The loneliness of the black long distance swimmer

On 25 August 1981, Charles Chapman, AKA Charlie the Tuna, became the first black swimmer to complete a solo crossing of the English Channel. Forty years on, there are still massive barriers to participation and a yawing disparity in participation rates for black and brown people at all levels of swimming.

On August 25, 1875, Captain Matthew Webb became the first person to swim across the English Channel. It was a history-making event of epic proportions and helped birth a new sport – marathon swimming.

Some 51 years later, Gertrude Ederle became the first woman to swim the Channel, also to much fanfare. Her swim launched a new renaissance of marathon swimming around the world, as interest in her success and shattering of the men’s record by more than two hours captured the imagination of millions of people around the world.

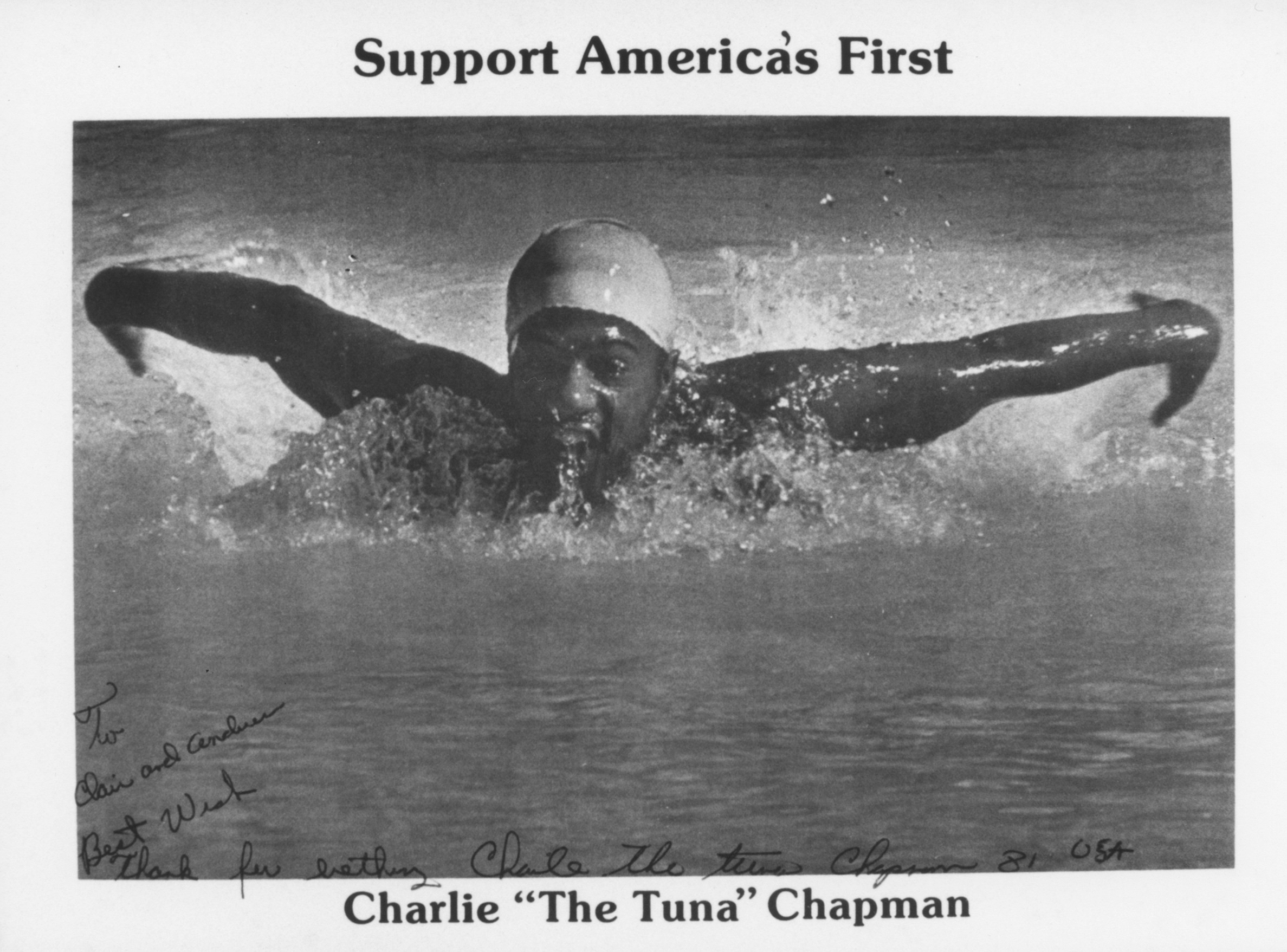

On the 106th anniversary of Webb’s crossing, another first took place in the English Channel. That day, 25 August 1981, the first black American completed a solo crossing of the Channel when Charles Chapman, AKA Charlie the Tuna, of Buffalo, New York, made an impressive crossing in 13 hours and 30 minutes.

Chapman was an early master of butterfly

Becoming the Tuna

Charles Chapman was just 27 years old when he swam to success in the Channel. But he’d been swimming for a long time prior to that. During a four-part interview about his swimming career conducted in San Francisco in 2011 by fellow black marathon swimmer Naji Ali, Chapman joked that “I got started in swimming because they wouldn’t pass me the basketball.”

Chapman learned to swim at age five – his parents insisted that he be water-safe and enrolled him in classes at the local YMCA. Chapman “didn’t start out as the fastest swimmer. But I endured to the end,” he remembered. He also had a supportive family and community that encouraged his love of swimming.

Over time, his diligent effort and love for the sport paid off. He helped his Woodlawn Junior High School win the city championship and went on to Bishop Turner High School where he set a varsity record in the 100-yard butterfly event.

