The Lady Champion Aquatic

From Les Enfants Poissons to matriarch of natation, Agnes Beckwith inspired a generation of female swimmer

Born on 24 August 1861 in Lambeth, Agnes Alice Beckwith didn’t need much time to become a swimming superstar. Her father, Frederick Edward Beckwith, was a noted swimmer and swimming teacher, who listed his profession in the 1871 census as “professor of swimming.” At the time, this was a title claimed by a handful of swimming instructors and performers across the English-speaking world. A celebrated sportsman who also staged elaborate demonstrations of swimming for enthralled Victorian-era audiences, Frederick naturally brought his children into the act with him, and by 1865, his four-year-old daughter Agnes was swimming professionally in a stage act Frederick dubbed the “Beckwith Frogs.”

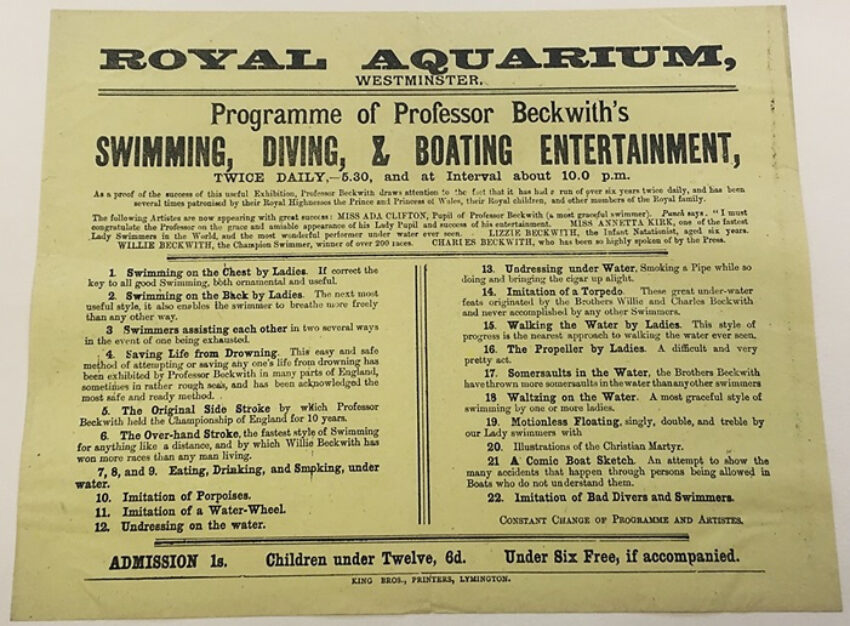

Alongside her siblings Lizzie, Willie and Charles, Agnes grew up performing regularly at the Royal Aquarium in London “demonstrating swimming strokes and life saving techniques as well as preforming aquatic stunts such as smoking, drinking milk, and eating sponge cakes underwater,” the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography reports. A Royal Aquarium theatre programme from 1884 also lists “imitation of porpoises,” somersaults and “a comic boat sketch, an attempt to show the many accidents that happen through persons being allowed in Boats who do not understand them,” as being segments of the 22-part act that concluded with an “imitation of bad divers and swimmers.” In another act, dubbed Les Enfants Poissons, Beckwith performed with her younger brother and showed that swimming and water safety could be child’s play.

In his 2015 paper, “From Lambeth to Niagara: Imitation and Innovation among Female Natationists,” Dave Day, professor of sports history at Manchester Metropolitan University writes that “of all the aquatic activities, ornamental swimming was considered the most appropriate for female natationists and aquatic displays utilising swimming baths and glass tanks in aquaria, circuses and music halls provided extensive opportunities for swimming entrepreneurs…. Wherever she performed, Agnes was consistently described as ‘a veritable mermaid’, swimming, floating, diving and turning somersaults through hoops, as well as kissing her hand to spectators in ‘the most bewitching style’.”

It might seem absurd to us now, to watch someone else demonstrate a perfect breaststroke on stage, but in the mid-19th century, very few people could swim, and those who had this special skill often made a good living showing off their talents in aquarium shows, beach demonstrations, and later, vaudeville performances. And thus, the family Beckwith made quite a name for themselves, performing to packed houses across the UK, North America and Europe.

