Swimming with Raynaud’s

Reader’s frequently ask us about Raynaud’s phenomenon and swimming. Raynaud’s is a condition where the blood vessels in the extremities, particularly fingers and toes, are over-sensitive to the cold. When Raynaud’s is triggered, the fingers typically turn white (or paler, in people with dark skin), with associated pain and numbness. Later, during recovery, they can turn reddish or purple as the blood returns to the fingers, which can also be painful.

To develop a better understanding of the condition among swimmers, we carried out a survey of Outdoor Swimmer readers. More than 1,300 people responded – a clear indication of the extent of concerns about Raynaud’s in the swimming community. The two biggest worries people expressed were (1) will outdoor swimming make my symptoms worse and (2) will outdoor swimming cause permanent damage. Through the answers to the survey and additional research, we have attempted to answer those questions below. However, please remember, we are swimmers and journalists, not medical experts. Consult a specialist if you have any doubts.

Raynaud’s affects a lot of swimmers

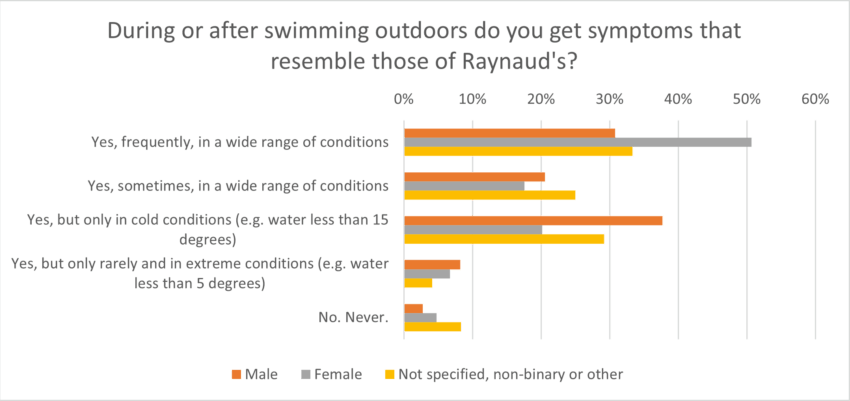

Our first question asked about Raynaud’s symptoms triggered by outdoor swimming.

More than half of women and nearly one third of men who responded to our survey experience Raynaud’s symptoms. In general, Raynaud’s affects women more than men and this was reflected in our survey: 84.3% of the responses were from women, 13.3% from men and 2.4% not specified, non-binary or other. Incidentally, the average age of respondents was 46, and the range was 14 to 75.

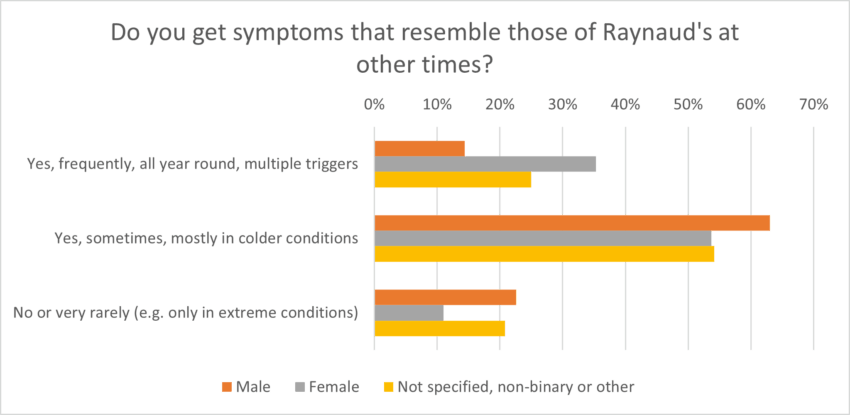

We next asked if people experience symptoms at other times. Here are the results.

The obvious question coming out of these results is: does a preponderance to Raynaud’s symptoms in general increase the likelihood that you will suffer those symptoms when swimming? The answer, according out our data at least, is yes: 75.6% of people who frequently suffer Raynaud’s symptoms year-round are also frequently affected when outdoor swimming in a wide range of conditions. A further 13.9% of this group are sometimes affected. However, a lucky 4.5% of Raynaud’s sufferers say they never get symptoms while swimming.

Only when swimming

Outdoor swimming frequently triggers Raynaud’s symptoms in 15% of people who never normally suffer from the condition, according to our survey. A further 8% of non-Raynaud’s suffers say they are sometimes affected while nearly 40% of this group experience symptoms in cold water (which we defined as 15 degrees for the survey). One in five people who never normally get Raynaud’s symptoms are affected in extreme conditions (less than 5-degree water).