These were the early days of the new, fourth stroke. “The stroke hadn’t been perfected,” Chapman told Ali. “There was none of this smooth stuff we have today. It was the dinosaur age of swimming,” he laughed.

In addition to mastering the new butterfly, Chapman also coped with “serious chlorine burn. These were the ancient days of swimming. But I wouldn’t trade any of those experiences for anything because they’re the things that prepare you for anything. In this swimming business, especially in the marathon business, no matter what the conditions are, you have to be really ready to put it out there.”

After graduating from high school, Chapman visited his track-star sister in Los Angeles, and wound up getting himself a scholarship to swim for the Los Angeles City College team. Around this same time, he read a book by Arden Hills Swim Club coach Sherm Chavoor, the Sacramento-based guru who coached Mark Spitz to glory. Chavoor noted that a black person would certainly become an Olympic swimming champion some day and he wanted the opportunity to work with that individual. Chapman wrote to Chavoor asking for a shot to be that man, and “Sherm gave me a tryout,” Chapman recounted. He made the team and enrolled at Sacramento State University.

Though Chapman acknowledged that he was starting his quest for Olympic glory a bit “late in the game,” he persevered. Though he wasn’t fast enough to make the USA team headed for the Montreal Olympics in 1976, he met Mark Spitz at trials and was inspired to keep trying to get ready for the 1980 Olympics. But then the United States announced it would boycott the Moscow Games because of rising tensions with Russia. The Tuna would not be an Olympic swimmer.

But he wasn’t done with swimming just yet. A friend in Buffalo had suggested he swim the English Channel. He’d dabbled in open water swimming during his years in California, so he started looking for sponsors and began building his open water resumé.