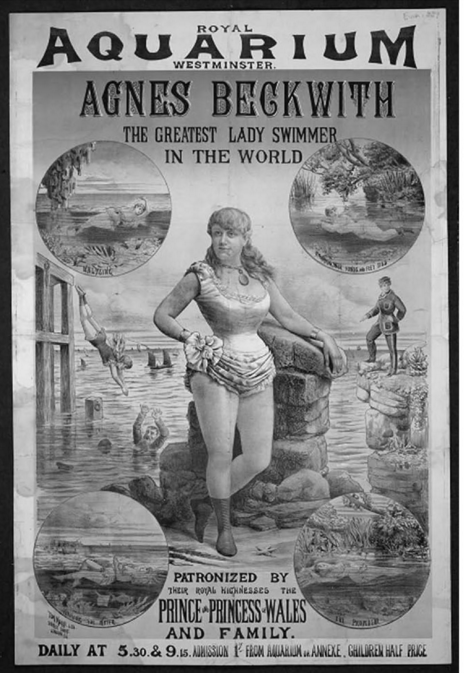

But Beckwith’s fame would eventually overspill decorum’s dictates and eclipse the rest of her family’s notoriety. By 1885, she was headlining shows under the title “The Greatest Lady Swimmer in the World,” perhaps a complement to her father who was often billed as “The Greatest Swimmer in the World.” Agnes Beckwith was Victorian England’s swimming “It” girl, and her star would continue to rise for some time, buoyed by salt water and her father’s ambition for her career.

A Star Is Born

It all started with a little swim in the Thames, staged to capitalise on the media frenzy stirred up by Captain Matthew Webb’s swim across the English Channel, incidentally completed on Beckwith’s 14th birthday. “Partly to ‘puff up’ himself and Agnes, Professor Beckwith took advantage of the interest generated by Webb’s success and embarked on a series of endurance swims featuring his daughter, beginning on 1 September 1875 with the 14-year-old swimming five miles in the Thames from London Bridge to Greenwich,” Day writes.

At the time, Beckwith’s costume might have seemed revolutionary to onlookers who were likely more accustomed to seeing Victorian women wear voluminous dresses with petticoats to the seaside. Victoriana magazine describes these garments as covering “most of the female figure,” with “long bloomers… made from a heavy flannel fabric which would surely weight down the swimmer.” By comparison, Beckwith’s performance outfit looked strikingly like a modern swimsuit, albeit one better suited to pool-side lounging than competitive swimming. (The flounces, ribbons and bows would surely slow down a speeding swimmer.)

Nevertheless, Beckwith’s costume was far more figure-revealing and practical for her various aquatic pursuits. In her book “Downstream: A History and Celebration of Swimming the River Thames,” Caitlin Davies reports that Beckwith’s costume was a featured component of virtually all reporting made about her endeavours. “Like Annette Kellerman some 30 years later, it was Beckwith’s attire that was of just as much interest, ‘a swimming costume of light rose pink llama [reported elsewhere as lama, lamé, or satin] trimmed with white braid and lace of same colour.’”

The dainty dress stood in stark opposition to the physical achievement the “slim and diminutive” Beckwith had just accomplished at such a tender age. Of the 1-hour-and-7-minute Thames swim, The Guardian newspaper reported “for a powerful man the feat may not be an over difficult one; but it is a test of some endurance for a slight young girl like the performer of yesterday. Miss Beckwith, though only 14 years of age, is, however, no weak or inexperienced swimmer.” The public and the media loved what Beckwith had to offer, and thus, she began staging longer swims and more outrageous feats that always garnered a flurry of press coverage.

A small item in the Saturday, 8 July 1876 edition of Berrow’s Worcester Journal reported on Beckwith’s biggest feat to date, a lengthy swim down the Thames through London. “On Wednesday afternoon Miss Agnes Beckwith, daughter of the well-known swimming master, surpassed all her previous performances by swimming from Chelsea to Greenwich, a distance of ten miles.” The swim took her 2 hours, 46 minutes and 25 seconds, during which time she did not feed or otherwise “take refreshment.” Nevertheless “upon leaving the water Miss Beckwith was comparatively fresh.” While the item doesn’t indicate who or what she was being compared to in that assessment, it does note that “this time has never before been equaled by a lady swimmer, and Miss Beckwith, who is not yet fifteen years of age, deserves great credit for her performance.”

