Mother courage: the story behind new film Vindication Swim

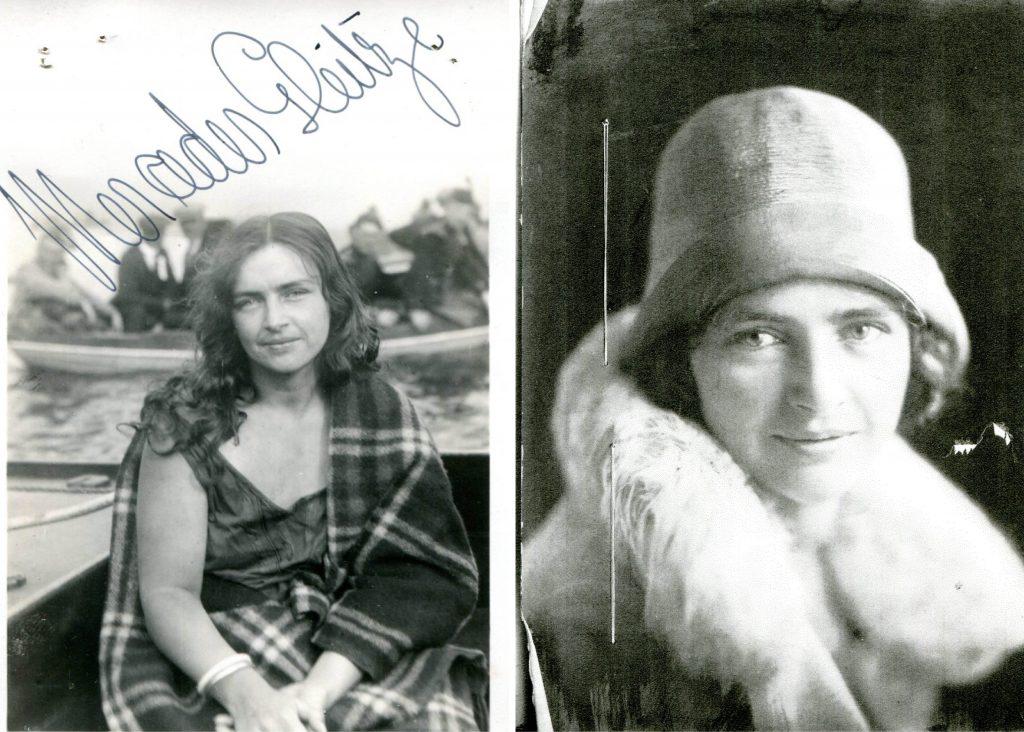

Swimming legend Mercedes Gleitze was the first British woman to swim the English Channel. She was also a pioneer in other ways: an independent, working class woman who swam to fight poverty. In the run up to a new film of her life, Vindication Swim, Mercedes’ daughter Doloranda Pember shares the story behind her pioneering feats of endurance

This article was first published in H2Open (the previous name for Outdoor Swimmer) in April 2016.

Mercedes Gleitze was a pioneer long distance swimmer who, in 1927, became the first British woman to swim across the English Channel.

Her background was one of working class, immigrant status. During the last decade of the 19th century her parents travelled from Germany to England to look for work, and they settled in Brighton, where Mercedes and her two elder sisters were born. This is where Mercedes learnt to swim when she was 10 years old.

After World War I, the family resettled in Germany. In 1921, when she came of age, Mercedes returned to England, the country of her birth. She found a job as a typist in London, rented a flat, and became one of the ‘new women’ of that era, living an independent life of her own choosing.

But she wanted more from life. She had two ambitions: to become a long distance swimmer; and to help the unemployed homeless people sleeping rough in London. She believed that if she became a professional swimmer she might earn enough in prize money to set up a charity to combat poverty.

Training to swim the Channel

Mercedes made the English Channel crossing her first goal. She used the River Thames (a tidal river) to train in on Sundays, and during her summer vacation she travelled to Folkestone to acclimatise to sea conditions.

