Of strongmen and stunt swimming: a history of alternative swimming achievements

Isn’t a marathon swim hard enough without towing trees, boats full of people, or swimming while shackled?

In October 2018, British strongman Ross Edgley completed a 1,792-mile staged swim around Great Britain. The event, which spanned 157 days, garnered worldwide attention and was intended to “inspire people to get out there and challenge themselves,” Edgley told Red Bull magazine. While this effort added to the fitness expert’s international stardom, it wasn’t his first rodeo – the beefy brunette who had once upon a time been a competitive pool swimmer and water polo player had completed a triathlon in 2016 while lugging a 100-pound tree and a 100-kilometre swim in the Caribbean, also while towing a 100-pound log, in early 2018.

While his feats are impressive in terms of the sheer strength required to complete them, they could also be described as stunts designed to show off his status as a “strongman” – that particular breed of athlete that revels in unconventional challenges that seem exaggeratedly absurd, possibly pointless, and nearly impossible.

But Edgley isn’t the only strongman to find success and a massive following with formidable feats of fortitude away from terra firma. Rather, Edgley follows in the wake of a lengthy history of other stunt swimmers (both male and female) who have achieved accomplishments that might not meet everyone’s definition of “swimming” but are designed to inspire awe and perhaps envy of their superior athletic prowess.

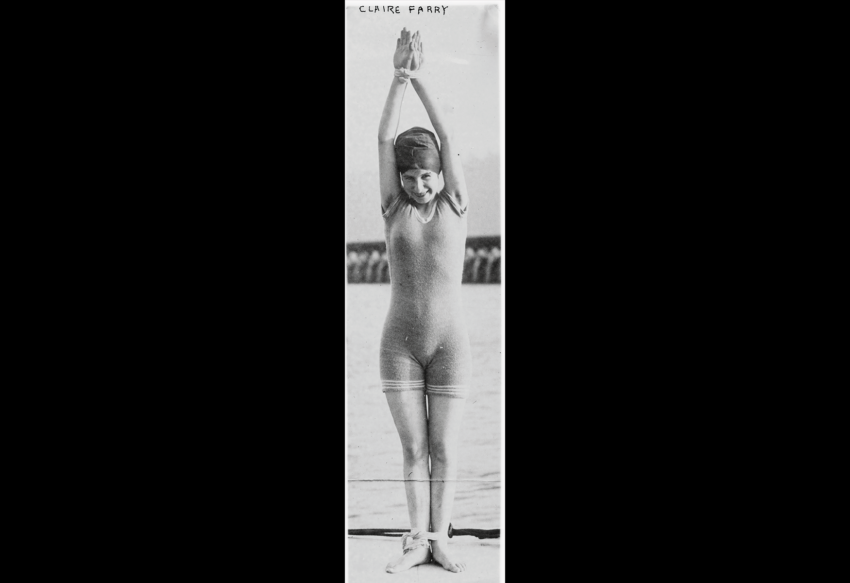

Claire Farry

First among the ‘strongmen’ was a slightly built swimming novice – 15-year-old Claire Farry of Portland, Oregon. A July 1913 Oakland Tribune article reported that Farry, who had only learned to swim 18 months before, made a daring 600-yard swim across the Willamette River with her hands and feet bound with rope. “She did the feat in a little more than fourteen minutes and outdistanced experienced swimmers in her effort, which was the second in five days. The first attempt last week failed when she was almost across, the river being rough at that time.” How exactly did she do it? The Tribune reported that “with her two hands and arms tied together she uses them as the snout of a fish and her hobbled legs act as a fish’s tail as she darts through the water.”

A subsequent 1918 report in the Washington Herald noted that “Miss Farry holds the world record for swimming three and one-half miles among women with her hands and feet tied. This little feat she accomplished in one hour and forty-five minutes.” This report seems to suggest that swimming with hands and feet bound was a recognised event that designated champions, similar to a 200-metre butterfly or the Olympic 10K.

Though Farry made an occasional long-distance splash, the shorter swims were a regular feature of the high-diving star’s repertoire. To boost ticket sales in whichever town she was playing that week, she would often dive from a tall bridge with hands and feet bound and swim to shore where her adoring fans greeted her.