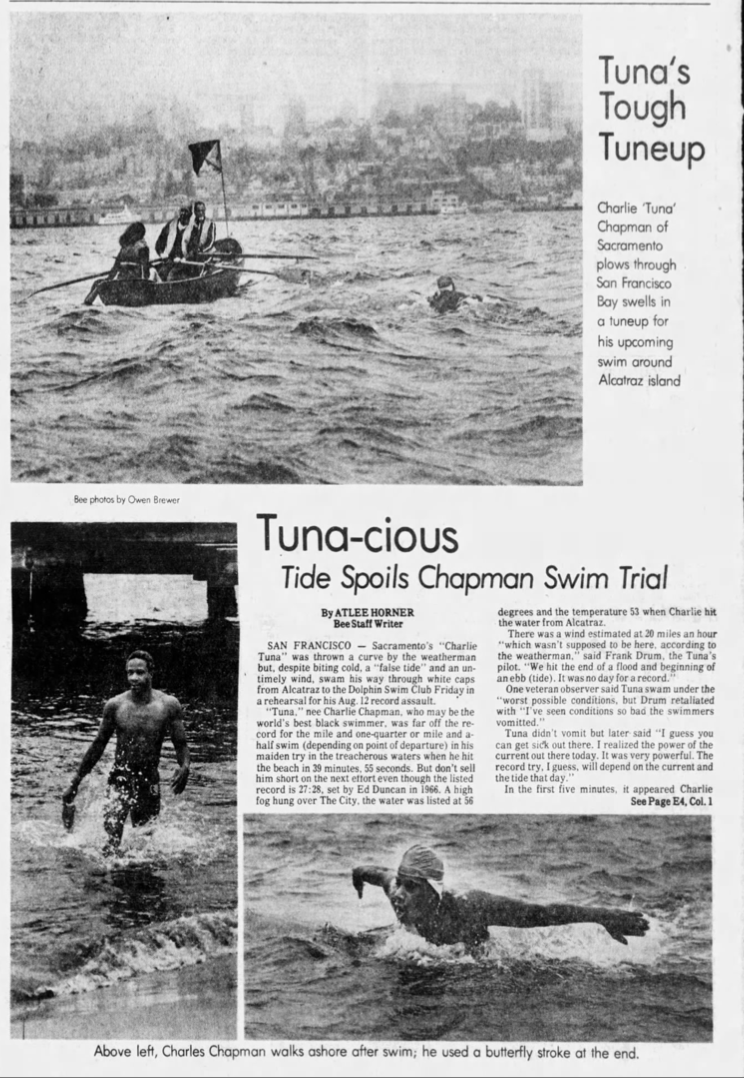

Among his more memorable swims was a speedy trek from Alcatraz Island to the mainland of San Francisco in 36 minutes, just 9 minutes shy of the record. His efforts earned some local media attention. “I was the first black guy to do it. I was front page news of the Sacramento Bee,” a newspaper based in northern California, he told Ali.

In 1978, he swam 3.5 miles out and around Alcatraz and back. He was only the third person to complete that swim, the local press reported at the time. He was heralded as “a black long-distance swimmer, one of an exceedingly rare species,” a July 1978 column in the San Francisco Examiner reported.

“I think there are only about five or six black competitive swimmers in the whole world,” Chapman was reported as saying. “One, Enith Birgitta of the Netherlands, won a bronze medal in the freestyle at the last Olympics. There’s a guy in Santa Clara, two more in Chicago, and me. That’s all I know of.”

Chapman’s fame grew as did interest in his potential for crossing the English Channel. Still, he recalled that “trying to get the money to go do the Channel was harder than swimming the Channel itself,” a statement that still rings true today in this sport that tends to favour athletes of means.

