How to stay hydrated while swimming

We spoke to Andy Blow, co-founder of Precision Fuel & Hydration and former elite triathlete, about the hydration needs of outdoor swimmers. Andy is a sports scientist and an expert in sweat, dehydration and cramping.

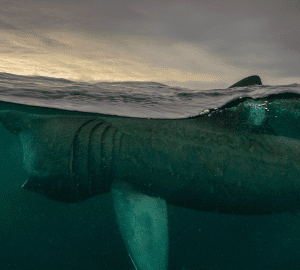

As swimmers who spend lots time in water, you might not think hydration would be an issue. But that is not the case. The picture is complicated for swimmers. We swim in both fresh and salty water with a wide range of temperatures. Sometimes we swim with wetsuits and other times without. Being in cold water causes changes in our blood flow and concentration and makes us pee more, and some swimmers stay in the water for many hours or even days. We also know less about swimmers and sweating than we do for land-based athletes because of difficulties in measuring sweat rates and concentrations (some people lose a lot more salt in their sweat than others). Given that, we knew we wouldn’t get simple answers to our questions for Andy Blow of Precision Fuel & Hydration, but we learned a lot.

What should swimmers think about, in terms of hydration, for swimming events of between around 20 and 60 minutes?

For shorter events like this you will perform best – and probably have a more enjoyable swim – if you arrive on the start line properly hydrated and fuelled. However, this is easier said than done, and it’s easy to be over-zealous. On the day before your event, maybe drink an extra bottle (500ml) of water than you normally would, but don’t drink and drink as this can lead to a potentially dangerous condition known as hyponatraemia. This occurs when the electrolyte concentration in your body’s cells becomes too low for them to function properly. Also moderately increase your carbohydrate intake on the day before your swim.

If the conditions are warm or you’re wearing a wetsuit that will increase your sweat rate, consider ‘pre-loading’ for your hydration 60 to 90 minutes before your swim with a strong electrolyte drink such as PH 1500. The additional sodium helps pull water into your blood stream.

In most circumstances, you will not need to eat or drink anything during events of up to one hour.

How do things change if you expect your swim to take between one and two hours?

The basic principle of arriving fuelled and hydrated at the start of you swim is the same whatever the distance. For swims of between one and two hours, you may find pre-loading as described above useful, especially towards the latter end of the swim.

We normally consider 90 minutes of high intensity exercise to be the approximate point when your muscles run low on glycogen. Given the trade-offs in lost time and possibly losing your place in the pack, I wouldn’t bother taking anything for a swim of less than 90 minutes.

However, if you’re approaching this limit, you may want to prioritise nutrition over hydration, especially as there are practical difficulties in carrying water while swimming. You can easily pack a gel inside your costume or sleeve of your wetsuit. I’d go for one of the thinner, less sticky or isotonic gels, which are more palatable if you don’t have water. It takes about 15 minutes for the carbohydrates to reach your muscles, so factor this in and maybe take the gel after about an hour of swimming.

What do you need to consider for longer swims?

Swimming presents different challenges to nutrition and hydration than land-based sports, such as running and cycling.

With the latter, you can eat or drink with barely any impact on your speed. With swimming, you need to stop. This could cost you places in a race and while your overall time might not be important on a long solo swim, you may get cold or carried by the currents if you stop for too long. I suspect (but I don’t know) that in elite-level marathon swimming, the athletes do not fuel or hydrate optimally from a nutrition perspective as the best racing strategy is to stay with the pack.

It’s hard to give precise guidance because of individual variation and the huge range of conditions that people swim in but it’s worth considering the following factors:

- On longer swims, especially in cool conditions, the priority will be calories rather than fluids, so focus on those.

- If you are mixing drinks from powder, trial increasing the concentration above the recommended so you can get more calories in with less liquid volume, especially in cold conditions.

- Your opportunities to practise under event day conditions will be limited but try to replicate what you can and use the same hydration and nutrition. For example, in a pool training session, rather than sipping your drink every few lengths, try waiting 30 minutes and then drinking a larger quantity.

- Make sure you are properly fuelled and hydrated for your training sessions, especially the longer and harder ones, to get the most out of them.

Do you need to change your hydration strategy or products when swimming in salt water?

There is the idea that you don’t need electrolytes in your drinks when swimming in salt water because you will almost certainly inadvertently swallow some of the water you’re swimming in. This is plausible, and sea water is something like 10 times as concentrated as even the strongest electrolyte drink. However, it’s something that would be hard to quantify.

As mentioned above, due to practical considerations when swimming, I would ensure I started the event properly hydrated and then focus primarily on nutrition rather than hydration anyway. Note that in my experience, energy gels can taste quite different (and much worse) after you’ve been swimming for a while. Test what works best for you. I prefer the lighter, less-sticky options for sea swimming.

What would you change for warmer and colder conditions?

On land, we use the rough rule of thumb that you need about 500ml of fluid per hour. Obviously, this varies between individuals and with conditions. You might, for example, double this if training or racing in the heat.

While swimming outdoors you probably need less, unless you’re wearing a wetsuit, in warm water. I would use powdered drinks and vary the concentration according to the temperature – more dilute in warm conditions and more concentrated in the cold. If it’s an option, warm (but not hot) drinks can be a good idea in cold water.

What advice do you have for people who are swimming for their health and wellbeing rather than fitness and competition?

Whatever your motivations for swimming, I believe you get the most out of each swim by being properly hydrated and fuelled before you start, and replenishing what you’ve lost after. For low intensity swims, this shouldn’t require anything other than paying attention to what you eat and drink throughout the day. Just have a reasonable amount of water and ensure you include carbohydrates in your food as that’s what your muscles need to work.

I don’t think you need any complex guidelines: just be organised. Also bear in mind that if you get cold and start to shiver, your muscles need carbohydrates for that. As shivering is an important part of the rewarming process, it’s important to have fuel. Hot sweet drinks will help.

What are signs you might have something wrong with your hydration or nutrition?

Generally, our bodies tell us what we need – if you have a dry mouth you probably need a drink – so listen to your body’s cravings. However, it can be harder to tune into what your body needs in some conditions, such was swimming in salty water. Being bloated or needing to pee a lot could be an indication that you’ve drunk too much, but being in cold water also increases the amount you pee so this isn’t a reliable indicator. Getting cramp could be a sign of dehydration.

When it comes to energy, I follow the advice of ‘low mood, go for food’. For example, if in the middle of a long race, my attitude changes and I stop wanting to be there, it’s often because I need to eat. A craving for sugary things is also a good indicator that energy is running low.

Typically, athletes (not just swimmers) pay a lot of attention to their training, but much less to their hydration and nutrition. Because training is such a repetitive activity, it has lots of scope to experiment and make small changes.

Keep a log of what you eat and drink and how you feel while exercising. There isn’t a right answer for everyone and the window for what works is wide. At the same time, there’s lots of scope to get things very wrong. Build your own database of what works for you and what doesn’t. Nothing beats your own experiences.

Click here for more information about nutrition and hydration for swimming