Claire Farry Swam with hands and feet tied together

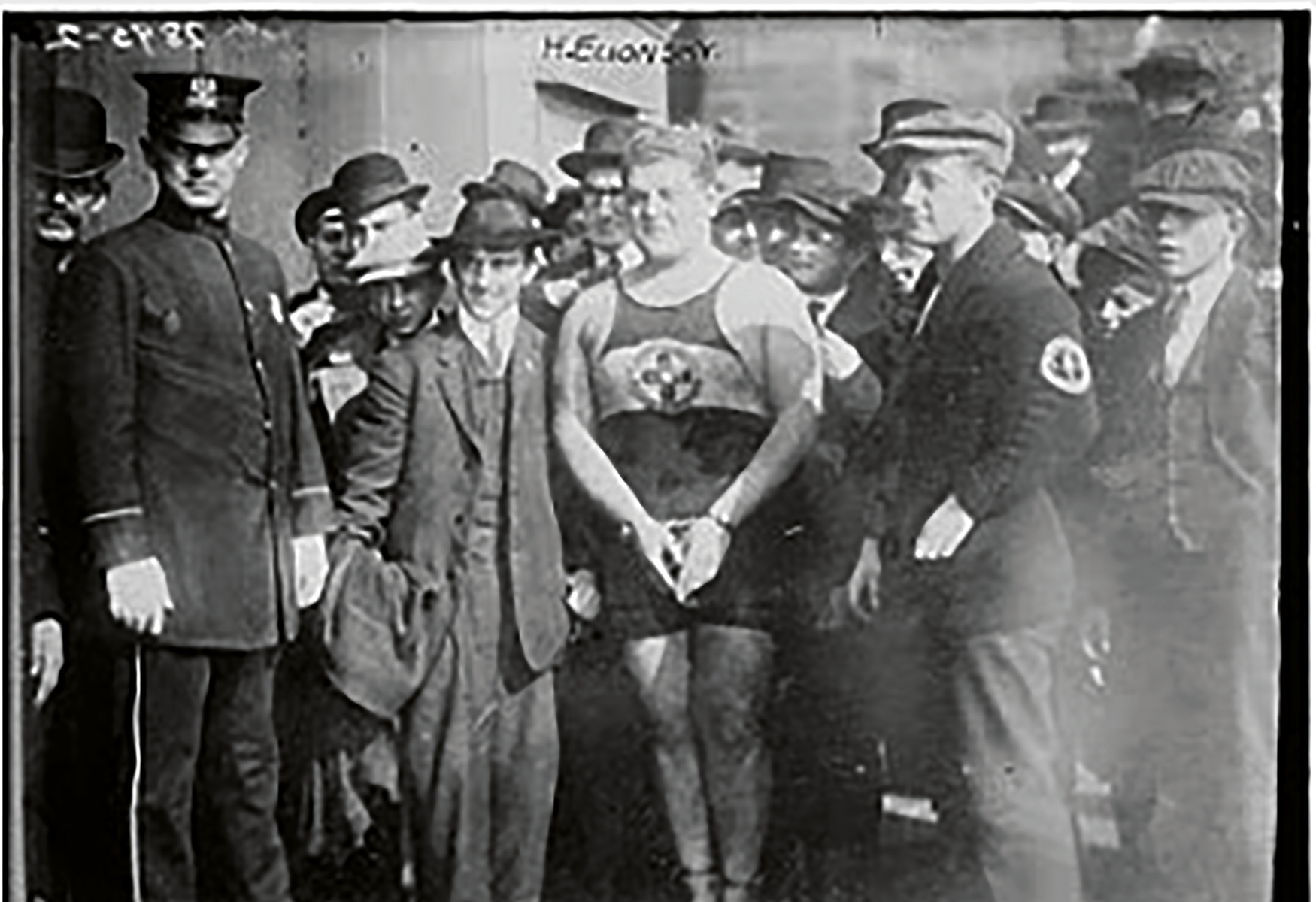

Buster and Ida Elinosky

Around that same innocent time just before World War I began, Henry Elinosky was also staging notable stunt swims. Nicknamed Buster, the stocky New London, Connecticut, teen weighed 265 pounds – one newspaper report said he had “the proportions of a hogshead.” A November 1913 article stated that Elinosky, who’d taken to stunt swimming in his late teens, “swam from the Brooklyn Bridge to Bayridge, a distance of eight miles, with his hands and feet bound and towing a rowboat in which were seven men weighing more than half a ton.” He completed the swim in 3 hours and 11 minutes, which Elinosky suggested was slow because the tide was against him.