For better or for worse

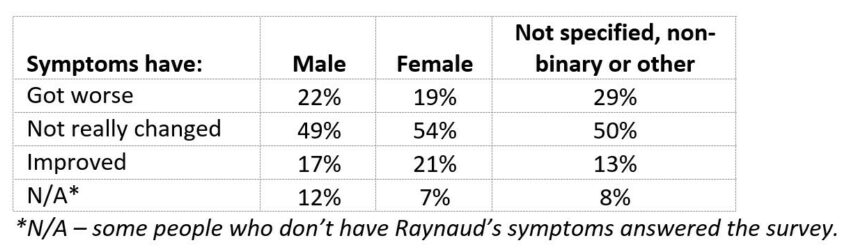

Given that outdoor swimming appears to be a trigger for Raynaud’s symptoms for both people who suffer from it generally and those who don’t, the worry is that swimming could make it worse. Here are the results from the question: “Have your Raynaud’s symptoms become better, worse or stayed about the same since you became an outdoor swimmer?”

The conclusion we draw from this is that the long-term response is individual. For every person whose symptoms have got worse, there is someone whose symptoms have improved, while the majority noticed no change. Remember, other factors such as stress could also play a role in changing symptoms, and that these changes are self-reported, not scientifically assessed. If your symptoms do worsen, speak to a medical professional. They might not be caused by swimming.

Again, we dived deeper into the data to see if we could tease out any informative correlations. Among swimmers who suffer generally from Raynaud’s symptoms, 25% said their symptoms had improved since they became a swimmer, 15% had got worse and 57% stayed about the same. Conversely, among people who only rarely experience symptoms, 22% said they had got worse since becoming a swimmer and 10% said symptoms improved.

It’s a complex picture. But is it doing swimmers any harm? Our next question looked at the severity of the symptoms and the levels of inconvenience or pain caused. For an unfortunate 7% of our survey respondents, Raynaud’s symptoms are very painful and off-putting to swimming in cooler conditions. A further 20% find them moderately painful, prompting them to think twice about swimming in cooler conditions or taking precautions such as wearing gloves and booties. The largest group, 43%, experience some discomfort but they are not put off swimming. For 25%, it’s a minor pain-free inconvenience causing some loss of dexterity and feeling. Just 3% say it’s mainly aesthetic and not a bother and 2% of respondents said they didn’t ever get symptoms.

The picture is worse for people who frequently suffer Raynaud’s symptoms outside of swimming. In this group, 12.8% experience very painful symptoms that put them off swimming. Among those who only have occasional symptoms in daily life, 4.7% suffer painful symptoms when swimming. None of the people who are symptom free in daily life reported a high level of pain when swimming. In this latter group, symptoms were mainly a minor inconvenience (27%) or caused some discomfort but not enough to put them off swimming (38%). Overall, there is a clear correlation between the level of symptoms people have generally and those that are triggered by outdoor swimming.

Managing symptoms

The most popular method for managing symptoms among survey respondents is to use neoprene socks or booties when the temperature drops. Around 40% of people do this, while 20% say they use them in all open water conditions. The next most popular measure, at 36%, is to use neoprene gloves in cold water, with 17% using them in all conditions. Some people (13%) simply stop swimming outdoors below a certain temperature. A small portion (2%) use medication to manage their condition. One in four don’t use any of the above methods to manage their symptoms. Note, percentages don’t add up to 100 as some people use multiple methods (e.g. both booties and gloves, and avoiding very low temperatures).

In their free text answers, people mentioned things such as windmilling or shaking their arms to promote blood flow, using hand warmers and heated insoles, and always keeping gloves in their pockets – even in summer – in case they are needed. Other people recommend heating your clothes while swimming (e.g. leaving them wrapped around a hot water bottle) and getting inside, away from any cold drafts, as quickly as possible after swimming.

Interestingly, while most people find that neoprene gloves help, several respondents said they can make things worse due to the time taken to remove them after swimming and the additional faff factor. It’s worth experimenting to see what works for you.

See below for a longer list of measures that individuals experiment with to manage symptoms.

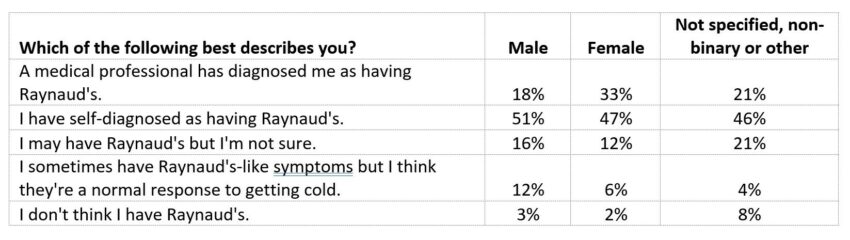

Diagnosed

Out next question asked about respondents’ diagnostic status regarding Raynaud’s. A significant proportion have been diagnosed by a medical professional as having Raynaud’s, with women being diagnosed just under twice as often as men. The majority of respondents have self diagnosed. See the full results in the table below.