From there, she just kept swimming. An 1880 piece from the Chambers’ Journal, which openly compared the “young damsel” to Webb specifically, characterises Beckwith’s Thames swim as being “clear proof that the weaker sex is strong enough to achieve remarkable results in this art.” In July 1878, the 17-year-old Beckwith swam 20 miles in the Thames and flirted with pursuing an English Channel swim, a desire that was never fulfilled.

The Floating Phenomenon

While long-distance and competitive swimming had its place, Beckwith still had both feet firmly in the world of demonstration-style swimming and one quirky tributary thereof – endurance floating – would only add to her fame.

It all started with a very long day at the Royal Aquarium in 1880. The Chamber Journal reported that “quite recently the London public have been astonished by proofs of the great length of time that persons can remain floating with or without swimming. At the Westminster Aquarium is a large tank constructed for the temporary reception of a live whale. In this tank, Agnes Beckwith remained afloat for thirty hours, without touching ground or sides of the tank, singing a little and occasionally reading a newspaper to pass away the dreary monotony, and taking refreshments handed to her. The water had a strong infusion of salt thrown in it to increase its buoyancy.”

Beckwith’s feat caught Webb’s attention, setting off something of an arms race in the wondrously Victorian pastime of endurance floating. The Journal reports that since Beckwith floated into the record books, “Captain Webb has eclipsed everything else of the kind known. In the recent month of May he remained in the whale tank no less than sixty hours continuously floating all the time, and never touching sides or bottom.” But Beckwith answered with an even longer stunt. She reportedly swam for 100 hours nonconsecutively over 137 hours total in the Aquarium tank. That feat earned her the highly-marketable title of ‘Heroine of the 100 hours’ swim’.

Other women wanted in on the floating phenomenon, too, presumably because it required a little less technical swimming skill but still garnered a lot of press attention. Edith Johnson of England lasted 31 hours in 1880. Lottie Schoemmel, better known for her English Channel attempts, lasted 32 hours in 1928. In 1931, Myrtle Huddleston, of Catalina Channel fame, posted an astonishing 87 hours 48 minutes afloat without assistance in a pool, according to Judith Jenkins George of Depauw University, writing in her paper, “The Fad of North American Women’s Endurance Swimming During the Post-World War I Era.” Even Mercedes Gleitze, the first British woman to swim the Channel competed in endurance floating events, including a 34-hour float at the Ormeau Baths in Belfast in 1928.

Copycats

Endurance floating wasn’t the only feat Beckwith’s efforts inspired other women to copy. Some went so far as to claim familial affiliation by appropriating the Beckwith name for their own commercial ventures. If you come across the names Cora Beckwith or Clara Beckwith in the annals of swimming history, know that they were not actually related to the Beckwith Frogs of Lambeth.

Cora Beckwith was born Cora MacFarland in Maine in 1870 while Clara was actually Clara Sabean, born in 1870 in Nova Scotia. Both concocted false origin stories that linked them to England and the Beckwith family – some people confused Cora and Clara with Agnes herself, a misconception neither woman was quick to correct – and they performed regularly across the US and Canada under these assumed names.

This was perhaps not a shocking turn of events, writes Day, given how swimmingly famous the Beckwiths actually were at the time. “With Agnes as its leading light,” the Beckwith name “became synonymous with female swimming excellence. “Recognising the commercial potential, American natationists Cora MacFarland and Clara Sabean both claimed English origins and appropriated the Beckwith surname, adopted Agnes’s performance routines and made long and successful careers as ‘Champion Lady Swimmer of the World’.

A Champion for Other Ladies

In the end, perhaps Beckwith’s most lasting and important contribution to swimming came in the form of her efforts to teach other women to swim. After her 20-mile Thames swim, Davies reports that “one journalist applauded ‘little Missie Beckwith’s marvelous swim… What girl will now remain ignorant of swimming?’”

Taking this question to heart and following in her father’s footsteps in more than just showmanship, Beckwith became a noted swimming instructor who taught scores of women over the years. She also built a travelling performance around her “Wonderful Troupe of Lady Swimmers.”

“One observer of the [women’s] troupe declared that by their graceful and expert performances they had popularised the art of swimming,” Day writes. “These swimmers pleased everyone who saw them by their charming appearance in their pretty costumes, reinforcing the impression that the appeal of female natationists to many male admirers often had as much to do with their physical appearance as their skill.”

Still, costumes and mores of the era aside, it seems the efforts of the “London Naiad” did much to normalise swimming and make it a safer venture for many women.