So how does one tow a boat with seven men in it while swimming with hands and feet tied to each other? It required a yoke-like contraption, well-suited to Buster’s beast of burden persona. “The boat was attached to Elinosky’s shoulders by a sort of collar arrangement that was not very comfortable after he had gone a few miles.” The chaffing must have been substantial.

In 1914, Elinosky signed up for a head-to-head race against Sam Richards, a top swimmer from Boston, and Charles Durborrow of Philadelphia, in a 17.5-mile race from Manhattan’s Battery to Sandy Hook, New Jersey. According to a pre-swim report in the Norwich Bulletin, Elinosky apparently made clear he wanted a bigger challenge. “Elinosky thinks the course too short. He is trying to convince the authorities that the long distance championship should go to the swimmer who can cover the greatest distance. He wants to swim from the Battery to Sandy Hook in two tides, return to the Battery again, and then take another tide to Coney Island, covering in all about 70 miles and taking about 48 hours to accomplish it.” (It’s unclear whether Elinosky ever did pull off such a feat, though another report from 1921 indicates he set a record with a 65-mile swim in New York waters in 1914. Details of that event remain scant.)

In perhaps his most attention-grabbing swim, Elinosky didn’t do much swimming at all. Rather, his sister, Ida, who was listed as having been 17 at the time and weighing a mere 135 pounds, attempted to swim down the Hudson River from 59th Street to the Battery with big brother Buster strapped to her back. An 18 August 1916 report about the so-called “freak swim” announced it was a failure, through no fault of the plucky breaststroker’s.

“She might have made the trip, despite a stiff half-gale and choppy waves, if all had gone right with her escort party. But at Charlton Street, after more than two miles of the voyage had been completed, it looked as though the Mary M., a motorboat carrying observers and photographers was going to the bottom, and the expedition was called off. Everyone was saved, however, and nothing was lost except Miss Elinosky’s labor.” Ida is best known as being the first woman to swim the 28.5 miles around Manhattan Island, which she did later that same summer in 11 hours and 35 minutes, becoming the first woman and second person to do so.

Henry Elinosky – a stunt swimmer with “the proportions of a hogshead”

JACK LALANNE

Perhaps the most famous of the stunt swimmers was fitness icon Jack LaLanne. The proverbial 98-pound weakling turned strongman, LaLanne founded the first modern gym in Oakland, California, and sparked a fitness revolution that endures today. With his signature phrase “exercise is king, nutrition is queen, put them together and you’ve got a kingdom,” he eventually found his way to television in the 1950s with The Jack LaLanne Show that ran until 1985, making it the longest-running television exercise programme.

In the latter half of his fitness career, America’s godfather of fitness took a shine to long-distance open water “swimming,” beginning with a 1954 underwater swim the length of the Golden Gate Bridge while carrying 140 pounds of equipment. In 1955, he completed a mile-plus solo crossing from Alcatraz Island to Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco while handcuffed. Two years later at the age of 43, he swam 1.6 kilometres across the Golden Gate Channel while towing a 2,500-pound cabin cruiser. (The currents pushed him around a good bit, so this event is sometimes listed as having been a 6.5-mile effort.) To celebrate his 60th birthday in 1974, he repeated his 1955 Alcatraz stunt but added a 1,000-pound boat and shackles just for fun. (Some reports noted he was loosely tied and had some use of arms and legs.) The following year, he repeated his underwater Golden Gate Bridge stunt, this time handcuffed and towing a 1,000-pound boat.