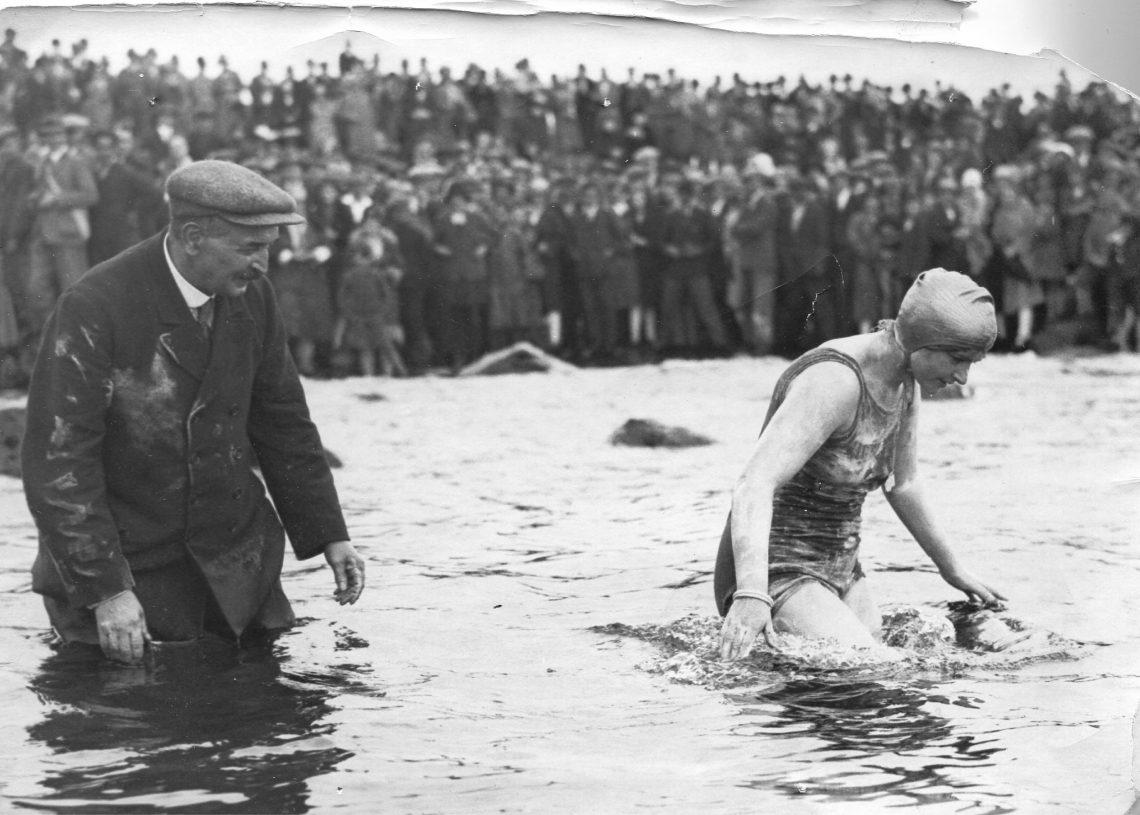

It took her a while, but on 7 October 1927, at her eighth formal attempt, Mercedes swam across a fog-bound English Channel from Cap Gris Nez to St Margaret’s Bay in 15 hours 15 minutes. The beach at St Margaret’s Bay was also heavily shrouded in fog and the only witnesses to the landing were her accompanying crew.

A few days later, however, another Channel aspirant, Dorothy Logan, hoaxed the nation into thinking she too had completed the swim. When suspicions were aroused by both the French and English authorities, Dr Logan was challenged and confessed, claiming that she and her partner, Horace Carey, had perpetrated the fraud in order to highlight the fact that – as she put it – “anyone can say they have swum the Channel”. But by so doing she sullied the reputations of all those who had genuinely completed the crossing.

A vindication swim

In response to the slight cast upon her, Mercedes retorted: “All right, I will do it again. The best way to restore the prestige of British female Channel swimmers in the eyes of the world would be for me to make another Channel swim, which I will do at the next neap tide. My conscience is clear, but I want to repeat my performance in the presence of all the witnesses I can get.”

