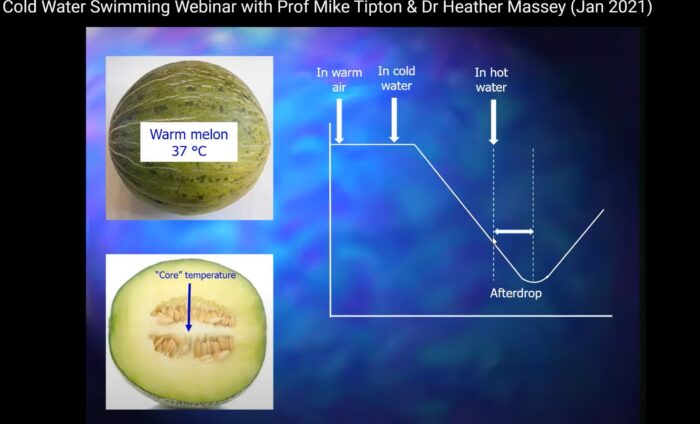

Even melons get “after-drop”

Even melons get “after-drop” and this proves that it’s not caused by cold blood returning to your core.

When you swim, your body loses heat to the water. If that rate of loss is faster than you can generate heat through metabolic processes, then you will cool down. If you measure your deep core temperature with a rectal thermometer (please note, this is something best done in the controlled conditions of a laboratory), you will observe that your temperature continues to drop, at roughly the same rate, for about 20 to 30 minutes after you exit the water. This is known as “afterdrop”.

A common misconception – and I was guilty of this – is that after-drop happens when cold blood from peripheral areas returns to your core. That is certainly a plausible theory and one that’s easy to grasp, intuitively. But it’s incorrect.

Immerse Hebrides, a company that organises guided wild swims in Scotland, and H2O Training, which provides instructor training, hosted a webinar in January with Professor Mike Tipton and Dr Heather Massey, who work at the Extreme Environments Laboratory in Portsmouth University, and are experts on the dangers and benefits of cold water swimming. If you didn’t manage to see the original webinar, it’s available on YouTube (see link below) and well worth watching. In it, Professor Tipton describes the melon experiment, which he urges you to try at home. You need a melon, a means to warm it in air to 37 degrees Celsius, a water bucket and a probe thermometer. Allow the melon time to warm up completely to 37 degrees then plunge it into cold water for about 15 minutes and measure its core temperature every minute. Be careful to ensure cold water doesn’t penetrate to the melon’s core. Once you can see that the core temperature is falling, remove the melon from the water and put it in a warm bath. What you should observe is that the temperature at the centre of the melon continues to drop, at the same rate, for a period of time after you remove it from the cold, before stabilising and then recovering – exactly the same as observed in people. The point is, melons don’t have circulating blood, which means the afterdrop is a conduction phenomenon, not a convection one.

For most practical purposes, this shouldn’t make any difference to swimmers. It is still a good idea to dress quickly after swimming and try to keep out of the wind. There was an idea that you should cover the core but leave the limbs exposed, to discourage cold blood flowing back to the core, but this is not necessary. Just get dressed. As for re-warming your extremities, well it seems as if you have to wait until your core has re-warmed through conduction. Warm blood will then start to recirculate to your fingers and toes.

The webinar answers lots of other questions you might have about cold water swimming, such as does it make a difference if you exercise and heat up in advance, should you exercise afterwards and what is SIPE. I recommend it.