depths of your physical and mental strengths, and this event does that in buckets.

The simple format disguises the brutality. A mile in 20-degree water: how hard can that be? Then you get to eat, rest, and warm up. What’s the problem?

The fastest swimmers completed each mile in around 22 or 23 minutes, with slower swimmers closer to 40 and the average a shade under 30. That leaves around 30 minutes to get ready to swim again. And that time is crucial.

In the May 2017 issue of Outdoor Swimmer, we looked at some research on cold water swimming from the Extreme Environments Laboratory at Portsmouth University. One thing this showed was that your body temperature drops faster once you leave the water, and this ‘after-drop’ reaches its low point about 20 minutes after you finish swimming and it can take more than an hour to recover to normal.

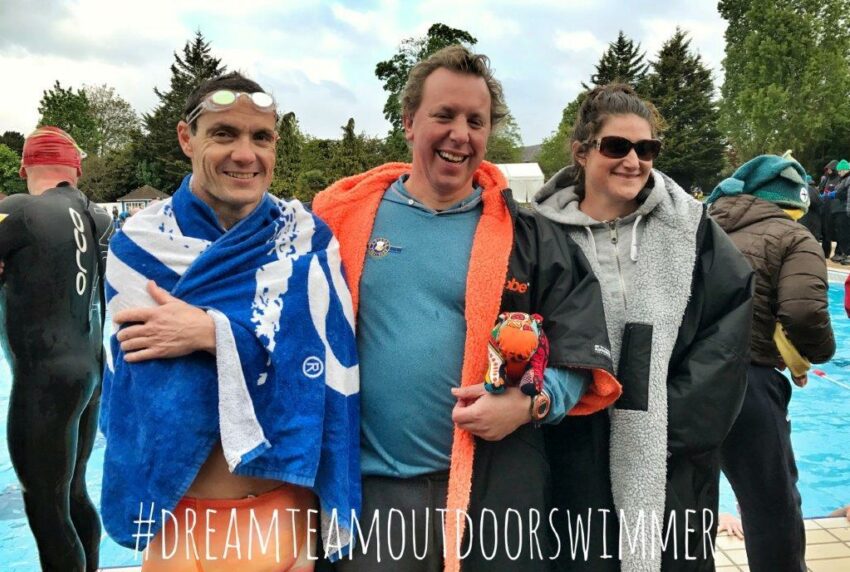

With Laura and Graeme after my final swim

For 24-hour swimmers, this means they will be re-entering the water when their body temperature is already depressed, and the impact is cumulative throughout the swim.

This year we were lucky with the weather during the day as we had glorious sunshine and this helped keep spirits and body temperatures high. But we also had a clear night and the air temperature fell to single digits, and this made rewarming between swims more difficult. I did shifts at midnight, 2am, 5am and 8am and the 2am was particularly hard. Although it was 90 minutes since my previous swim, I still didn’t feel as if I had warmed up, and I was also desperate to sleep. The extra hour between my 2am and 5am swims made a big difference. On top of that, it seems our body temperatures drop slightly at night anyway, as we’d normally be sleeping, so keeping warm throughout this event is a massive challenge.

Other factors that make this swim difficult are sleep deprivation, the distance (several people pulled out with injured shoulders) and gut issues.

So how did the successful swimmers do it, and what can we learn from them?

1. It’s a team effort

Your buddy is crucial. The swimmer needs to maximise recovery time and minimise distractions. A good buddy makes sure the swimmer is quickly changed, wrapped up and fed. Leave your buddy to update social media and watch the clock to make sure you’re at the start of each swim on time. Your job is to swim. Your buddy also provides encouragement and is there to provide support if you push yourself too far. Some swimmers had more than one buddy working in shifts.

Your wider team also consists of the people you signed up with and who swim in your lane. Many swimmers worked together in their lanes to pace and encourage each other. If you’re swimming a relay, make sure you look after the other people in your lane.

2. Have a system

Successful swimmers were efficient not just in the water but also between swims. Clothes were laid out neatly ready to go back on quickly, food was pre-planned and easy to prepare and eat. At the start of each mile, the swimmer would be ready on time every time, with as much protection from the elements as possible until the final moment. There was no fuss, just a quiet determination to get the job done.

What swimmers do at 3am

3. Speed is less important than you might think

Faster swimmers would appear to have an advantage on a swim like this: they get more time to recover and warm up between swims. However, you should never under-estimate the dogged determination of slower swimmers. While faster swimmers crash and burn, slower swimmers conserve their resources and keep going. Your swimming speed is just one of many attributes that will determine whether or not you will succeed in this event – don’t over-rate it.

4. Coping with the temperature is not just about body fat

The research mentioned above also showed that the rate a swimmer loses heat is related to two things: a body shape factor (primarily, how much fat you’re carrying) and how hard you’re working. A larger person with more body fat will stay warm for longer than a small skinny one. However, unlike long distance continuous swims, 2Swim4Life requires repeated immersion and re-warming. I saw several slender people complete the distance without resorting to wetsuits. There is therefore something more going on than body fat helping them keep warm. Perhaps some people have an ability to warm up faster than others? And maybe this is something that can be trained. Or did they just have a great system in place to ensure heat was conserved as well as possible between swims?

5. Be prepared to change your strategy if it’s not working out

If you’re struggling with the cold, put on a wetsuit. 2Swim4Life isn’t the English Channel and wetsuit swimming is allowed. I saw several swimmers who decided it was better to finish in a wetsuit than to withdraw with hypothermia. With only eight swims to do instead of 24 I didn’t need a wetsuit but I did decide to risk exhaustion by swimming faster in the night as that left me less cold after each swim.

6. Know when it’s time to quit

It’s just a swim. It’s not worth a long-term injury or hypothermia. You need to recognise the difference between tired shoulders and damaged ones. You need to be attuned to the difference between feeling uncomfortably and dangerously cold. Most importantly, you need a buddy to point these things out to you if you’re too stubborn (or hypothermic) to realise yourself. Your buddy needs to be your biggest cheerleader, until they need to make you stop.

7. Remember to smile

At some point you need to recognise and accept the absurdity of what you’re doing. While strip changing in front of strangers and leaping in to cool water in the middle of the night seems totally natural and normal when you’re surrounded by lots of other people doing the same thing, it’s really not. This is unusual behaviour. You might as well laugh about it.

Many thanks to Katia Vastiau for being my buddy at 2Swim4Life 2017 and for all the photography