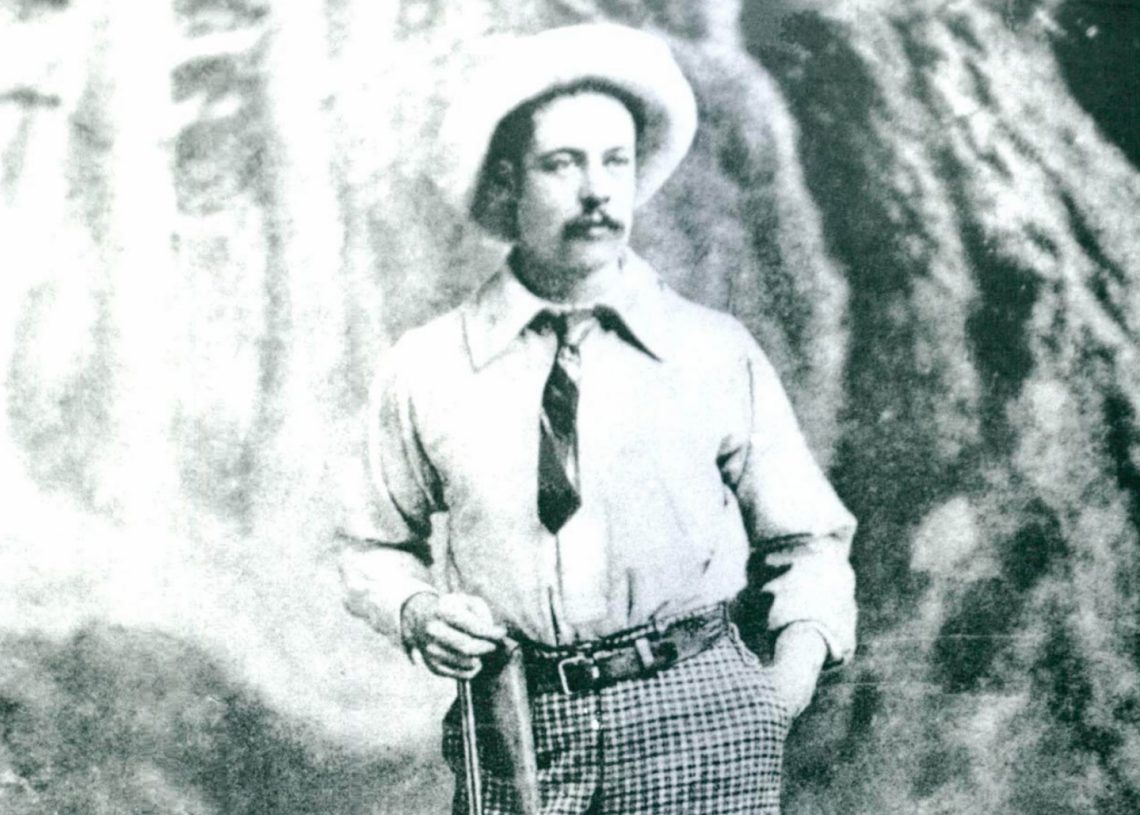

The Great Sportsman: William Henry Grenfell

The 1st Baron Desborough, William Henry Grenfell left a lasting legacy in open water and Olympic circles. Elaine K Howley discovers the story behind the Oxford rower, pioneering Rocky Mountain rambler and daring Niagara Falls dipper who went on to become a swimming legend.

Across the lengthy history of Oxford vs Cambridge, one single rowing race stands out from the others.