In 1976, to help celebrate America’s bicentennial, he completed a one-mile swim shackled and handcuffed while towing 13 boats (to symbolise the 13 original colonies) with 76 people aboard. He followed that stunt three years later with a swim across Lake Ashinoko in Japan where he towed 65 boats loaded with 6,500 pounds of wood pulp. In 1980, at age 66, he reportedly towed 10 boats carrying 77 people for over a mile in less than an hour in North Miami, Florida.

At age 70, LaLanne upped the ante, pulling 70 boats laden with 70 people across Long Beach Harbor while handcuffed and shackled. Upon completing the swim, LaLanne said: “I feel as cold as a witch’s heart. I can’t believe this has happened. It was a big dream.” The two-hour effort covered over a mile in water that was reportedly 59 degrees F (15 C).

So why did he do it? As much to showcase his robust health and swimming prowess as to market his name, his various fitness inventions and training programmes, and to help inspire others to end their processedfood addictions and couch-potato lifestyles. It seems, too, that LaLanne was having quite a good time in challenging himself to pull off these incredible feats of strength and endurance in the medium of water, where most people wouldn’t have felt comfortable duplicating his efforts.

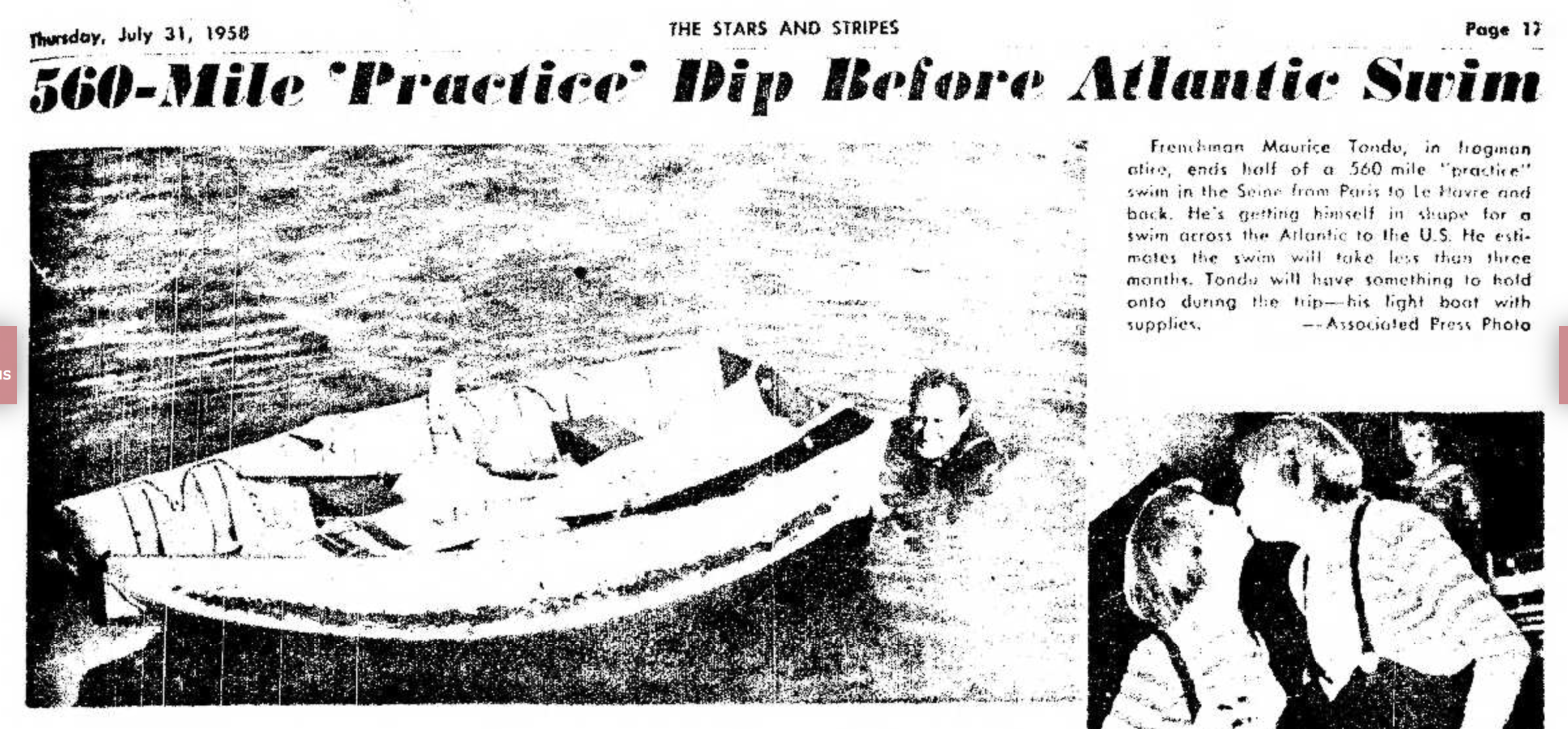

Maurice Tondu

While some stunts inspire awe, others might be classified as ill-advised at best. According to a 29 April 1958 article in the Boston Globe, a 35-year-old Parisian named Maurice Tondu announced his intention to “swim” from Dakar in West Africa to Martinique in the West Indies. The report noted that “he will ‘swim’ the Atlantic Ocean alone with a special dinghy on which he will rest the upper part of his body.” His legs were to be “enclosed in rubber tights. The dinghy will hold his food and belongings.” He hoped to complete the swim “for ‘mainly scientific reasons,’” the Globe reported.

In a dispatch he filed from Paris in June 1958, columnist Art Buchwald reported more detail about Tondu’s attempt, which by then had been refined to follow a 2,500-mile route from the Cape Verde islands off the coast of West Africa to the Antilles islands. Tondu, an accountant by occupation, expected the journey would take just 70 days to complete. “Mr. Tondu will swim four hours in the morning and four hours in the evening, pushing the dinghy and paddling with his feet. The rest of the time he will spend on the dinghy eating, sleeping, and studying the problem.” The problem, indeed.