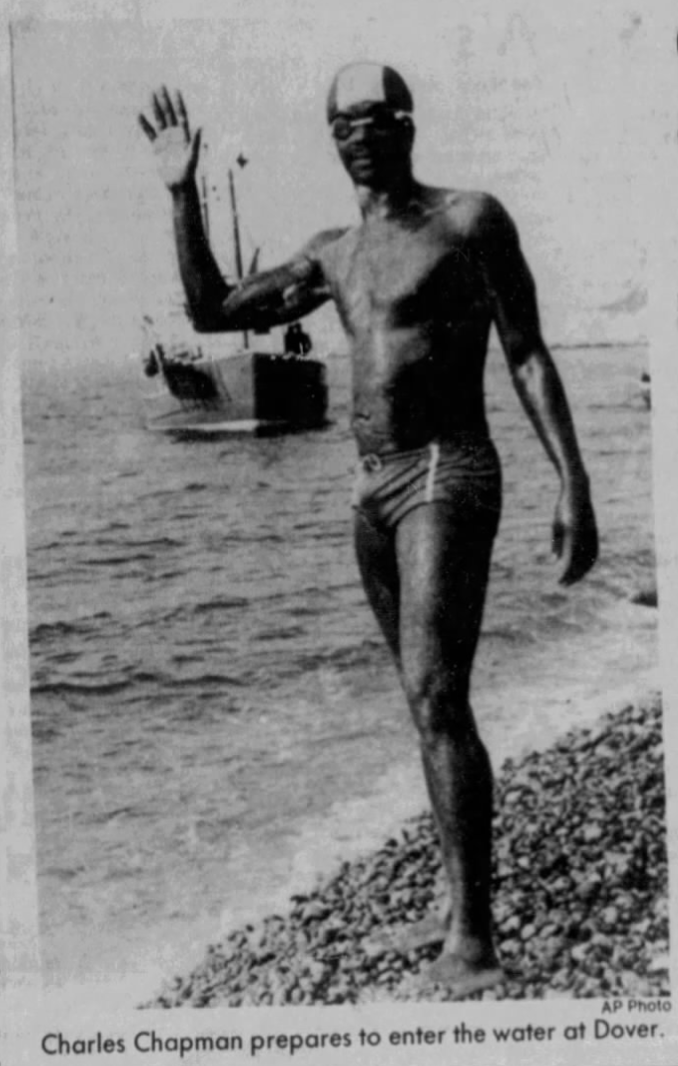

Chapman on Dover beach

Finally, Chapman’s father, who owned a haberdashery in Buffalo, organised a group of investors to help fund his son’s swim, and the planning began in earnest. Chapman upped his cold water training, swimming all winter in an unheated outdoor pool and in San Francisco Bay to build his cold tolerance.

He soon worked up to a 26-mile swim in the Sacramento River to test his readiness for the Channel’s 21-mile distance. He also completed several training swims in Lake Ontario and Lake Erie near Buffalo to help prepare for what weather challenges he might face between England and France.

On one swim his trainer Henry Clark, a former heavyweight boxer, told him to get swimming despite the bad weather. “He wouldn’t throw a fish in [those conditions] but he threw me in,” Chapman recalled, laughing.

He also completed a record-setting 13-mile swim from the South Street Seaport on Manhattan Island to Coney Island in August 1980.

But not every swim leading up to the Channel ended in victory. Shortly before he left for the UK, Chapman attempted to swim around Absecon Island, a barrier island in New Jersey where Atlantic City is located. He wasn’t able to finish that swim, and it was a stark reminder that sometimes, Mother Nature wins, despite your best laid plans.

That challenge threw doubt on his whole endeavor, but Chapman also faced disbelief from folks who couldn’t get used to the idea of a black man swimming. “There were a lot of people thinking I just wanted to go to England for a free trip and that I wasn’t going to swim the Channel,” he told Ali. But he was serious and a serious contender to become the first black American to swim the Channel.