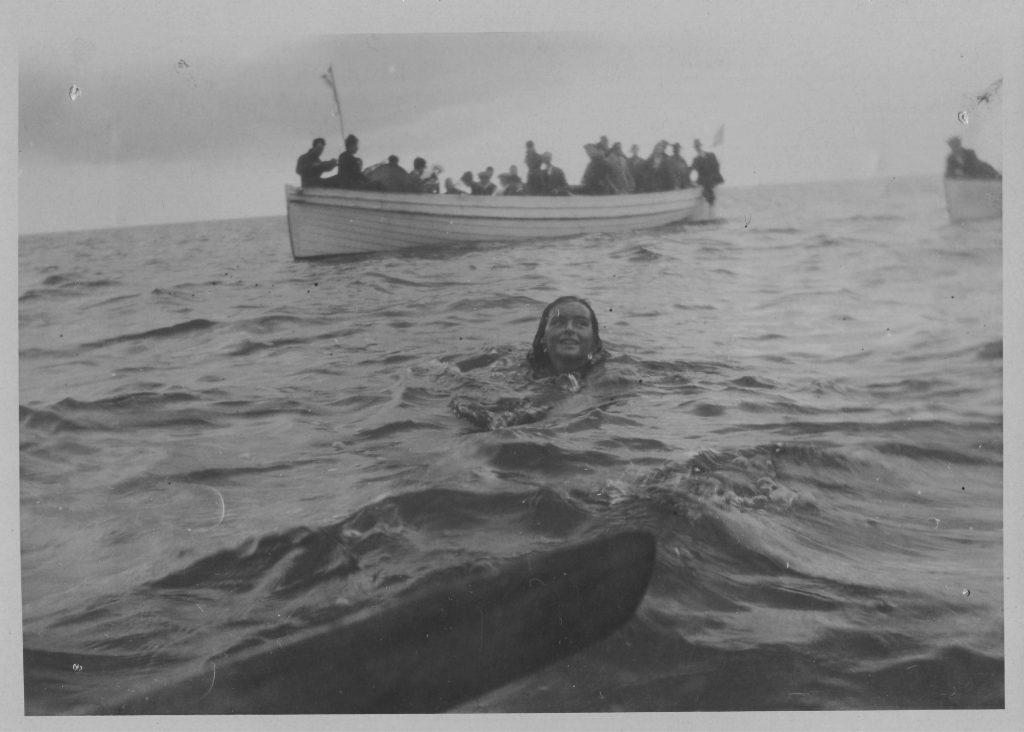

“When Mercedes saw the ladder being let down from the support boat she swam away and had to be chased. A twisted towel was thrown over her head and underneath her arms, and after a struggle and protests from her to “let me go on”, her trainer and pilot pulled her aboard.”

The ‘Vindication Swim’ took place on 21 October, and was widely covered by the world’s press. But it was too late in the season. The sea temperature was 12 degrees Celsius and Mercedes was suffering from a chest cold she developed after her successful crossing two weeks earlier. After ten and a half hours the Vindication Swim was abandoned on the advice of doctors. At this point, she had been battling for three hours against an ebb tide and was on the verge of unconsciousness. When Mercedes saw the ladder being let down from the support boat she swam away and had to be chased. A twisted towel was thrown over her head and underneath her arms, and after a struggle and protests from her to “let me go on”, her trainer and pilot pulled her aboard. She was eight miles from Dover.

However, it was subsequently acknowledged by the newly formed Channel Swimming Association that Mercedes had exonerated herself, and her record as the first British woman to swim the English Channel stood.

Challenging the perception of women

At this point she decided to give up office work and make a living out of sea swimming. It was a high risk decision: she didn’t have any financial backing, just her own savings to fall back on.

Unlike today’s sporting celebrities, she didn’t have a manager to organise her career. She had to navigate her way through a man’s world, not only smashing the sporting glass ceiling, but developing skills as a businesswoman in order to negotiate swimming contracts.

Hers was an extreme sport. She tried for the maximum the human body could achieve. By doing so, she pushed back the boundaries of physical endurance, especially for women. During her six-month tour of South Africa in 1932, she performed all of her swims while pregnant. She gave birth to her first child on her return to England just three months after the end of the tour. This was a further example of Mercedes breaking through existing prejudices and challenging the perception of women as fragile human beings.

“Swimming is a beautiful thing”

Mercedes wasn’t possessive about her sporting talent. She encouraged others to master open water swimming. In her 1930 Diary of New Zealand Tour she wrote:

“Sea swimming is a beautiful thing, in fact an art – an art whose mistress should be not the few, but the many, for does not the sea and its dangers cross the paths of thousands? Nay, millions! What could possibly speak more for man’s prowess as an athlete than the ability to master earth’s most abundant, most powerful element – water, no matter what its mood.”

And when performing her endurance swims in front of thousands of spectators at corporation pools, she promoted the art of swimming to a wide audience of city-dwellers, while at the same time publicly demonstrating to women and girls that it was within them to be physically strong.

She remained true to her swimming aspirations

In 1934, already with one child and pregnant with a second, Mercedes disappeared from the public gaze, and settled down to become a housewife and mother. A few years after her third child was born, she was incapacitated by an inherited blood circulation disorder, and, to a lesser degree, arthritis in her knees.

After her retirement Mercedes deliberately shunned publicity, and as the years went by her exploits were eventually forgotten by the public. Her children knew, of course, that their mother had performed major swims in her youth, but it was only after her death in 1981, when they inherited photographs, letters, witness reports and newspaper cuttings stored away in her attic, that they realised what a major sporting icon she had been.

During her 10-year career, Mercedes remained true both to her swimming aspirations and to her desire to help destitute people. Her pioneering open water swims are numerous and well documented (English Channel, Strait of Gibraltar, Hellespont, Sea of Marmara, Firth of Forth, The Wash, Lough Neagh, Lough Foyle, Galway Bay, Cape Town to Robben Island and back, and so on) and she set the British record for endurance swimming at 47 hours. Her other legacy was the institution of The Mercedes Gleitze Homes for Destitute Men and Women in the city of Leicester in 1933, when she retired from swimming. The homes were destroyed by enemy action in 1940, but her trust fund is still being used today to help people in poverty.

Doloranda Pember is the daughter of Mercedes Gleitze. Her book In the Wake of Mercedes Gleitze: Open Water Swimming Pioneer (Feb 2019) is out now.

Read Simon’s review of the new film Vindication Swim (2024).

If you buy a product through a link on this page we may receive a commission.