Should you see your doctor?

The NHS advises you see your GP about Raynaud’s if:

- your symptoms are very bad or getting worse.

- Raynaud’s is affecting your daily life.

- your symptoms are only on 1 side of your body.

- you also have joint pain, skin rashes or muscle weakness.

- you’re over 30 and get symptoms of Raynaud’s for the first time.

For most people who have symptoms, Raynaud’s is a nuisance that you need to manage and live with, and doesn’t cause any long-term harm. However, in a minority of cases, it could be a sign of a more serious condition. You should speak to your doctor if you have any concerns.

Non-freezing cold injury, chilblains and frostbite

Non-freezing cold injury is a poorly understood condition that can cause long-term or in severe cases permanent damage to affected body parts, usually the feet and hands. Frostbite occurs if body tissue freezes which occurs at about -0.5°C. The risk of both these conditions probably increases for people with poor circulation. Therefore, if you have, or think you have, Raynaud’s, take extra care in cold conditions. Also note that initial symptoms for non-freezing cold injury look similar to Raynaud’s. However, Raynaud’s symptoms should disappear shortly after swimming and not result in any long-term pain or numbness.

Another risk for cold water swimmers is chilblains, a mild form of non-freezing cold injury, which some people suffer from after getting cold. A question for a future survey should be to investigate if there is any correlation between susceptibility to chilblains and Raynaud’s. NHS advice for reducing the risk of chilblains is to not put your hands on a hot radiator or under hot water to warm them up.

One of the biggest worries among survey respondents was the risk of causing long-term or permanent damage through swimming. For most people, this seems unlikely, provided you take measures to minimise symptoms before, during and after swimming. However, if you experience any pain, tingling or numbness that continues post swimming, this may be a sign of non-freezing cold injury. If this is a worry for you, take additional protective measures and seek professional medical advice.

Swimming with Raynaud’s

Most people we surveyed – 79.1% of them – have never considered given up swimming in cold water because of Raynaud’s. They enjoy it too much. Another 14.6% have thought about it, but continued swimming anyway, leaving 3.2% who have given up swimming in cold water and 3.1% who never swam in cold water anyway. For the vast majority, therefore, while Raynaud’s is an issue, it does not stop them swimming.

But, the picture changes, as you would expect, with the severity of symptoms. Only two respondents (out of 1300) whose symptoms were minor or cause some discomfort have given up swimming in cold water. Among those who describe their symptoms as ‘moderately painful’, 6% have given up swimming in cold water and 33% have thought about it. And for people with ‘very painful’ symptoms, 26% have given up cold water swimming and 41% have thought about it. Yet even within this group, more than 1 in 4 say they enjoy swimming in cold water too much to give up, despite the pain it sometimes causes them!

It is almost inevitable that you will occasionally get cold if you’re an outdoor swimmer. That is not necessarily a bad thing and there is widespread anecdotal support for the idea that safe cold exposure will do us good. Raynaud’s adds a complication. Mostly it’s an inconvenience but, for a small number of people, it is a painful and debilitating condition that limits their swimming. If that’s the case for you, we recommend speaking to your doctor.

Tips from survey respondents on managing Raynaud’s (abridged to remove duplicate or similar suggestions)

- Heat up your clothes so they are warm when you put them on.

- Warm up your gloves in the microwave.

- Swing your arms in circles to push blood to the fingertips or shake hands vigorously.

- Have hot water bottles and hand warmers ready for after your swim.

- Swim for less time to avoid getting too cold.

- Get warm and dry quickly after swimming, and then eat.

- Once dressed, hold a hot water bottle against your tummy or between your thighs (but not directly against the skin).

- Lots of layers for after swimming, including windproof layers.

- Sit indoors in a sunbeam and soak up the warmth like a cat.

- Consume raw ginger, in tea or juiced.

- Get special Raynaud’s silver gloves.

- Wait until all Raynaud’s symptoms have gone before showering.

- Wear a rash vest under your wetsuit for extra warmth.

- Turmeric paste daily (eaten, presumably!).

- Drink warm water instead of cold during the day.

- Desensitise the hands by submerging them daily in ice water (take care not to give yourself a non-freezing cold injury if you try this).

- Drink something warm before your swim.

- Wear wrist warmers made from old socks.

- Get warm before swimming with extra layers and movement.

- Warm the hands up slowly to reduce pain.

- Swear.

- Stand on a mat when changing to keep feet insulated from the ground.

- Go for a brisk walk once dressed.

- Reduce caffeine, exercise regularly, follow an anti-inflammatory diet.

- Massage hands and fingers after swimming.

- Wim Hof breathing exercises.

- Take various supplements including multi-vitamins, B-vitamins, magnesium, cinnamon, cayenne and ginkgo biloba.

- Double socks and gloves.

- Clapping.

Images thanks to Helen Davis