A Fish in Water

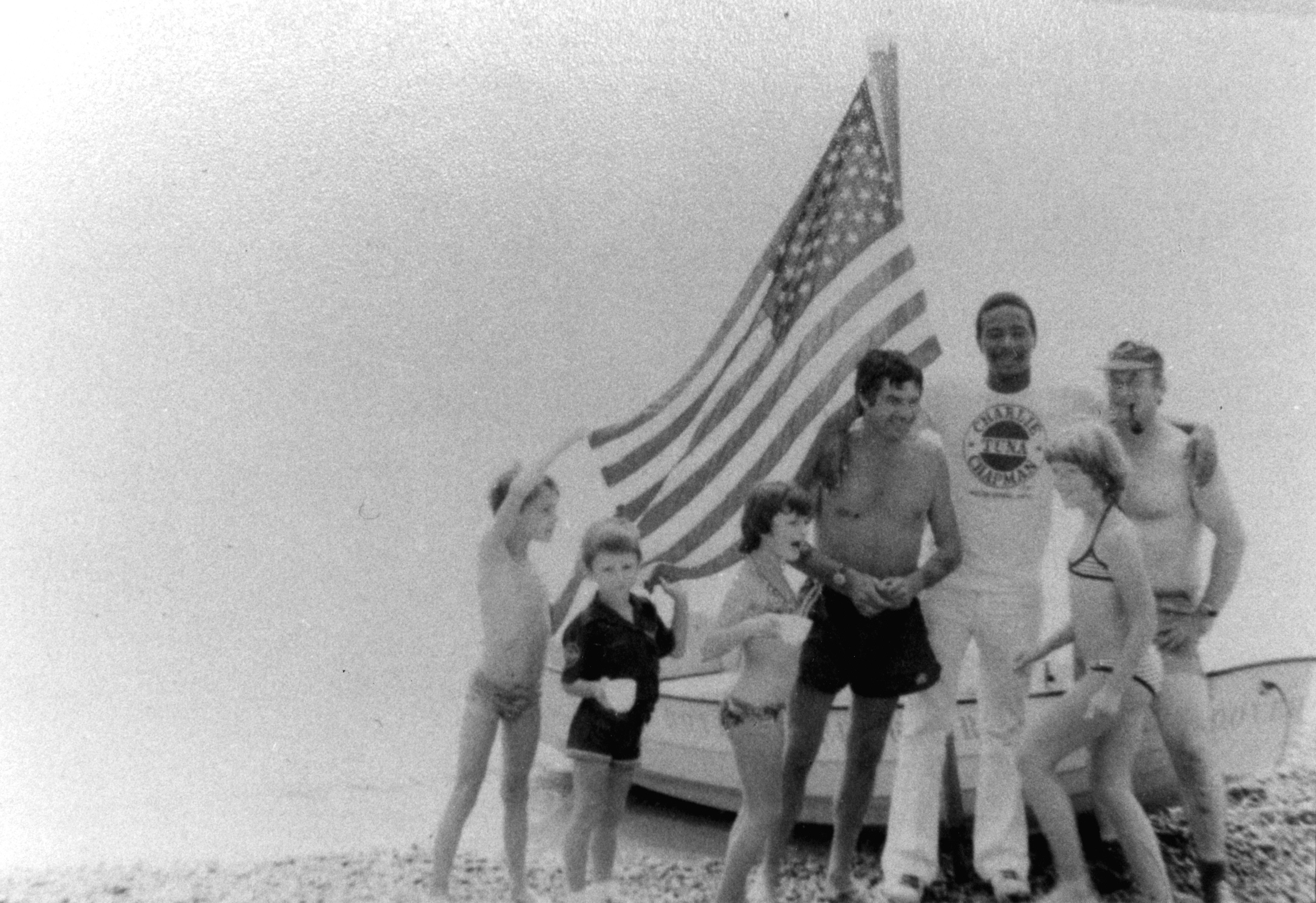

Chapman had grown so accustomed to being the only black person every place he swam that it was a bit of a shock to turn up at Swimmer’s Beach in Dover that first day in the UK and find another black American, Michael Johnson from Houston, Texas, there readying for a Channel attempt, too.

Johnson struggled with the cold and it’s unclear whether he ever made a formal solo attempt, but he did take part in a relay a few days before Chapman’s crossing. Johnson became “the first brother to swim in a relay across the Channel,” Chapman noted.

When Chapman got the call that it was finally his turn, the momentousness of what he was doing was not lost on him or his team. “My trainer told me, ‘black people have been waiting too long for this for you to fail, brother.’ It was my shot now.”

And the pressure was on, he told Ali. “Where I come from, brother, if I hadn’t made it across the Channel, I’d have been known as ‘the fish that didn’t make it’ for life!”

But he did make it, and how. Though Chapman experienced cramping in his left leg about halfway across the Channel, he persevered. History was being made in such an exciting way that everyone on board the support boat got swept up into it, including his observer, who jumped into the water about 100 yards from shore. “What’d he do that for? We had to stop and rescue this clown. He probably cost me 20 or 30 minutes,” Chapman laughed. “We found him in the dark, and they lost me for a minute. But then they found me because of my tan.”

Chapman never actually saw land prior to beaching himself on a desolate stretch of sand in France. “There was no one to greet me, but I took the mandatory 10 steps. And man, you talk about elation. I was just thrilled. I was just thrilled. I was the first to do that. It was a beautiful thing.”

