Seeking the sacred

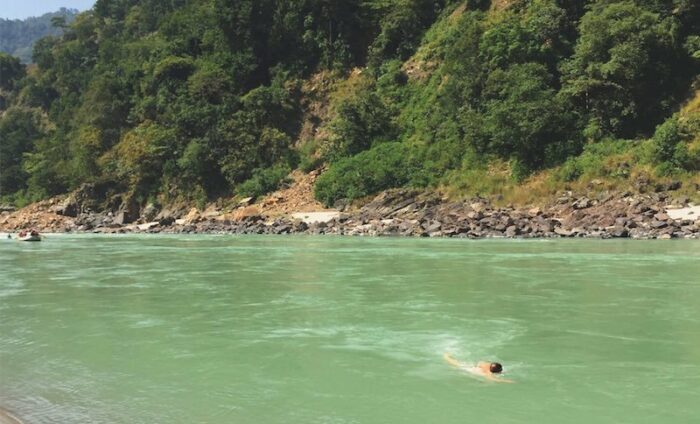

Patrick Scott swims in the volatile waters of India’s holy river Ganges

I was pulling hard against the current of the jade-tinted Ganges in northern India in the foothills of the Himalayas, remaining in a fixed spot about 10 metres from shore, as if swimming against jet streams in an endless pool.

I kept my bearings by aligning my freestyle with a boulder on the rocky shore. Three strokes. Breathe right. Scan the wide, swift-moving sheets of emerald water and the deep green, forested mountainside climbing up into the blue sky. Three strokes. Breathe left. Good, there’s the boulder, surrounded by acres of beige stones embedded in glittering sand.

This swim, in many ways, was divine.

I was immersed not only in one of the world’s iconic rivers, in the enchanting mountain town of Rishikesh, but in a body of water that Hindus hold as sacred, the manifestation on earth of the goddess Ganga.

They believe that she washes away their sins when they bathe in her, and that she helps free them from the cycle of rebirth when their burned remains are scattered into her.

My thoughts skittered from these mystical qualities to others, which an Indian swami and his American yogini deputy shared with me the night before. The river contains millennia of prayers and thoughts of peace from devotees at its banks, they told me. As the water climbs the steep valley each rainy season, it absorbs the healing properties of herbs and plants. And, she said, if you can tune out the world and listen to the universe, you can hear the sacred sound of “Om” through the water.

So I went deeper to listen, switching to butterfly. Popping up and ducking back in, staying under with a double kick, trying to be in the present, seeking the sacred.

A slight problem with this approach is that staying under for a few seconds each time meant that the boulder I was spotting was quickly out of view and I was heading downriver.

This being the only stretch of the 2,500-kilometre Ganges with rapids, the river is volatile and incredibly strong. Luckily, I was on a flat section where I could get back to shore soon enough by sprinting against the flow.

Later in the week, it wouldn’t be so easy.

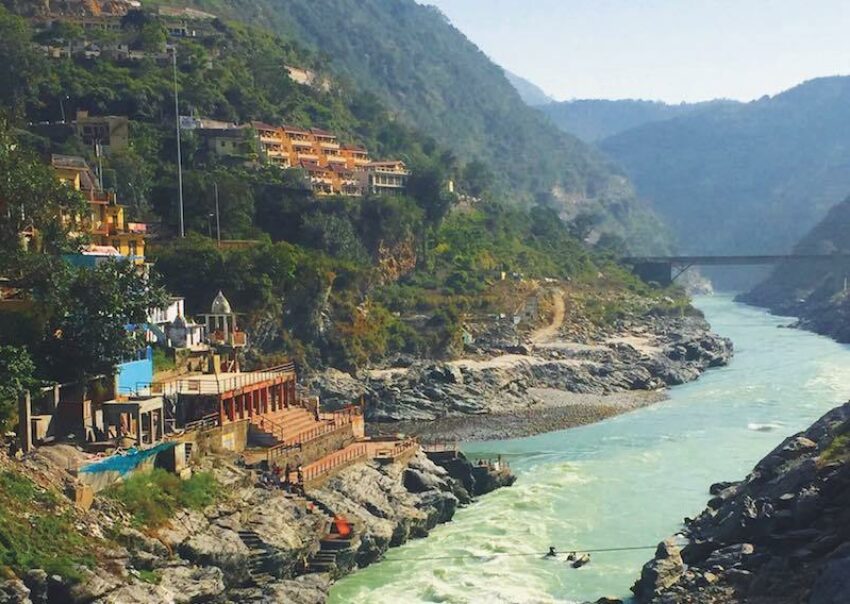

Rishikesh in northern India

Life, movement and colour

We were in Rishikesh, about a six-hour drive north of Delhi, because my wife had chosen this reputed yoga capital of the world for her month-long yoga teacher training and I was reporting a story on whitewater rafting on the river.

You probably know Rishikesh as the place where The Beatles sought enlightenment from Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in 1968 and wrote a number of songs for the White Album. In the decades since, mushrooming yoga ashrams, guesthouses, cafes, shops, and rafting and trekking companies have cluttered the hills in a planner’s nightmare. Life, movement and colour are bursting out all over.