Tondu insisted that the swim was “not a publicity stunt. I’m interested in the physiological and sociological effects of someone trying to swim the Atlantic. I hope the results of my trip will help in the study of survival at sea and I have certain theories I wish to prove.” He said he would haul 120 litres of water in his dinghy and subsist on “concentrated foods and vitamins.” Although the odds of Tondu reaching the Antilles were exceedingly slim, he was confident he could do it and suggested that when he did, he would likely plan to continue on to Florida.

The press reported on a few of Tondu’s training swims in preparation for the big event, including a weeklong, 280-mile journey down the Seine in Paris. Perhaps not surprisingly, the next media report about Tondu, published 23 October 1958 by Reuters noted that the Frenchman had “not been heard from since setting out last weekend to swim the Mediterranean from France to Tunisia, pushing a rubber raft loaded with food and water supplies.” In a training swim that apparently didn’t go right, it seems Tondu was lost at sea and never made it to the starting line of his Atlantic Ocean quest.

Tondu swam with his legs enclosed in rubber tights

Reading about his swim some 60 years later, it’s easy to dismiss Tondu’s goal as selfdestructive folly. But in the context of that historical moment, just five years after adventurer Edmund Hillary and his guide Tenzing Norgay had summited Mount Everest, Tondu’s undertaking may not have seemed all that outrageous and illconceived. Looking back, we might say Tondu’s attempt was crazy or absurd, but his efforts stand as evidence that in the moment, the line between strategic stunt and sound judgement can sometimes get a little blurry.

Webb's legacy?

The same was true for Captain Matthew Webb. Though he’s widely revered today for becoming the first person to swim the English Channel and fathering the sport of marathon swimming, in 1875 when he completed that first crossing, his swim might have been classified as an impossible strongman stunt. It’s also worth pointing out that he lost his life while attempting what many called a suicidal swim across the Niagara River whirlpool rapids at the base of Niagara Falls on 24 July 1883. At stake was $2,000, but Webb drowned minutes after stepping off the boat for the treacherous attempt. His battered body washed up downstream four days later, still clad in the same red trunks he’d worn across the Channel.

If we can take a lesson from these departed daredevils, then perhaps it is that, in swimming, as in life, we should approach risky endeavours with a mix of enthusiasm and caution. After all, it doesn’t matter how many likes or follows a swimmer receives online if the stunt ends tragically.