Chapman at Dover

In 1988, Chapman continued his pioneering ways, becoming the first black person to complete the Manhattan Island Marathon Swim, a 45.9-kilometer loop around Manhattan Island. “It’s almost like being Jackie Robinson paving the way, except I’ll be wearing a little bathing suit,” he told the Washington Post prior to his 1988 MIMS swim. He repeated his MIMS success in 1989.

After each of his important first swimming successes, newspapers declared Chapman a hero and a victor who made a mark for black swimmers worldwide. The problem with hero worshipping sports stars is that they are still human and fallible, and Chapman’s story also includes an arrest for conspiring to sell 5 ounces of cocaine. Though he maintained he was not involved with a drug trafficking ring on the East Side of Buffalo, he was sentenced to two years and nine months in federal prison.

“He Looks Like Me”

Despite that fault, Chapman’s story of hard work and daring to be different has inspired other black swimmers over the years, including Naji Ali, a long-time member of the South End Rowing Club in San Francisco, an avid bay swimmer, and a coach who creates opportunities in aquatics for a diverse range of individuals. Ali says having that time to speak with his swimming idol was extraordinary and affirming of his own efforts in the sport.

“I’m not easily star-struck, but I’ve said that there are a few people who if they walked through the door, I’d be pretty excited,” Ali says. Meeting Chapman was like meeting Lynne Cox for the first time—awe-inspiring.

“I’d never come across another African American who had the passion for open water that I did,” and representation in what many open water swimmers see as the pinnacle of the sport – the English Channel – was powerful stuff for Ali. “He’s black. He looks like me.”

But this kind of representation has been largely lacking in the sport of swimming globally. In a videotaped interview broadcast on a local Buffalo television station shortly after Chapman’s successful Channel swim, the white, male reporter asks Chapman “why haven’t we seen more black swimmers?” It’s a question that carries a lot of weight and poignancy today, as the number of black participants in marathon swimming is still exceedingly low.

Chapman told the reporter: “I think the reason is that for so long, black people have not been exposed to swimming and they believe they’re going to drown because they have a lot of different water-related accidents and drownings. So consequently, the majority of the population is gripped in fear of water.”

Carl Richards at Tooting Bec Lido, south London

There’s More Work to Be Done

Forty years on, there are still massive barriers to participation and a yawing disparity in participation rates for black and brown people at all levels of swimming. Seeing people of color at marathon swimming events and training sessions is still the exception rather than the rule.

It seems the old myth that “blacks can’t swim,” (as Ed Accura recently explored in his documentary “A Film Called Blacks Can’t Swim”) still holds sway for many. But it’s patently untrue. Chapman proved it. Other black swimmers have also proved it again and again over the years. But that reporter’s question from the early 1980s still hangs in the air. “Why aren’t there more black swimmers?”

Lack of access, institutionalised racism, cultural norms and social expectations, socioeconomic disparities, segregationist policies, skin and hair texture differences, and a range of other factors all play a role in why black swimmers are underrepresented in aquatic sports.

Indeed, here in the United States and in much or Europe, people with brown or black skin are so infrequently present at marathon swim events that it’s remarkable when someone with more melanin does turn up for a swim.

Carl Richards, a London-based marathon swimmer who completed a crossing of the English Channel on 31 July 2009 says he’s often the only person of colour when he goes swimming. His father was African and his mother is white, and he identifies as a black man. “There have been a few times when I’ve looked around the lido and the population of the lido and it’s a very white institution. Through absolutely no fault of their own,” he hastens to add. “They’re the loveliest people, and I’ve never felt any kind of color discrimination at all. But every once in a while, I recognise it,” he says.

A sport that strips you down to just a few inches of fabric leaves a lot of skin exposed to be reckoned with, and hue becomes obvious. Bringing more people of color into the sport is an important issue that needs to be grappled with because the water shouldn’t be only for white people or those who conform to a certain standard. Diversity, inclusion, representation, and accessibility all matter, as do black lives.

And, as Charles Chapman of Buffalo, New York proved, blacks can in fact swim. Maybe even just like a fish sometimes. Though the Tuna’s truth remains a decidedly

human story.