On both sides of town, divided by the river, the narrow lanes and switchback roads are a constant parade of tourists in pyjama pants, Indians in brightly coloured saris and holy men in orange or black robes. From the two narrow suspension bridges, as you dodge dung-dropping cows and mischievous monkeys, you can see Disneyesque temples on the banks, and intermittent fleets of blue or red rafts ending trips down river.

Swimming is not a thing here. Contact with the water mainly involves tourists (the vast majority of them Indian) hopping into the river from a raft in a lifejacket and bobbing downstream, or devotees wading into the shallows for a more concentrated spiritual plunge. But for open-water swimmers it can be ideal.

This section of the Ganges is what rafting guides call pool and drop, about 35 kilometres of mostly smooth and powerful stretches that descend into 11 churning sets of Class 2-4 rapids. I swam in the pools.

The river here is relatively clean and clear, being close to its origins in the snow-capped peaks of the Himalayas. But it has a milky-green tint, so you can’t see more than a foot or two deep. The beauty is in the rhythm of the flow, the water racing and swirling and hopping over the boulders that carpet the riverbed, and in the majesty of the forested hills surrounding the winding course.

Pitched and slung

For the first swim, my Airbnb host told me he had the perfect beach. Halfway there, he stopped his motorcycle at a low stone wall to point out the funeral pyre on the shore below. Small groups of people about 200 metres away sat amid boulders as a log-stacked fire blazed orange and white against the rushing emerald water. I wondered what other remains might be coming down the river when I got in.

Soon we were at the beach, about 8 kilometres upstream from the Laxman Jhula bridge, behind a thicket of trees and bushes. The sand was a remarkably fine mixture of white and black, glittering with flecks of silver and gold. Rafts and kayaks drifted quickly past and I walked onto the steep drop-off at the edge and shoved into the bracingly cold water, about 15 degrees. It felt slightly sulphurous but didn’t taste so, and the current was nicely matched with my 1:30 per 100m pace, as I aimed for a little island of rocks ahead.

On Sundays, my wife had the day free and on our first reunion we walked a couple of miles upriver from the town along the winding road hemming the riverbank. We arrived at a steep path through the trees that led to a narrow bank of sand where the river was flat and about 60 metres wide. Directly across was one of the many Ganges ghats — stone steps leading into the river from a temple or ashram. I judged that if I dove in and sprinted upriver at a 45-degree angle, the current and my trajectory would put me right on the steps.

In most rivers, lakes or even seas, wild swimmers generally know how the water is going to move and feel. But here, because it’s so hydraulic, you’re pitched and slung this way and that as you try to catch the water, your arms flailing and legs scissoring through pockets of turbulence. I wound up below the steps, but still on the other side, clutching onto a cropping of rocks. As I pulled up out of the water, a swarm of black and chartreuse butterflies greeted me. They flitted around as I scaled along the stony embankment to the steps. After a breather, I dove in and scrambled back over to the sandy bank.

The only stretch of the 2,500-kilometre Ganges with rapids

Into the whirlpool

On one of my last swims, I was staying at Atali Ganga, a 35-minute drive upriver from Rishikesh with stone and timber villas terraced on a mountainside overlooking the river. They didn’t allow swimming without a lifejacket at their beach. So I walked 15 minutes up the road to a trail through the forest down to a secluded stretch of glimmering sand and smooth round rocks.

The river was wide and swift. About 150 metres downstream, the water hurtled into a wall of rock jutting out from the valley, sending the course veering left around the bend. There were no rafts in site as I swam freestyle close to shore, using my backpack to orient my position. But soon I was drifting toward the middle. By the time I realised, I was about 40 metres from the shore, and the current was pulling me downriver toward the cliff.

I tried to sprint to the bank but was pulled into a large whirlpool, created as the flow rushed into the rock wall and backtracked around large stone slabs sticking out of the water. It wasn’t a voracious and steep vortex that would instantly suck me down; more like a merry-go-round I couldn’t get off. I tried to plow and kick my fastest toward the shore, swimming just below the protruding slabs, but the power of the river kept sucking me back in.

I had learned from the river guides that one way out was to dive into the middle, get sucked into a chute traveling downstream and eventually pop up. But before I resorted to that, I tried to rest as I was orbiting the eddy.

Still no rafts in site. If I couldn’t make it to shore, maybe I could break out heading downriver toward the cliff. I charged ahead one more time and escaped. I stroked furiously toward the cliff-face closest to shore and reached the edge of the flow that was coursing into the rock wall and ricocheting upstream. I caught that reverse flow and sprinted toward the riverbank, and the current released me in the shallows. My heart racing, I crawled up into the round rocks, kissed the warm sand and gave thanks to Mother Ganga.

Patrick Scott is a freelance travel writer based in Ho Chi Minh City whose iconic-river swims include the Thames, Hudson, Nile and Ganges, and maybe soon the Mekong. He chronicles his adventures in publications including The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. You can follow him on Instagram @patrickrobertscott and read his stories at www.patrickrobertscott.com